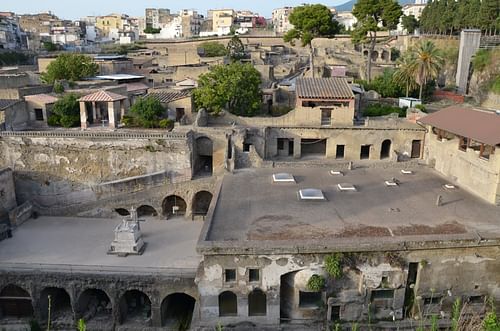

In the first part of our new travel series devoted to the archaeological sites around the Bay of Naples, we shared some hints and tips as to how you can best prepare for your self-guided tour of Pompeii. In this second part, we look into the fascinating history of Pompeii's "little sister", the town of Herculaneum. Located just 17 kilometres (10 miles) to the north of its more famous neighbour, the archaeological site attracts fewer tourists, but the exceptional preservation of this Roman seaside town and the compactness of its exposed remains might even offer the visitor a more satisfying experience than Pompeii.

In Herculaneum, there are two-storey buildings, wooden furniture, traces of wooden stairways and balconies, luxurious patrician villas and even merchant shops with their original wooden shelves holding amphorae. Its destruction and preservation have made Herculaneum an extraordinary place which genuinely deserves the same renown as its famous neighbour.

A Roman Seaside Resort

Herculaneum was a small walled town located a short distance from the sea, west of Mount Vesuvius. As its name suggests, it was originally dedicated to the Greek god Herakles, who, according to the legend told by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (60 BCE), founded the city after his return from one of his twelve labours. The precise early history of Herculaneum is unclear, but the urban planning suggests that it may have been connected with the Greek colony settlements in the Naples area. According to Strabo (ca. 64 BCE - 24 CE), the city was subsequently inhabited by Oscans, then Etruscans and Pelasgians, and finally by Samnites in the 4th century BCE. The town remained a member of the Samnite league until it became a Roman municipium in 89 BCE during the Social War.

Herculaneum was then transformed into a purely Roman town and prospered as a quiet, secluded seaside resort for wealthy and distinguished Roman citizens who built beachfront residences with panoramic sea views. Unlike Pompeii, which was mostly a commercial city with ca. 12,000 inhabitants, Herculaneum was relatively modest in size. The overall surface enclosed by the walls was approximately 20 hectares (one-quarter of Pompeii), for a population of roughly 4,000 inhabitants. However small, the city is remarkable in terms of its evident wealth. The city had a richer artistic life than Pompeii and had more elaborate private buildings. Many houses of Herculaneum had two or three stories with atria and peristyles and were decorated with finely executed paintings and expensive furnishings.

The Death of Herculaneum

Herculaneum suffered severe damage in the earthquake of 62 CE, and soon after that, like its neighbour Pompeii, was a victim of the Vesuvian eruption of 79 CE. However, the circumstances of the burials of the two cities were very different. As the wind on this fatal day was blowing in the direction of Pompeii, it carried the ash cloud away from Herculaneum which received only a light dusting of pumice stones, minimising the damage to the town's infrastructures. Eventually, however, Herculaneum succumbed to the series of thick pyroclastic waves that thundered down the mountainside and extinguished all life in the city. The temperature of the surge was so intense (nearly 450°C/840°F) that organic materials, such as wood furniture cloth, food, and rolls of papyrus that otherwise perished or burned at Pompeii, instantly carbonised and were discovered remarkably well preserved. The town ended up buried under 20 metres (almost 50 foot) of volcanic material, much more than the 5 metres (16 feet) of ash at Pompeii. As a result, Herculaneum is an ancient town whose ruins are better preserved than those in Pompeii and has different stories to tell.

The Rediscovery

Herculaneum was the first of the Vesuvian sites to be rediscovered in 1709 CE when a well-digger stumbled upon the theatre. Soon statues, columns, inscriptions, and bronzes were brought to the surface by tunnelling through the hardened ash. Full-scale excavations began in 1738 CE under the auspices of Charles of Bourbon, the King of Naples, and on December 11 of the same year, an inscription that reads "Theatrum Herculanensi" came to light. The Roman town of Herculaneum was rediscovered. Further tunnelling resulted in exposing more of the buried city and to the north of it, diggers came across the sumptuous Villa of the Papyri, one of the largest and most beautiful private houses in all antiquity. In the villa, some 1800 scrolls were discovered as well as 90 bronze and marble sculptures that can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. Amateur excavations were carried out intermittently until 1875 CE but only revolved around collecting valuable artefacts and antiquities. Systematic excavation work began again in 1927 CE when teams supervised by Amedeo Maiuri ( 1886 – 1963 CE), one of Italy's pre-eminent archaeologists, managed to unearth one-quarter of the town's original area.

Since 2001 CE, the Herculaneum Conservation Project, a joint project led by the Packard Humanities Institute, the British School at Rome, and the Superintendency for the Archaeological Heritage of Naples and Pompeii, has worked to halt the severe decay conditions and save the site. Although two-thirds of Herculaneum remains unexplored, with the forum complex yet to be excavated, the continuous care of the site has resulted in new archaeological discoveries as well as the recent reopenings of the ancient theatre and the House of the Bicentenary. Besides, new techniques may soon enable the hundreds of carbonised papyrus scrolls to be read once more.

Practical Information

Herculaneum is an easy trip from Naples or Sorrento. The local train service around Vesuvius is the Circumvesuviana Line that runs between Naples and Sorrento and has stops near all the major archaeological parks. Exit the Ercolano Scavi station and walk directly downhill on Via IV Novembre for about 5 minutes to the site entrance. By car, use the Ercolano exit from the A3 Autostrada.

A single ticket to get into the Herculaneum excavations at the time of writing costs €13. It is valid for one day. A combined ticket costing €16 includes the entrance to the archaeological area and an underground visit to the Ancient Theatre of Herculaneum. However, the guided tours of the theatre are only available on Sundays at 10:00 (in English), 11:00 (in Italian) and 12:00 (in English) so it is suggested to purchase your ticket online here to ensure access. The cumulative ticket allows one entrance to the Ancient Theatre and one entrance to the Archaeological Park of Herculaneum within a week. When buying your ticket at the Park ticket office, pick up a map and the small pocket guide to the sites. You can also download your PDF guides in advance of your trip (see here).

Two passes also exist, the Herculaneum Vesuvius Card (official site) and the Campania Arte Card (official site). The Herculaneum Vesuvius Card is a three-day pass at the price of €16 that allows visitors to discover all the cultural and natural assets of Ercolano. The Card includes one entry to each of the following sites: Archaeological Park of Herculaneum, Virtual Archaeological Museum of Herculaneum, Villa Campolieto, Great Cone of Vesuvius.

Visiting Herculaneum

As opposed to Pompeii, it is possible to visit all of Herculaneum in just a few hours. We suggest spending at least 2-3 hours exploring the site. There is also a museum (www.museomav.com) located on via IV Novembre, offering virtual reconstructions of Herculaneum and Pompeii, with a bookshop and exhibition spaces. Another museum, known as the Antiquarium, is located a few steps away from the archaeological park and is hosting a permanent exhibition (SplendOri: Luxury in the Ornaments of Herculaneum) of jewellery and other precious objects from the site.

Herculaneum is much easier to explore than Pompeii due to the smaller size and its straightforward layout, covering a small grid of numbered streets. The site is divided into three parallel streets running north-south (Cardo III, IV, and V) which have upper and lower segments (superiore and inferiore). These are intersected by two main streets running east-west and called the Decumano Inferiore and the Decumano Massimo. For the visitor to the site, the long entrance pathway curving over the southern end of the site offers fine views of the Roman town with Mt. Vesuvius lying in the background. From here one can look directly across the seafront houses and in particular the House of the Deer whose owners had developed gardens, terraces, and porticoes to take full advantage of Herculaneum's panoramic sea view.

Looking directly below the houses, are twelve vaulted rooms which once opened onto the beach. They may have served as boat sheds, but these rooms became the final resting place of hundreds of residents of Herculaneum. It was here that the skeletons of approximately 300 people were found, along with some of their valuables. Trying to escape from the horrible destruction of their town, they were killed instantly by the intense heat of the eruption.

Further to the right, a newly installed footbridge brings you directly on to Cardo III, one of the main north-south streets. On the left is the House of Argus with its porticoed garden opening onto a triclicium (dining room) and other residential rooms. This noble house was originally entered from Cardo II (yet to be unearthed). Across Cardo III on the left is the House of the Skeleton. This modest house derives its name from the discovery of a human skeleton in a room in 1831 CE. It features a nymphaeum consisting of two rectangular basins with a decorative rear wall in inlaid limestone. Above the nymphaeum is a decorative frieze composed of seven panels, of which only three originals remain.

At the north-western corner of Cardo III Superiore lies the so-called College of the Augustales whose interiors were richly decorated with wall-paintings featuring well known mythological figures. The building has often been associated with the presence of the imperial cult in Herculaneum, but it might just as well be a meeting place for the town council, the local Curia or Senate House. The interior is composed of one large room with a small shrine (sacellum) decorated entirely with 'fourth style' frescoes. The left wall has Hercules standing next to Juno and Minerva, and the other one shows Hercules and Achelous, the god of all water and the rivers of the world, kidnapping Deianira. A marble inscription now placed on the wall records that two brothers, Aulus Lucius Proculus and Aulus Lucius Iulianus, gave a dinner to the decuriones and the augustales on the occasion of a dedication of a statue or an altar to the divine Augustus.

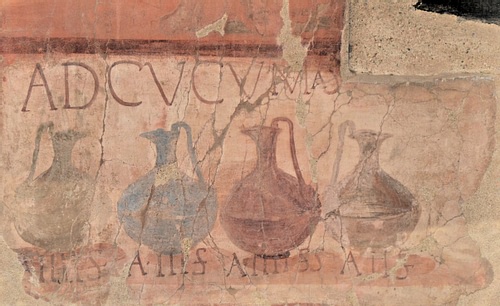

The decumanus maximus (Decumano Massimo) runs immediately to the right of the so-called College of the Augustales. The town's main east-west street was lined with shops, including one called Ad Cucumas. Look for the wall painting advertising the drinks sold there. It shows four wine jugs of different colours, each labelled with a different price per weight.

Lucky visitors will now have the opportunity to visit the House of the Bicentenary which had been closed to the public for restoration and repair since 1983 CE. The 600-square-metre (6,400-square-feet) property is perhaps the most beautiful noble house so far excavated in Herculaneum, with stunning mosaics and priceless wall paintings with mythological scenes. Located on the decumanus maximus between shops, this three-story house belonged to Gaius Petronius Stephanus and his wife Calatonia Themis.

Turning back towards the Ad Cucumas shop, the next street to the left brings the visitors to Cardo IV which contains many of the most visited houses. The first is the House of the Black Hall, one of Herculaneum's most luxurious mansions. The house has a monumental entrance which still retains the carbonised remains of its frame and architrave. The house follows the sequence vestibule, atrium, tablinum, peristyle. Some of its rooms are painted in a sophisticated 'fourth style' consisting of black central panels with architectural motifs.

On the other side of Cardo IV Superiore is the House of the Beautiful Courtyard with its interior courtyard and stairway to an upper floor. The adjacent House of Neptune and Amphitrite draws the visitor's attention due to the lavish decoration of its summer triclinium (open-air dining area) which gives the house its modern name. Adorning the east wall of the room is a mosaic showing the god Neptune and his sea-nymph wife Amphitrite. The triclinium also features a nymphaeum covered with a glass paste mosaic and shells.

At the bottom corner of Cardo IV Superiore is the Samnite House, one of the oldest dwellings in the town, dating from the 2nd century BCE. Some of its original frescoes are in the 'first style', imitating polychrome marble. Here the visitor should raise his eyes to the remarkable gallery with Ionic columns and latticework fences made of stucco on three sides.

Directly on the other side are the Central Baths which occupy the complete width of the block between Cardo III and Cardo IV. They were laid out around the beginning of the 1st century CE and were divided into separate (larger) men's and (smaller) women facilities, each with their sequence of changing room (apodyterium), warm room (tepidarium) and hot room (caldarium). The baths were decorated with 'fourth style' frescoes, had fine stuccoed ceilings while the floors were paved with elegant marine mosaics.

A little further downhill on Cardo IV Inferiore is the House of the Wooden Screen, famous for its wonderfully well-preserved wooden partition, separating the atrium from the tablinum (reception room). The adjacent Trellis House has been restored to highlight its timber-framed facade and balcony which consisted of vertical and horizontal wooden panels filled with concrete and rubble. The technique was called opus craticium and was a low-cost one considered not to be very solid and easily subject to fire. The house contained perfectly preserved carbonised furniture, including beds and cupboards.

Near the bottom end of Cardo IV is the House of the Mosaic Atrium with its exquisite geometric black-and-white mosaic decorating the whole floor of the atrium. Unfortunately, the house is currently closed, but the atrium is visible from the street.

The eastern end of the site is almost completely taken up by the partially excavated Palaestra, a spacious gymnasium and exercise area, entered from Cardo V through a large vestibule. Built during the Augustan period (27 BCE - 14 CE), this gigantic building complex was surrounded by a portico of fluted Corinthian columns on three sides and a cryptoporticus on the north side to support the terrace above. Several stores, built against the monumental edifice, supplied the needs of the public who frequented the Palaestra, including a bakery (pistrinum). Walking downhill towards Cardo V Inferiore at the junction with the Decumano Inferiore are the remains of a thermopolium (cook-shop) that sold food and drink.

Further downhill, near the seafront, is an imposing noble house. Constructed around a central courtyard, the two-storey House of the Deer contains beautiful 'fourth style' paintings with still-lifes and various architectural landscapes. The terrace garden which commanded magnificent views over the Bay of Naples has copies of two marble groups of deer attacked by dogs, the originals of which were found in the garden. Archaeologists believe that the wealthy merchant Q. Granius Verus owned the house since his stamp was discovered on a loaf of bread unearthed in the house and amazingly preserved by the volcanic ash.

On the other side of the same street is the House of the Relief of Telephus, one of the largest houses in Herculaneum covering about 1,800 sq. m (20,000 sq. feet). Its atrium is in the 'third style' with yellow panels and is fitted up with copies of marble discs called oscilla, suspended between the columns.

Lying immediately south of the House of the Relief of Telephus is the Suburban District, the ancient waterfront area. It is reached via the Marina Gate at the southern end of Cardo V and accessed by a narrow ramp. The central feature of the Suburban District is the Terrace of Marcus Nonius Balbus, the town's most prominent figure during the Augustan period. A funerary altar was erected here on the spot where his body was cremated. A cuirassed statue of Balbus was placed on the marble base behind the altar by his freedman Marcus Nonius Volusianus. A native of Nuceria, Balbus was praetor (magistrate) and governor of the provinces of Crete and Cyrenaica under Augustus. During his lifetime, he embellished the town with civic monuments and public facilities. His generosity to Herculaneum is preserved in inscriptions, and at least ten statues of him were erected in his honour.

To the east of the terrace lie the Suburban Baths, one of the best-preserved Roman bath complexes in existence, with mosaic and marble floors, stuccoed walls, ceiling decoration, and statues. Unfortunately, the building is rarely accessible to visitors. To the west of the terrace is the Sacred Area which incorporates two shrines, the first dedicated to Venus, the second dedicated to the three gods Vulcan, Neptune, Mercury and the goddess Minerva as evidenced by the reliefs.

Do not miss the opportunity to visit the ancient theatre of Herculaneum, located outside of the archaeological park along Corso Resina. The monument is still accessible today through a series of tunnels made in the Bourbon age, going down 20 metres below the volcanic material. Two staircases lead to a corridor whose walls are covered by graffiti left over the centuries by visitors. The theatre was built of stone in the Augustan period and could hold about 2500 spectators. It was decorated with many types of marble, large bronze statues and equestrian statues which are now at the Naples Archaeological Museum. Herculaneum's underground theatre is opened every Sunday morning with three public tours for groups of 10 people maximum.

Before visiting Herculaneum, be sure to watch the excellent BBC documentary The Other Pompeii: Life and Death in Herculaneum presented by Prof. Andrew Wallace-Hadrill, who has been heading the Herculaneum Conservation Project. Wallace-Hadrill's 2011 book Herculaneum: Past and Future also offers a fresh overview of Herculaneum's urban history and development.