The Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE) was a dynastic conflict where the nobility and monarchs of England intermittently battled for supremacy over a period of four decades. Besides the obvious consequences of Lancastrian and Yorkist kings swapping thrones several times and the establishment of the House of Tudor at the end of it all, the wars killed half the lords of the 60 noble families of England, established a much more violent political environment, and saw first a boost to the power of the nobility and then a swing back in the favour of the Crown. Finally, the wars have inspired historians and writers forever after, whether it be Tudor propagandists, William Shakespeare, or the creators of such television shows as Game of Thrones.

A Dynastic Conflict

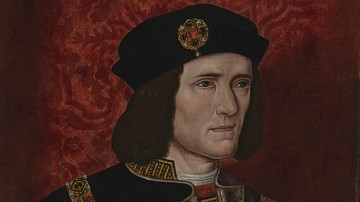

The Wars of the Roses was a series of dynastic conflicts between the monarchy and the nobility of England in the second half of the 15th century CE. The 'wars' were really a series of intermittent, often small-scale battles, executions, murders, and failed plots as the political class of England fractured into two groups which formed around two branches of Edward III of England's descendants (r. 1327-1377 CE): the Yorks and Lancasters. Although there were several reasons why the wars continued over four decades, the main causes for the initial outbreak were the incompetent rule and episodes of insanity of the Lancastrian king Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE) and the ambition of Richard, Duke of York (1411-1460 CE), then his son Edward (b. 1442 CE) who became Edward IV of England (1461-70 & 1471-83 CE), and then Edward's brother Richard who reigned as Richard III of England (r. 1483-85 CE). There were additional reasons why the wars rumbled on such as the ceaseless rivalry for wealth amongst the nobility, disagreements over relations with France, the impoverished economy, and finally, the ambition of Henry Tudor (b. 1457 CE), who finally won the war for the Lancasters and became Henry VII of England (r. 1485-1509 CE).

The various consequences of the Wars of the Roses may be summarised as:

- an increase in the power of nobles compared to the Crown during the wars.

- an increase in the use of violence and assassination as political tools.

- the destruction of half the nobility of England.

- the reassertion of the Crown's superiority over the nobility by the war's victor Henry VII.

- the creation of the House of Tudor by Henry VII.

- a continued inspiration for later writers such as William Shakespeare.

A Fragmented Kingdom

The instability caused by the Wars of the Roses allowed nobles to take advantage and promote their own position at the expense of others. This was because the 15th century CE witnessed the phenomenon of 'bastard feudalism' which involved the partial degradation of medieval feudalism. Rich landowners were able to possess private armies of retainers, accumulate wealth, and diminish the power of the Crown at a local level. Retainers, often sporting a badge to identify themselves as followers of a particular local lord, were subject to that lord's laws and were loyal to him rather than the king. The wealthiest barons thus became what some historians have called the 'over-mighty' because they were able to take over many of the functions of the royal government at a local level and have undue influence on the king at court. Some barons might even harbour ambitions of becoming king themselves, as was the case with Richard, Duke of York. Such a baron might, with a bit of royal blood through a distant relative, be able to command the loyalty of other barons who were keen to see a change of regime to gain more wealth and power for themselves, especially if they were out of favour with the incumbent monarch. The wars of the Roses perpetuated this power struggle by showing that a person not directly descended from the king could indeed take the throne, as was the case with Edward IV, Richard III, and Henry VII.

The Politics of Violence

The Wars of the Roses displayed an ever-increasing tendency to use violence to achieve political aims. The strategy of murdering a king and even their young heirs was begun by Henry Bolingbroke in 1399 CE when he became Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE). The first Lancaster king usurped the throne and murdered his predecessor Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE). It became feasible to convince people that the divine right of kings could be interpreted not only as any king should be descended from a king but also whoever had the competence to rule and the military power to keep it was similarly chosen by God to sit on the throne of England. In effect, the new policy was 'might is right' and eliminating one's rivals was an acceptable, even necessary manoeuvre. Once the line was crossed, there was no going back and executions, even of royal persons, became a standard feature during the next ruling dynasty, the Tudors.

Nobles & Battles

Tudor historians perhaps exaggerated the destruction and disruption caused by the Wars of the Roses in order to show that Henry Tudor and his successors were responsible for steadying the floundering ship of state but there were certainly dire consequences for some. It is true that the wars were largely fought between nobles and their private armies, and they were also intermittent with fewer than 24 months of actual fighting over the entire period. Nevertheless, the local populace was sometimes dragged into the conflict, especially if nobles formed militia from their estate workers.

Many battles were really little more than skirmishes with fewer than 100 casualties but there were some big field engagements, notably at the bloody Battle of Towton in March 1461 CE, the largest and longest battle in English history where around 28,000 men were killed (perhaps half of those involved). Even the number of casualties, though, is hard to determine in many battles as there were no official records made of these or of muster rolls or pay. There were also wider campaigns, such as in Northumberland and Wales in the 1460s CE, when the passage of troops no doubt affected local farmers and the economy as the soldiers pillaged with impunity. However, the wars did not involve any scorched earth tactics, no army stayed very long in one place, and many areas of the country were completely unaffected.

Over the four decades of the Wars of the Roses the nobility of England was severely reduced through deaths in battle, murder plots, and executions. Before the war started there were around 60 noble families, but by the end of it, this number had fallen to around 30. Besides the fact that many skirmishes involved exclusively nobles, another reason for the high death toll was that the traditional strategy of taking noble prisoners and then asking for a ransom for their release no longer functioned; nobody was willing to pay. In any case, the wars were of a dynastic nature and so the intention was not just to win the Crown but completely destroy the opposition in the process and prevent any future conflicts from arising. For this reason, there were no treaties or compromises during the wars, it was win all or lose all.

While ordinary troops were usually allowed to retreat back to their everyday lives, commanders and knights on the losing side were frequently executed, as witnessed by the number of tombs with armour-clad effigies that can be found in dark corners of many a country church across England. Consequently, over the four decades, the nobility lost one king on the battlefield and two by murder, eight dukes were killed, and a host of earls, barons, and viscounts lost their lives. One should not forget women, either. As husbands fell, so too did their wives' and daughters' chances of maintaining their previous life, property, marriage prospects or even freedom as many noble ladies were left impoverished or banished to convents. By the latter stages of the wars, then, many nobles saw the risks involved and became much more wary of involving themselves at all in the dynastic disputes.

The Resurgence of the Crown

At the end of the wars, Henry VII benefitted from this situation of a much-reduced nobility because the Crown became richer via confiscated lands or those acquired from deceased families. The king notably acquired the estates of the Yorkist families of Warwick, Clarence, and Gloucester. In addition, Henry ensured that only the Crown had any authority to maintain armies, he limited the number of retainers a nobleman could employ, and he personally ensured noble families did not form powerful alliances through marriages. At the same time, the Crown was enriched by charging loyalty fees and fines for those nobles deemed as suspect in their political leanings.

The power of the nobility had increased prior to and during the Wars of the Roses, but by the end, the advantage had very much swung back into the monarch's favour. Henry would further benefit from the stability of his kingdom and the resulting resurgence in trade with mainland Europe. Finally, it is perhaps important to note that despite the changes in who held which title and which estates, the general ownership of wealth did not change in the 15th century CE. Yes, there was an undignified shuffling of seats amongst the elite but still, the king, nobility and clergy together - only 3% of the total population - continued to own 95% of the country's wealth.

The Creation of the Tudors

Henry VII, a descendant of the Lancastrian John of Gaunt, a son of Edward III, reunited the two rival houses by marrying Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV in 1486 CE, thus creating the new house of Tudor. There was even a new symbol for this new dynasty: the Tudor Rose which combined the roses of the Lancasters and Yorks. Henry still had a few conspiracists to deal with, notably facing a Yorkist revival centred around the pretender Lambert Simnel, but this was quashed at the Battle of Stoke Field in June 1487 CE. This was the last act of the Wars of the Roses, even if there were some more minor revivals on the part of the Yorkists over the next half-century. Henry had managed to unite his kingdom. The mark of his success is that Henry's son Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) became king without any wrangling and that the Tudors went on to provide the next three monarchs after him in a period of English history seen as its Golden Age. The Tudor Dynasty would rule England uninterrupted until 1603 CE and see such important events as the Church of England's split from Rome in the 1530s CE and the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588 CE.

Cultural Legacy

The Wars of the Roses might not have seemed anything like a coherent series of conflicts to the people who lived through them but they have certainly caught the imagination of later writers and historians as a fascinating if brutal period of English history. Indeed, the very name for the conflict was first coined by a novelist, Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832 CE), after the later badges of the two main families involved (neither of which were actually the favoured liveries at the time). This romantic but simplistic label masks the fact that the division was more complex than merely two families as each one garnered allies amongst England's other noble families and some were even liable to switch allegiances over the course of the conflict. So complex is the whole affair and so disjointed are the major episodes, that historians continue to debate its precise origins, start, finish, and even very existence as a recognisable and coherent set of historical events.

One of the writers who showed the most interest in the period of the Wars of the Roses, and certainly the most influential on the popular imagination, was William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE). Focussing his plays on the kings of the period, episodes from the Wars of the Roses appear in such works as Henry VI (parts 1-3) and Richard III, providing some of the playwright's most memorable characters and oft-quoted lines. Even today the Wars of the Roses and the idea of two families ruthlessly competing for power continue to inspire writers, perhaps most notably George R. R. Martin whose novels have in turn inspired the television series Game of Thrones.