The Battle of the Eurymedon (c. 466 BCE, also given as the Battle of the Eurymedon River) was a military engagement between the Greeks of the Delian League and the forces of the Achaemenid Empire toward the end of the reign of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE). The battle took place at the mouth of the Eurymedon River in Asia Minor (modern-day Koprucay River in Antalya Province, Turkey) and was both a naval and land engagement. The Greek forces were led by Cimon of Athens (l. c. 510 - c. 450 BCE) to a complete victory over the Persians.

The second Persian invasion of Greece had been repelled in 479 BCE and, in the aftermath, the Ionian Greek city-states of Asia Minor had asserted their autonomy, resisting Persian rule. Cimon sailed to the region to encourage further resistance, and the Persians responded by gathering a fleet, which would work in concert with their land forces to defeat Cimon and subdue these cities which could then be used to launch a third invasion of Greece.

Cimon's victory at the Eurymedon ended any hope of such an action and demoralized the Persian monarch and military. Xerxes I's son and successor, Artaxerxes I (r. 465-424 BCE) would resort to less obvious methods of striking at the Greek city-states, notably by fueling the tensions between Athens and Sparta which would lead to the Peloponnesian Wars (460-446 and 431-404 BCE) and, eventually, Athens' defeat by the Spartans.

Date & Sources

Although the battle is frequently given as c. 466 BCE, it is also dated to 469 BCE or 468 BCE. Scholars are divided on when exactly it happened because the history of this entire period, known as the Pentecontaetia (“period of the fifty years”) is poorly attested in the primary sources. The Pentecontaetia is often incorrectly understood as “fifty years of peace” when it was not. Many battles were fought between the Greek city-states during this time even though it was, overall, a period of growth and development – especially for Athens and Sparta.

The period is better understood as the time between the defeat of the second Persian invasion of Greece in 479 BCE and the outbreak of the Second Peloponnesian War in 431 BCE. The historians of the time, such as Thucydides, often do not provide careful chronology or developmental details in their narratives, seeming to assume an audience would already have this information.

The primary sources for the battle are Thucydides (l. c. 460 - c. 400 BCE), Diodorus Siculus (l. c. 90 - c. 30 BCE), and Plutarch (l. c. 45 - c. 125 CE), with Thucydides and Plutarch considered the most reliable (Thucydides because he was writing close to the event and Plutarch because of the sources available to him). Even so, as noted, neither were careful with the chronology of the period and so any of the above dates for the battle could be correct. The date of c. 466 BCE, however, seems to make the most sense in light of other events – whose dates are known – which fit with this chronology.

Background

The Achaemenid Persian Empire was founded by Cyrus II (the Great, r. c. 550-530 BCE) c. 550 BCE and by the time of the king Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) controlled territories from the border with India to the east across to Asia Minor in the west, up through Mesopotamia, and down through Egypt. A number of Greek city-states had been founded along the coast of Asia Minor prior to Cyrus II's conquest and were now under Persian control.

In 499 BCE, these city-states rebelled against Persian rule and were supported by Athens and Eretria. The revolt took five years to put down and, afterwards, Darius I began preparations to punish Athens and Eretria for their interference and also expand his empire by taking Greece. He launched his invasion in 490 BCE and sacked Eretria but was defeated at the Battle of Marathon that same year by the Athenians and withdrew. His son, Xerxes I, then launched the second invasion to avenge his father's defeat in 480 BCE and punish Athens but was also defeated. Xerxes I did manage to burn Athens but did not defeat the Athenians nor subjugate them as both he and his father had hoped to do.

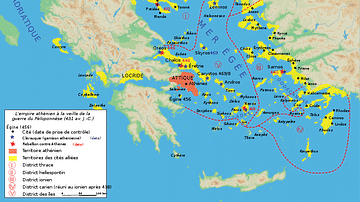

In response to Persian aggression, the Athenians formed the Delian League in 478 BCE. This was an alliance of Greek city-states who banded together to help liberate Greeks from Persian rule and defend against any future invasions. The league took its name from the island of Delos – considered a sacred space not aligned with any of the members – where the league's treasury was kept and all agreed to be led by Athens, the city-state considered most effective in repelling the two invasions of the Persian Wars.

Athens had created the largest navy in Greece and, under the direction of the statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE), had rebuilt the city, including the acropolis with its Parthenon. Athens clearly thought of itself as the leader of the Greeks whose city should embody its high status through grand building projects as well as new walls to surround it. These activities were not appreciated by the Spartans, who were already tired of Athenian arrogance, and the greater Athens grew, so did the tensions between the two city-states.

With their powerful navy, Athens and the Delian League were able to easily eliminate piracy from the surrounding area and also provide aid and support to the Greek cities along the coast of Asia Minor. The league's ships also regularly transported troops to various Persian-held territories to liberate them while, at the same time, filling their treasury with the riches either taken from these places or given as gifts. These actions primarily benefited Athens which further alarmed Sparta. Although the league was primarily overseen by Pericles, the operations were carried out by the general Cimon.

Persian Response

Prior to their defeat in 480 BCE, the Persians would have mounted some kind of military response to the Delian League's activities, but Xerxes I had been completely demoralized by the event. Historians have often noted that, to the Greeks, the victories at Marathon, Salamis, and Platea were epic in their importance while, to the Persians, they were seen as minor setbacks in reaching an ultimately achievable goal. While there may be some truth to this overall, it certainly does not apply to Xerxes I whose character, and reign, disintegrated after his defeat. He spent more time in his harem at Persepolis than attending to matters of state and otherwise was only interested in completing his building projects. Whatever Athens was doing, it seemed, could not possibly matter to Xerxes I but, if he heard of its resurgence – as he probably did – it most likely added to his depression.

He roused himself when Cimon began operations directly targeting the city-states of Asia Minor. Cimon took 200 ships across the sea and landed at Caria sometime in 467-466 BCE from whence he sought to aid those cities which had declared their autonomy and joined the Delian League and force others, still loyal to Persia, to rebel and free themselves. A number of these city-states had no desire to leave the Persian Empire, however, recognizing they enjoyed a level of civil rights, prosperity, and security that no Greek mainland city-state could offer.

Xerxes I, alerted to Cimon's action, finally returned to himself and ordered preparations for a large force to deal with the Greek aggression. He placed the general Ariomandes in charge of the overall operation with Pherendates in charge of the land troops and Xerxes I's son Tithraustes in charge of the fleet of over 200 vessels. This army gathered near the Eurymedon with the plan for the land forces to march up the coast, subduing rebel states, supported by the fleet which would neutralize Cimon. Once the city-states were firmly under Persian control again, and Cimon defeated, Asia Minor would have served well in launching a third invasion of Greece.

The Battle

The Persian forces had gathered and were waiting for 80 ships from the Phoenicians to join them when Cimon received word of their location. He instantly broke off his engagements to meet them. The Persian fleet, not wanting to begin battle before the Phoenician ships arrived, moved into the mouth of the Eurymedon River thinking Cimon would not follow them.

Cimon, however, moved to attack and Ariomandes, understanding his ships would do better with more room to maneuver, came back out from the river to give battle in open water. He meanwhile ordered his land troops away from the shore to protect the camp and supplies. Cimon attacked and broke the Persian line. Ariomandes ordered a retreat back into the river where he grounded the ships on the bank and the crews joined with the land forces in forming a defensive position.

The Greek fleet followed, and Cimon ordered his ships to also be grounded, disembarking his crews. He then sent his heavily armored hoplites to break the Persian lines. The Persians held at first but then broke and Cimon sent in his reserves, which scattered the Persian forces. The Greeks pursued them inland where they captured their camp with all their supplies, and the Persian commanders were left with no choice but surrender.

This is the version of the battle given by Thucydides and Plutarch. Diodorus Siculus gives a different account with more colorful detail:

And when Cimon learned that the Persian fleet was lying off Cyprus, sailing against the barbarians he engaged them in battle, pitting two hundred and fifty ships against three hundred and forty. A sharp struggle took place and both fleets fought brilliantly, but in the end the Athenians were victorious, having destroyed many of the enemy ships and captured more than one hundred together with their crews. The rest of the ships escaped to Cyprus, where their crews left them and took to the land, and the ships, being bare of defenders, fell into the hands of the enemy.

Thereupon Cimon, not satisfied with a victory of such magnitude, set sail at once with his entire fleet against the Persian land army, which was then encamped on the bank of the Eurymedon River. And wishing to overcome the barbarians by a stratagem, he manned the captured Persian ships with his own best men, giving them tiaras for their heads and clothing them in the Persian fashion generally.

The barbarians, so soon as the fleet approached them, were deceived by the Persian ships and garb and supposed the triremes to be their own. Consequently, they received the Athenians as if they were friends. And Cimon, night having fallen, disembarked his soldiers, and being received by the Persians as a friend, he fell upon their encampment. A great tumult arose among the Persians, and the soldiers of Cimon cut down all who came in their way, and seizing in his tent Pheredates, one of the two generals of the barbarians and a nephew of the king, they slew him; and as for the rest of the Persians, some they cut down and others they wounded, and all of them, because of the unexpectedness of the attack, they forced to take flight.

In a word, such consternation as well as bewilderment prevailed among the Persians that most of them did not even know who it was that was attacking them. For they had no idea that the Greeks had come against them in force, being persuaded that they had no land army at all; and they assumed that it was the Pisidians, who dwelt in neighboring territory and were hostile to them, who had come to attack them.

Consequently, thinking that the attack of the enemy was coming from the mainland, they fled to their ships in the belief they were in friendly hands. And since it was a dark night without a moon, their bewilderment was increased all the more and not a man was able to discern the true state of affairs. Consequently, after a great slaughter had occurred on account of the disorder among the barbarians, Cimon, who had previously given orders to the soldiers to come running to the torch which would be raised, had the signal raised beside the ships, being anxious lest, if the soldiers should scatter and turn to plundering, some miscarriage of his plans might occur.

And when the soldiers had all been gathered at the torch and had stopped plundering, for the time being they set up a trophy and then sailed back to Cyprus, having won two glorious victories, the one on land and the other on the sea; for not to this day has history recorded the occurrence of so unusual and so important actions on the same day by a host that fought both afloat and on land. (XI.60.6-7, 61.1-7)

Diodorus cites no source for this account of the battle, and it appears nowhere else except in later works citing his own. The tone and details of Diodorus' version have been noted as typical of cultural and nationalistic myths and so his account is usually disregarded. Since historians recognize the poor attestation of this period, however, it is possible that Diodorus was working from a source unavailable to the others and his account may actually have some elements of truth to it.

Conclusion

All three narratives make clear that the battle was a complete victory for Cimon; the Persian forces were unable to regroup or counterattack at any time afterwards. What, exactly, did happen after the battle is unclear. Cimon had won a stunning victory but there is no record of him pressing his advantage nor any regarding what happened to the defeated Persian army.

Athens was engaged in the First Peloponnesian War with Corinth at the time so it is understandable the Athenians would not want to divide their forces or spend any more time than necessary in Asia Minor, but they had already done so with Cimon's initial expedition and would do so again 460-454 BCE in lending military support to an Egyptian revolt against Persian rule.

Perhaps the simplest reason for Cimon not pursuing his advantage is that he had no need to. He had come to Asia Minor to help the Ionian Greeks and was now free to liberate whatever cities he wanted to up the coast of Asia Minor from Caria onwards without having to worry about any Persian opposition. Scholar A. T. Olmstead sums up the result of the Persian defeat:

Eurymedon was decisive…Europe had been lost to the [Persian] empire; and now large numbers of the Asiatic Greeks, together with many Carians and Lycians, were enrolled in the rapidly expanding Delian League. (268)

There would be no third invasion of Greece and Xerxes I was assassinated the following year; not, as legend claims, for anything having to do with Eurymedon but by his court officer and bodyguard Artabanus who wanted to establish his own dynasty. Artabanus was quickly executed by Artaxerxes I who, having learned that Persian warfare with the Greeks did not end well, opted for a different course of action.

He wooed the Spartans and Athenians with vast sums of gold, promising help to Athens while secretly funding a Spartan military build-up. Tensions between the two city-states erupted in the First Peloponnesian War (460-446 BCE), which was fought primarily between Athens and Corinth (an ally of Sparta) to a draw. In the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE)), however, Athens and Sparta confronted each other directly, with Sparta aided and funded by the Persians. When the war was over, Athens was in ruins, and even though he did not live to see it, Artaxerxes I had finally accomplished what neither his father nor his grandfather had been able to.