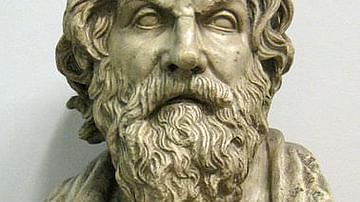

Xenophon's Defense of Socrates (c. 371 BCE) is a passage from the Memorabilia of Xenophon (l. 430 to c. 354 BCE) in which he addresses the teachings and actions of Socrates of Athens and denounces the charges against him as unjust and unfounded. It is one of three extant works on Socrates' trial written by those who knew him.

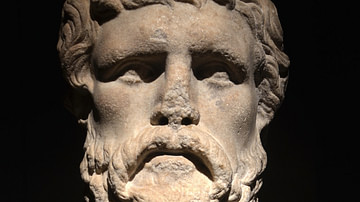

The other two works are Xenophon's Apology and the Apology of Plato (l. 424/423-348/347 BCE). Xenophon and Plato were both young Athenian followers of Socrates of Athens (l. 470/469-399 BCE), and although other students such as Antisthenes of Athens (l. c. 445-365 BCE) and Aristippus of Cyrene (l. c. 435-356 BCE) founded Socratic schools (as did Plato through his famous Academy), only Plato and Xenophon are known to have written contemporary or near-contemporary accounts of Socrates' 399 BCE trial and execution.

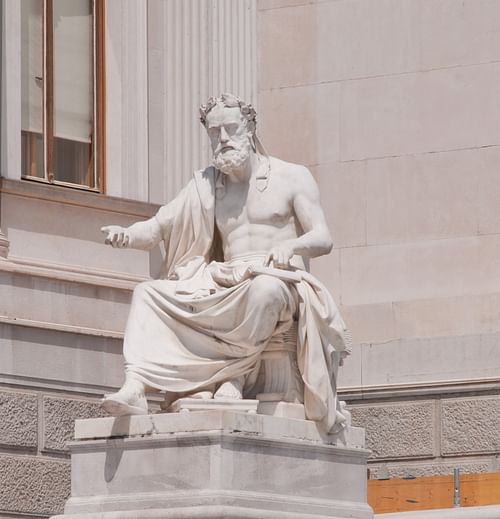

Xenophon's Defense of Socrates should not be confused with Xenophon's Apology. The Defense is part of the longer work Memorabilia, a collection of remembrances of Xenophon's time with Socrates, while his Apology is a recreation of the trial with personal commentary on the event. Xenophon is best known as the mercenary general who wrote the Anabasis, relating his leadership of the Ten Thousand Greek mercenaries and their retreat back to Greece after the disastrous campaign of Cyrus the Younger (d. 401 BCE) against his brother Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358 BCE) for control of the Persian Achaemenid Empire.

The Anabasis has long been considered a classic and was used by Alexander the Great as a field guide for his own successful campaigns in Persia beginning in 334 BCE. Xenophon's Memorabilia is also highly regarded, however, for its depiction of Socrates as a friend and neighbor rather than, as in Plato's works, as the idealistic philosopher and seeker of truth. The Defense of Socrates maintains the same depiction as the rest of Memorabilia in presenting Socrates as an honest man and loyal friend unjustly accused and condemned, even though the evidence of his daily life should have been proof enough of his innocence.

Background to the Work

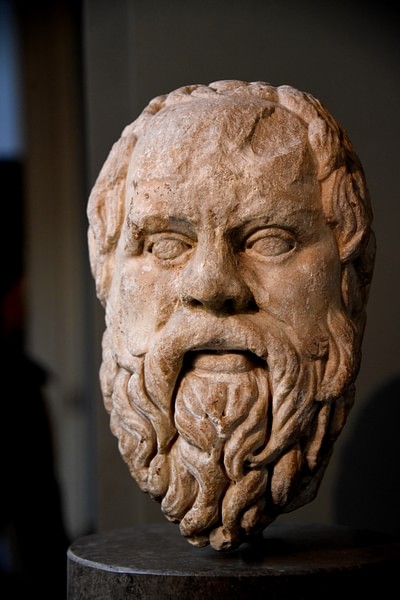

Socrates was initially a sculptor, served in the Athenian army, married, and had three sons. There was nothing exceptional about his life until, according to Plato and Xenophon, his friend Chaerephon asked the Oracle at Delphi if there lived anyone wiser than Socrates. The oracle replied, "None," and Socrates, unwilling to accept this, began questioning those who were thought wise by their fellow citizens. According to Plato, Socrates found that "the men whose reputation for wisdom stood highest were nearly the most lacking in it, while others who were looked down on as common people were much more intelligent" (Apology, 22). He concluded, finally, that he was indeed the wisest man living only because he did not claim to know anything at all.

His quest, however, attracted a number of young Athenians who enjoyed watching him ask their elders questions they were not able to answer. Initially a source of entertainment, Socrates' conversations with his fellow Athenians and various travelers eventually inspired a number of youths to abandon whatever they had been pursuing as a career and devote themselves to the study of philosophy.

At this same time, the elders of Athens, tired of being made fools of, accused Socrates of impiety, a capital crime. His three accusers, Meletus the poet, Anytus the tanner, and Lycon the orator, all claimed he denied the gods of the state, introduced new divinities, and corrupted the youth of Athens. Socrates was found guilty of these charges and sentenced to death in 399 BCE. Plato's dialogue of the Phaedo relates his last day and execution by drinking hemlock.

The Text

Plato's Apology is usually dated to between 399-387 BCE and Xenophon's to c. 385 BCE, while the Defense, as part of Memorabilia, is dated to c. 371 BCE. Unlike his earlier Apology, the Defense is a reflection upon the trial and Socrates' life overall. Xenophon makes a point of showing how deeply Socrates cared for his fellow citizens and how piously he observed religious rituals in highlighting the injustice of the accusations against him and his condemnation.

Passage 6 below seems to reference a famous story concerning the young Xenophon and Socrates (as given by Xenophon in Anabasis 3.1.5-7). Xenophon asked Socrates whether he should join the expedition of Cyrus the Younger and Socrates sent him to ask the question of the god of the Oracle at Delphi. Xenophon apparently went to Delphi and instead asked the Oracle which of the gods would be most profitable to pray to for a successful expedition and safe return home and the god answered him. When he returned to Athens from the trip to Delphi and told Socrates what he had done, his teacher scolded him for asking the wrong question but, as the god had seemed to answer him, advised him to listen and go to war.

The following passage is from the 1883 translation of Memorabilia by J. S. Watson:

1. I have often wondered by what arguments the accusers of Socrates persuaded the Athenians that he deserved death from the state; for the indictment against him was to this effect: Socrates offends against the laws in not paying respect to those gods whom the city respects, and introducing other new deities; he also offends against the laws in corrupting the youth.

2. In the first place, that he did not respect the gods whom the city respects, what proof did they bring? For he was seen frequently sacrificing at home, and frequently on the public altars of the city; nor was it unknown that he used divination; as it was a common subject of talk that "Socrates used to say that the divinity instructed him;" and it was from this circumstance, indeed, that they seem chiefly to have derived the charge of introducing new deities.

3. He however introduced nothing newer than those who, practicing divination, consult auguries, voices, omens, and sacrifices; for they do not imagine that birds, or people who meet them, know what is advantageous for those seeking presages, but that the gods, by their means, signify what will be so; and such was the opinion that Socrates entertained.

4. Most people say that they are diverted from an object, or prompted to it, by birds, or by the people who meet them; but Socrates spoke as he thought, for he said it was the divinity that was his monitor. He also told many of his friends to do certain things, and not to do others, intimating that the divinity had forewarned him; and advantage attended those who obeyed his suggestions, but repentance those who disregarded them.

5. Yet who would not acknowledge that Socrates wished to appear to his friends neither a fool nor a boaster? But he would have seemed to be both, if, after saying that intimations were given him by a god, he had then been proved guilty of falsehood. It is manifest, therefore, that he would have uttered no predictions, if he had not trusted that they would prove true. But who, in such matters, would trust to anyone but a god? And how could he, who trusted the gods, think that there were no gods?

6. He also acted toward his friends according to his convictions, for he recommended them to perform affairs of necessary consequence in such a manner as he thought that they would be best managed; but concerning those of which it was doubtful how they would terminate, he sent them to take auguries whether they should be done or not.

7. Those who would govern families or cities well, as he said, had need of divination; for to become skillful in architecture, or working in brass, or agriculture, or in commanding men, or to become a critic in any such arts, or a good reasoner, or a skillful regulator of a household, or a well-qualified general, he considered as wholly matters of learning, and left to the choice of the human understanding.

8. But he said that the gods reserved to themselves the most important particulars attending such matters, of which nothing was apparent to men; for neither was it certain to him who had sown his field well, who should reap the fruit of it; nor certain to him who had built a house well, who should inhabit it; nor certain to him who was skilled in generalship, whether it would be for his advantage to act as a general; nor certain to him who was versed in political affairs, whether it would be for his profit to be at the head of the state; nor certain to him who had married a beautiful wife in hopes of happiness, whether he should not incur misery by her means; nor certain to him who had acquired powerful connections in the state, whether he might not be banished by them.

9. And those who thought that none of these things depended on the gods, but that all were dependent on the human understanding, he pronounced to be insane; as he also pronounced those to be insane who had recourse to omens respecting matters which the gods had granted to men to discover by the exercise of their faculties; as if, for instance, a man should inquire whether it would be better to take for the driver of his chariot one who knows how to drive, or one who does not know; or whether it would be better to place over his ship one who knows how to steer it, or one who does not know; or if men should ask respecting matters which they may learn by counting, or measuring, or weighing; for those who inquired of the gods concerning such matters he thought guilty of impiety, and said that it was the duty of men to learn whatever the gods had enabled them to do by learning, and to try to ascertain from the gods by augury whatever was obscure to men; as the gods always afford information to those to whom they are rendered propitious.

10. He was constantly in public, for he went in the morning to the places for walking and the gymnasia; at the time when the market was full, he was to be seen there; and the rest of the day he was where he was likely to meet the greatest number of people; he was generally engaged in discourse, and all who pleased were at liberty to hear him.

11. Yet no one ever either saw Socrates doing, or heard him saying, anything impious or profane; for he did not dispute about the nature of things as most other philosophers disputed, speculating how that which is called by sophists the world was produced, and by what necessary laws everything in the heavens is effected, but endeavored to show that those who chose such subjects of contemplation were foolish.

12. And used in the first place to inquire of them whether they thought that they already knew sufficient of human affairs, and therefore proceeded to such subjects of meditation, or whether, when they neglected human affairs entirely, and speculated on celestial matters, they thought that they were doing what became them.

13. He wondered, too, that it was not apparent to them that it is impossible for man to satisfy himself on such points, since even those who pride themselves most on discussing them, do not hold the same opinions one with another, but are compared with each other, like madmen.

14. For of madmen some have no fear of what is to be feared, and others fear what is not to be feared; some think it no shame to say or do anything whatever before men, and others think that they ought not to go among men at all; some pay no respect to temple, or altar, or anything dedicated to the gods, and others worship stones, and common stocks, and beasts: so of those who speculate on the nature of the universe, some imagine that all that exists is one, others that there are worlds infinite in number; some that all things are in perpetual motion, others that nothing is ever moved; some that all things are generated and decay, and others that nothing is either generated or decays.

15. He would ask, also, concerning such philosophers, whether, as those who have learned arts practiced by men, expect that they will be able to carry into effect what they have learned, either for themselves, or for anyone else whom they may wish, so those who inquire into celestial things, imagine that, when they have discovered by what laws everything is effected, they will be able to produce, whenever they please, wind, rain, changes of the seasons, and whatever else of that sort they may desire, or whether they have no such expectation, but are content merely to know how everything of that nature is generated.

16. Such were the observations which he made about those who busied themselves in such speculations; but for himself, he would hold discourse, from time to time, on what concerned mankind, considering what was pious, what impious; what was becoming, what unbecoming; what was just, what unjust; what was sanity, what insanity; what was fortitude, what cowardice; what a state was, and what the character of a statesman; what was the nature of government over men, and the qualities of one skilled in governing them; and touching on other subjects, with which he thought that those who were acquainted were men of worth and estimation, but that those who were ignorant of them might justly be deemed no better than slaves.

17. As to those matters, then, on which Socrates gave no intimation what his sentiments were, it is not at all wonderful that his judges should have decided erroneously concerning him; but is it not wonderful that they should have taken no account of such things as all men knew?

18. For when he was a member of the senate, and had taken the senator's oath, in which it was expressed that he would vote in accordance with the laws, he, being president in the assembly of the people when they were eager to put to death Thrasyllus, Erasinides, and all the nine generals, by a single vote contrary to the law, refused, though the multitude were enraged at him, and many of those in power uttered threats against him, to put the question to the vote, but considered it of more importance to observe his oath than to gratify the people contrary to what was right, or to seek safety against those who menaced him.

19. For he thought that the gods paid regard to men, not in the way in which some people suppose, who imagine that the gods know some things and do not know others, but he considered that the gods know all things, both what is said, what is done, and what is meditated in silence, and are present everywhere, and give admonitions to men concerning everything human.

20. I wonder, therefore, how the Athenians were ever persuaded that Socrates had not right sentiments concerning the gods; a man who never said or did anything impious toward the gods but spoke and acted in such a manner with respect to them, that any other who had spoken and acted in the same manner, would have been, and have been considered, eminently pious.

Conclusion

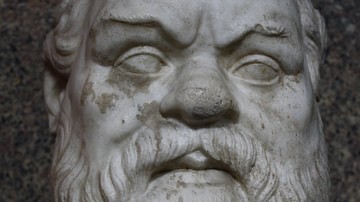

Xenophon's depiction of Socrates provides an interesting counterpoint to Plato's more idealized vision of the philosopher as, in the Defense, as throughout Memorabilia, he highlights Socrates' practical advice and how he felt human relationships and one's individual responsibilities were more important than idle speculation on gods or truth (as in point 12 above). Xenophon seems to have taken his teacher's values to heart concerning personal responsibility, self-control, and perseverance, as he displays all these in the course of the march back to Greece described in the Anabasis.

Xenophon also seems to have emulated his old master later in life when he lived in Scillus (in Elis) near Olympia after he was exiled from Athens for fighting against his home city-state with the Spartans at the Battle of Coronea in 394 BCE. Xenophon purchased land and built a temple in honor of the goddess Artemis and funded her annual festival, providing for his fellow citizens just as Socrates would have suggested one should. Like his teacher, his efforts went finally unappreciated, and when the Spartans, who had granted him his estate in Elis, lost the Battle of Leuctra in 371 BCE, the Elians confiscated his lands, and he was forced to leave for Corinth, where he is said to have died.