The Hundred Years' War was fought intermittently between England and France from 1337 to 1453 CE and the conflict had many consequences, both immediate and long-lasting. Besides the obvious death and destruction that many of the battles visited upon soldiers and civilians alike, the war made England virtually bankrupt and left the victorious French Crown in total control of all of France except Calais. Kings would come and go but for many of them, one significant measure of the success of their reign was their performance in the Hundred Years' War. Divisions were created within the nobilities of both countries which had repercussions for who became the next ruling monarch. Trade was badly affected and peasants were incessantly taxed, which caused several major rebellions, but there were more positive developments such as the creation of more competent and regularised tax offices and the trend towards more professional diplomacy in international relations. The war also produced enduring and iconic national heroes, notably Henry V of England (r. 1413-1422 CE) and Joan of Arc (1412-1431 CE) in France. Finally, such a long conflict against a clearly identifiable enemy resulted in both participants forging a much greater sense of nationhood. Even today, a rivalry still continues between these two neighbouring countries, now, fortunately, largely expressed within the confines of international sporting events.

The consequences and effects of the Hundred Years' War may be summarised as:

- The loss of all English-held territory in France except Calais.

- A high number of casualties amongst the nobility, particularly in France.

- A decline in trade, especially English wool and Gascon wine.

- A great wave of taxes to pay for the war which contributed to social unrest in both countries.

- Innovations in forms of tax collection.

- The development of a stronger Parliament in England.

- The almost total bankruptcy of the English treasury at the war's end.

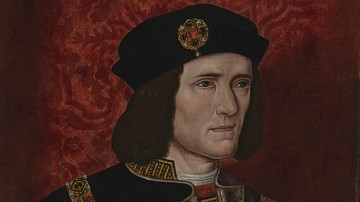

- The disagreement over the conduct of the war and its failure fuelled the dynastic conflict in England known as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE).

- The devastation of French towns and villages by mercenary soldiers between battles.

- Developments in weapons technology such as cannons.

- The consolidation of the French monarch's control over all of France.

- A greater use of international diplomacy and specialised diplomats.

- A greater feeling of nationalism amongst the populations of both countries.

- The creation of national heroes, notably Henry V in England and Joan of Arc in France.

- A tangible rivalry between the two nations which still continues today, seen particularly in sports such as football and rugby.

Death & Taxes: The Economics of Failure

Beyond the immediate consequences of England's failures in the war such as the loss of all territory except Calais and France's defeats in the large-scale battles which saw a huge number of nobles killed, there were many more, deeper and subtler effects of this 116-year conflict. There were also consequences which occurred long before the war had even ended as successive monarchs on either side struggled with the problems created by their predecessors. Finally, the conflict had an impact which lasted for decades and centuries after it had long finished.

In England, many barons had become extremely rich as their power increased at local level and the king became correspondingly weaker and poorer as the barons kept local revenues to themselves. The king could not tax his people without the permission of Parliament and so this body had to be called each time a monarch required more cash for his campaigns in France or elsewhere. As a result of Parliament frequently meeting, it did not necessarily gain any new powers but it did create for itself an identity and, by being involved in diplomatic policy discussions and the ratification of peace treaties, the institution was starting to become a part of English political life. The 'Long Parliament' of 1406 CE, for example, sat an unusually long time from March until December as it deliberated over the ever-prickly issue of state finances, and there was very much a feeling that the king, although still an absolute monarch, was perhaps just a little less absolute than before the war.

In France, the opposite was true as the monarchy's position was strengthened because of the success of the war while that of the nobility and the Estates General (the legislative assembly) weakened. This was because the king did not need to consult anyone else regarding taxation policies which could be levied at will to pay for the war. The conflict also saw the introduction of long-lasting indirect taxes such as the salt tax (gabelle) that was not abolished until the French Revolution of the late 18th century CE. The French monarch was thus able to triple his income through taxes from the start to the end of the war. Further, such taxes required a whole new state apparatus of tax collectors, keepers of public records, and assessors for payment disputes, ensuring the sustained enrichment of the Crown.

In England, there was often disagreement amongst the nobles of England as to how to best conduct the war against France, indeed even whether to conduct it at all. This became more serious in times of failure but the final loss in 1453 CE was one of the reasons Henry VI of England (r. 1422-61 & 1470-71 CE) became so unpopular and it was probably a contributory factor to the king's episodes of madness. This dissatisfaction with the monarch, his obvious aversion to warfare and the inevitable search for scapegoats for the loss of the war ultimately led to the dynastic conflict known to history as the Wars of the Roses (1455-1487 CE). In addition, now that the war with France was over, English nobles dissatisfied with the current regime could better use their own private armies as a tool to increase their own wealth and influence. Another consequence was the sheer number of nobles as monarchs often created more aristocrats - two new ranks in England were (e)squire and gentlemen - as they sought to increase their tax base. Indeed, during the war, the nobility of England tripled in size as new members qualified via property ownership rather than just hereditary titles (although it was still under 2% of the total population in the mid-15th century CE).

At a lower level in society, the slump in trade caused by the war brought economic hardship for many. English wool was a major export to the clothmakers in the Low Countries, and this trade was disrupted. In the other direction, the quantity of wine imported from Gascony crashed (from 74,000 tuns/barrels in 1336 CE to 6,000 tuns in 1349 CE), a trade which never really recovered. Sailing vessels were frequently commandeered by the state to ferry armies across to France; herring fishermen were particularly susceptible to this state interference in their livelihoods. Piracy was another blow to merchants, as were such direct raids as the French attack on Southampton in 1338 CE, not to mention the random pillaging of armies throughout the war, both in France where the battles were fought but also in southeast England where armies were stationed prior to embarkation to the Continent.

The poor economic situation of many communities was only worsened by taxes - Edward III of England (r. 1327-1377 CE), for example, had called for taxes 27 times during his reign. The Peasants' Revolt of June 1381 CE was the most infamous popular uprising of the Middle Ages as ordinary folk protested at the huge problems caused by the Black Death plague and, above all, the never-ending taxes which, since 1377 CE, included indiscriminate poll taxes. The rebellion of 1450 CE led by Jack Cade again saw commoners protest at high taxes, perceived corruption at court, and an absence of justice at local level. The commoners might not have had any direct influence on government but the discord did perhaps give those nobles keen to overthrow the regime another excuse to do so beyond merely extending their own interests.

In France, too, the general population was, as we have seen, subject to taxes to pay for the war but they had to endure the additional problem of marauding armies. Although, highly localised to battle areas and main roads, some towns and villages were ravaged by bands of mercenary soldiers (routiers) before and after battles. Soldiers brought diseases, took away grain, cattle and produce, and left behind only despair. The problem was particularly prevalent in Brittany, Périgord, and Poitou. In addition, Edward III had deliberately employed the strategy of chevauchées - striking terror into local populations by burning crops, raiding stocks and permitting general looting prior to his battles in the hope of drawing the French king into open battle. Finally, the civil war between the French nobility which involved the two rival groups of Burgundians and Armagnacs fighting for who should control and then succeed the mad Charles VI of France (r. 1380-1422 CE) brought further distress to local populations. Even those who avoided a direct loss of property often suffered from a crash in rent values, down by up to 40% in places like Anjou, or a hike in food prices, which went up by 50% during the siege of Reims, for example, in 1359 CE.

The Church

The medieval Church as an institution on either side tended to support the war, giving patriotic services, saying prayers, and ringing out bells whenever there was a victory. The Christian faith, though, did receive some challenges on a pan-European scale. The Great Schism of 1378 CE (aka Western Schism) in the Catholic Church ultimately saw three popes all in office at the same time. The situation was not resolved until 1417 CE as the rival camps jockeyed for the support of French and English kings. Further, the Church in Rome was weakened as the kings of England and France sought to limit taxes going to anywhere else except their own military campaigns. A consequence of this policy was the creation of 'national churches' in each country. Local churches also became the hubs of community news with news of the wars' events being posted on their noticeboards and official communications being read out in the preacher's pulpit.

New Weapons

As each side strived to better the other, weapons, armour, fortifications, and strategies of warfare developed during the war, and armies became more and more professional. By the wars' end, Charles VII created France's first permanent royal army. Notably, the use of archers armed with powerful longbows by English armies brought great success as the importance of heavy cavalry diminished and there was a tendency for medieval knights on both sides to fight on foot. Gunpowder weapons were first used at the Battle of Crécy in 1346 CE but, still crude in design, they had no great influence on the English victory. The French did use small handheld cannons to great effect at the battles of Formigny (1450 CE) and Castillon (1453 CE). From around 1380 CE, there were also giant cannons known as 'bombards' which could fire massive stone balls weighing up to 100 kilos (220 lbs). Such guns were too heavy and cumbersome to use in field engagements but they were especially useful in siege warfare such as at Harfleur in September 1415 CE.

Finally, an oft-neglected weapon developed over the period of the war was diplomacy. On both sides, but first to a higher degree in England, monarchs relied on a team of specialised diplomats and archive-keepers who could use their skills in language, law, and cultural awareness to forge useful alliances, persuade defections from the enemy, arrange the payment of ransoms, and negotiate the best terms for treaties. The international politics of the Hundred Years War, which involved several states (France, England, Spain, the Low Countries, Scotland and others), consequently saw the regular participation of experienced diplomats, forming what would soon become a formal body of ambassadors and embassies which we recognise today as an essential part of international relations.

The Birth of Nations & National Heroes

The war, boosted by stirring medieval literature, poems and popular songs, fostered a greater feeling of nationalism on both sides. Kings appealed to their armies prior to battles to fight for their king and country. The French monarchy was ultimately seen as the saviour of the country which went on to absorb such regions as Brittany, Provence, Burgundy, Artois, and Roussillon, thus the state largely took the form we know today. On the other side of the Channel, England's great battlefield victories were celebrated with popular processions welcoming back heroic kings such as Edward III and Henry V and those monarchs who failed on the battlefield suffered seriously in the popularity stakes back home. The same was true in France, as the historian G. Holmes puts it: "The war with England was to some extent the anvil upon which the identity of early modern France was forged" (301).

Another consequence of the military successes was the revival of medieval chivalry, especially by Edward III who, along with his son Edward the Black Prince (1330-1376 CE), founded the exclusive chivalric Order of the Garter c. 1348 CE which still survives today. Saint George, the patron of the order, was now firmly established as a national saint of a confident country finally on equal military terms with the French. By the end of the war, England became wholly separated from the affairs of the Continent and was already moving towards a more 'English' cultural identity where the English language was spoken at court and used in official documents, and where customs and the view of the world were now firmly part of an island outlook. France, meanwhile, was richer and more powerful than ever before and ready to expand its interests on the Continent, notably in Italy.

Finally, the war created enduring national heroes who continue to be celebrated today in popular culture. In England, Henry V became a legend in his own lifetime after his stunning victory at the 1415 CE Battle of Agincourt against enormous odds and, thanks to writers such as William Shakespeare (1564-1616 CE), his star has risen only ever higher as Henry V continues to be performed, filmed, and quoted. In France, Joan of Arc became the great figure of the conflict as her heavenly visions inspired her to lift the siege of Orleans in 1429 CE, turning the tide of the war. Joan was burnt at the stake as a witch but, made a saint in 1920 CE, she still today symbolises defiance against the odds and French patriotism. Both countries, then, have created a mythology of the Hundred Years' War, a now long-past time where the enemy was clear, the heroes were virtuous and the victories golden.