The coronation ceremony of the British monarchy as we know it today involves many elements that have been a part of the pageantry ever since the 11th century. Such features of the ceremony carried out in Westminster Abbey since 1066 have been maintained by successive monarchs right down to Queen Elizabeth II (r. 1952-2022) and her coronation on 2 June 1953, as all rulers were keen to show they were part of a long-standing tradition.

The essential purpose of the British coronation ceremony is to see the monarch swear an oath to uphold the Church and rule with honour, wisdom and mercy. The monarch is anointed with holy oil and given a sword, orb, ring, sceptre and, finally, a crown. Then all the nobles and clergy present swear loyalty to their sovereign. The new monarch next embarks on a procession to be presented to the people and finally - although nowadays it has gone out of fashion - there was a great feast of celebration, a function now replaced by live television.

Origins

The earliest English coronation that is recorded in detail, although it was certainly not the first, is the crowning of the Anglo-Saxon king Edgar (r. 959-975 CE) in Bath in 953 CE. Early English kings may even have settled for an ornate helmet rather than a crown but with the arrival of William the Conqueror (r. 1066-1087 CE), a tradition began of holding a lavish coronation ceremony at Westminster Abbey. William was himself crowned there on Christmas Day 1066 CE. Subsequent kings and queens, all keen to maintain a link with history and emphasise their legitimacy for the role, repeated many of the ceremonial elements which are still a part of the coronation ceremony today. Each monarch would add a little something to the ceremony, but in its essentials, a combination of religious and secular rituals, it has remained unchanged for a thousand years.

The Ceremony

In the Middle Ages, monarchs prepared for their big day by bathing, a ritual act of purification conducted on the eve of the coronation in the Tower of London. This was followed by a vigil in the Tower's chapel. Both of these acts were typical of the process by which a squire became a medieval knight. A tradition also began in 1399 CE where the monarch invested a number of new knights on the coronation eve, who became known as the Knights of Bath (and from 1725 CE, members of the order of that name).

The first public act of the coronation spectacle was the procession which took the monarch to Westminster Abbey and allowed as many people as possible to view the proceedings. The star of the show wore red parliamentary robes at this point while musicians and flag-bearers accompanied the main carriage from the Tower of London (or Buckingham Palace in more modern times) to its final destination. From 1685 CE, the procession started closer to Westminster Abbey. On arrival, a group of dignitaries follow the monarch bearing the various precious objects from the British Crown Jewels which will be used later during the ceremony. A bodyguard of sergeants-at-arms, each member of which carries a ceremonial mace (a reminder that protection was their primary aim), then escorts the monarch up the aisle of the Abbey.

Trumpets blare and drums beat as a line of dignitaries follows their monarch to a podium, three of them bearing a sword each. These swords are the Sword of Temporal Justice, Sword of Spiritual Justice, and the blunt Sword of Mercy (aka 'Curtana'); all are survivors of the destruction of the Crown Jewels in 1649 CE (see below). Music has always played an important role in coronations with some pieces being a permanent fixture such as George Frideric Handel's Zadok the Priest, played at all ceremonies since 1727 CE. The congregation then shouts their acceptance and loyalty to the monarch who now wears magnificent robes of silk and gold. The robe worn by Elizabeth II is the golden Imperial Mantle, and she also wore a stole embroidered with symbols of the British nations and plants from the Commonwealth. The monarch is now seated on the chair known as King Edward's Chair, made c. 1300 CE, and the audience settles down for the ceremony to begin proper.

Anointing the Monarch

Another item which survives from the pre-1649 CE regalia is the coronation spoon. This is used to anoint the monarch with holy oil at the start of the ceremony. As the monarch is regarded as chosen by God to rule, their coronation ceremony had several features similar to the consecration of a bishop. In this case, the anointing is done by the Archbishop of Canterbury, who pours a small quantity of oil onto the monarch's head, chest, and palms.

The oil used at the coronation of Henry IV of England (r. 1399-1413 CE) in 1399 CE was believed to have been miraculously given to the Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Becket (in office 1162-1170 CE) by the Virgin Mary. This wondrous oil had only recently been discovered hidden away in one of the darker corners of the Tower of London's cellars. The oil, whatever its real origin, was a useful add-on in Henry's search to legitimise his usurpation of the throne from Richard II of England (r. 1377-1399 CE). Despite Henry IV's best-laid plans, his coronation did suffer a mishap when he dropped the gold coin which he was supposed to ceremoniously offer to God. The coin rolled away and was never seen again, an ill omen of the rebellions that would ruin his reign. Nevertheless, Becket's sacred oil was used at several coronations thereafter.

Symbols of Power

As traditionally a monarch was also a knight, the coronation ceremony involves symbols associated with that rank such as golden spurs, armills (bracelets), and a sword. The two swords which are presented to the monarch at coronations are the Sword of State, which dates to 1678 CE, and the Jewelled Sword of Offering, which was first used by George IV of England (r. 1820-1830 CE) for his coronation in 1821 CE. The archbishop presents these swords and proclaims the following:

With the sword do justice, stop the growth of iniquity, protect the holy Church of God, help and defend widows and orphans, restore the things that are gone to decay, maintain the things that are restored, punish and reform what is amiss, and confirm what is in good order.

(Holmes, 5)

The monarch is then given the Sovereign's Orb which is topped by a cross and so symbolic of the Christian monarch's domination of the secular world. It is placed in the sovereign's left hand. The hollow gold orb, set with pearls, precious stones and a large amethyst beneath the cross, was made in 1661 CE and has been used in every coronation since then.

The monarch is next given the 'Ring of Kingly Dignity', placed on their third finger of the left hand (where a wedding ring is traditionally worn). The one used today, the Sovereign's Ring, was originally made in 1831 CE for William IV of England (r. 1830-1837 CE) and has a cross of Saint George (patron saint of England) in rubies (thought to represent dignity) against a blue background of a single sapphire. A mix-up during the coronation of Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901 CE) resulted in the ring being too tight and the queen later wrote that the archbishop had great trouble putting it on and she removing it later.

The monarch is now given a sceptre and staff or rod, traditional symbols of royal power and justice. The Sovereign's Sceptre (aka King's Sceptre) was first made in 1685 CE, with modifications being added subsequently. Today, it has the 530-carat Cullinan I diamond, also known as the First Star of Africa, sparkling at the top of it.

Crowning Moment

The climax of the entire ceremony is, of course, the actual crowning of the seated monarch. The crown used is usually Saint Edward's Crown (and if an alternative is used, it still carries this name). The crown is named after Edward the Confessor (r. 1042-1066 CE) and was made when Henry III of England (r. 1216-1272 CE), a fan of the saint, fancied new regalia for his coronation. It is likely that parts of a more ancient Anglo-Saxon gold crown were incorporated into this new version. Unfortunately, most of the British Crown Jewels, including the crown, were destroyed, broken up or sold off in 1649 CE following the execution of Charles I of England (r. 1600-1649 CE) and the (what turned out to be) temporary abolishment of the monarchy.

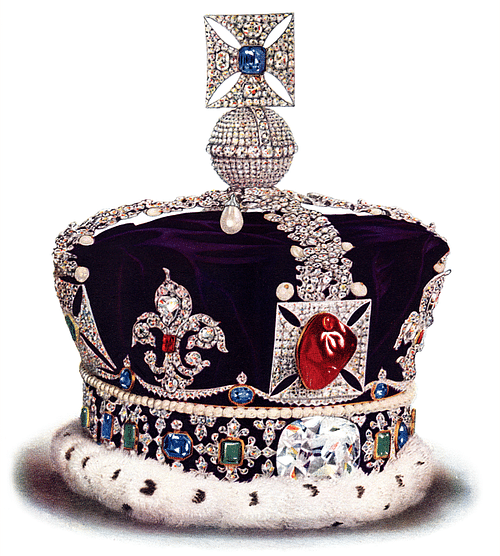

The 1660 CE Restoration of the monarchy necessitated the production of new regalia which would be put into immediate use at the coronation of Charles II of England in 1661 CE (r. 1660-1685 CE). Although it is not clear exactly by what means they were found or reacquired, many of the precious stones that survived the old regalia were incorporated into the new Crown Jewels of the 17th century CE and the new St. Edward's Crown. It is this crown which has been used in coronations ever since. It is gold and weighs 2.3 kilos (5 lbs). As the crown is so heavy, after the actual crowning it is usually replaced by another lighter crown such as the Imperial State Crown. Curiously, the St. Edward's Crown was only ever filled with hired gems when it was needed for a coronation and not until 1911 CE did it receive permanent settings.

The Imperial State Crown was created for the coronation of Queen Victoria in 1838 CE as a lighter alternative to St. Edward's Crown. It is a spectacular crown and contains over 2,800 diamonds, 17 sapphires, 11 emeralds, four rubies, and 269 pearls. Amongst these are the central Black Prince's Ruby (actually a balas or spinel), below it the 317-carat Cullinan II diamond (aka Second Star of Africa), as well as the 104-carat oval-cut Stuart Sapphire and Saint Edward's Sapphire (set in the top cross). The latter sapphire, an octagonal rose cut stone, is said to have been taken from the ring of Edward the Confessor making it the oldest item in all of the Crown Jewels.

Finally, the monarch's consort also receives a crown during the ceremony. The most famous of these today is the Crown of Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. Made of platinum in 1937 CE, it contains the 105.60-carat Koh-i-Noor diamond from India, given to Queen Victoria as part of the peace treaty which ended the Anglo-Sikh Wars (1845-49 CE). The great diamond is said to bring luck to a female wearer and bad luck to a male one, hence it has only appeared in various Queen consort crowns.

The final dramatic act in this royal drama involves the monarch's nobles paying homage and swearing allegiance to their sovereign. Everyone dons their own crowns and coronets if they have the right to wear them and the whole congregation acclaims their new monarch by shouting 'God Save the King/Queen'. The bells of Westminster Abbey ring out and there is simultaneously a 62-gun salute from the Tower of London. The monarch moves to sit on a throne on a raised platform and then receives homage from certain high-ranking clergy and nobles who kiss their hand. Finally, the monarch may issue a general pardon of those found guilty of wrong-doing under their predecessor and sometimes throws coins or medals into the assembly.

Procession

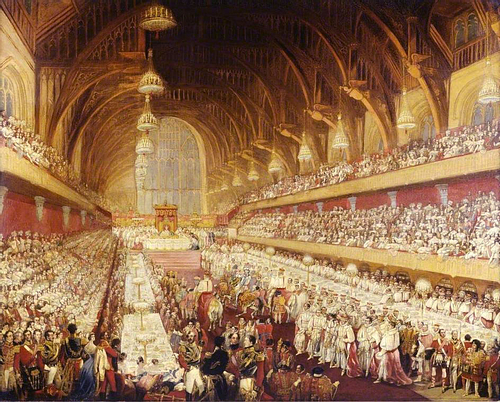

The monarch then leaves Westminster Abbey, now wearing purple imperial robes, and is transported in a golden carriage through the streets so that they may be presented to their people. Finally, the monarch arrives at Westminster Hall where a great feast used to be held. A fixture of medieval coronations, these were an opportunity for a monarch to shower some grace and favour on their most important subjects. Medieval coronation feasts could be huge affairs with up to 5,000 dishes served. We know that the guests at the coronation feast of Edward II of England (r. 1307-1327 CE) in 1308 CE managed to down 1,000 casks of wine. Exotic dishes were prepared and often sculpted into weird and wonderful forms, all served on solid gold dishes, chalices, wine fountains, punch bowls and salt cellars for the added entertainment of the guests. When it was all over, the commoners were allowed in to eat the leftovers. The last coronation feast was held in 1821 CE.

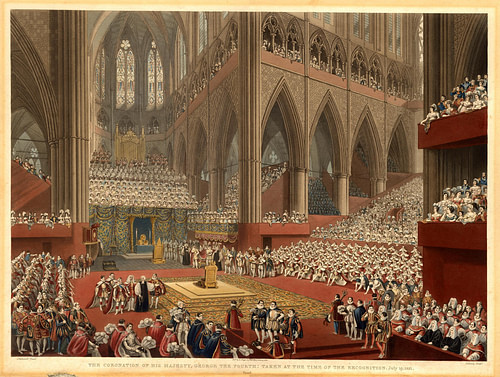

Instead of feasts we now have live television. In the mid-20th century CE, the coronation of Elizabeth II ignited the imagination of a nation. The ceremony was watched by some 20 million people and for the vast majority of them, it was the first event they ever watched on television. One can imagine the next coronation will be live-streamed around the world giving a view better than the people in Westminster Abbey itself with its notoriously bad sightlines. As the famed diarist Samuel Pepys (1633-1703 CE) noted on Charles II's coronation in 1661 CE: "I sat from past 4 until 11 before the King came in…the King passed through all the ceremonies of the Coronation, which to my great grief I and most in the Abbey could not see" (Dixon-Smith, 46). Fortunately, with ever superior camera technology we can look forward to a superb throne-side view of the next coronation, whenever that may be.