The Plague of Athens (429-426 BCE) struck the city, most likely, in 430 BCE before it was recognized as an epidemic and, before it was done, had claimed between 75,000-100,000 lives. Modern-day scholars believe it was most likely an outbreak of smallpox or typhus, but bubonic plague is still considered a possibility.

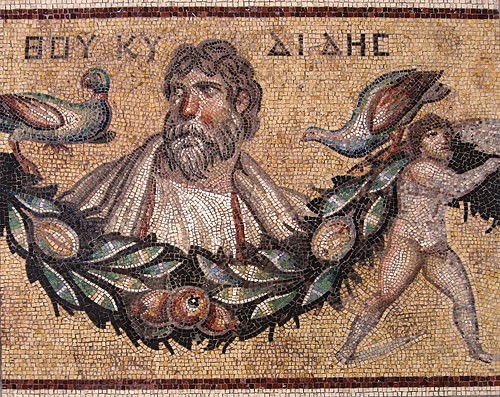

The primary source for information on the event is the historian Thucydides (l. 460/455-399/398 BCE), an Athenian who suffered through the disease and survived. He referred to the pestilence as the plague but this designation was used in antiquity for any widespread outbreak of disease. Many scholars discount the possibility that the event was bubonic plague because Thucydides never mentions buboes (growths) appearing in the groin, armpits, and around the ears which are standard symptoms accompanying bubonic plague as it attacks the lymphatic system and produces these types of swellings.

As the buboes present with a black discoloration, it is these growths which gave the famous pandemic of the 14th century CE the name Black Death. Even so, the possibility that the Plague of Athens was bubonic plague has not been completely ruled out even though the symptoms Thucydides describes seem to align more closely with smallpox. Whatever the disease was, it moved quickly through the population of Athens, killing a great number of people very quickly, before it disappeared in its own time. Thucydides makes the point clearly that there was nothing any human agency could do to stop its spread and ends his narrative by simply saying that it left Athens in a state of misfortune.

Background to the Plague

The plague arrived in Athens through the port at Piraeus shortly after the beginning of the Second Peloponnesian War (431-404 BCE) fought between Athens and Sparta. Tensions between the two city-states had increased after the defeat of the Persian invasion of Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE) in 479 BCE. Although the Greeks had been victorious in the Persian wars, they feared Xerxes I might launch another invasion and so Athenian leaders, headed by the general and statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE), formed the Delian League to prepare a defense for this possibility as well as help liberate fellow Greeks they felt were held under Persian tyranny.

The Delian League became increasingly powerful and seemed to many of the time to primarily benefit Athens. The Athenian fleet developed quickly and Pericles ordered walls erected around the city and monuments, temples, and public buildings which proclaimed the city's wealth and status. The Spartans feared that Athens was becoming too powerful and, because of the wealth generated from the actions of the Delian League, could buy alliances from various other city-states. The First Peloponnesian War (c. 460-446 BCE) was fought primarily between Athens and Corinth (an ally of Sparta) but the second would be a direct conflict between the two antagonists.

At the time the plague struck, the war was escalating and Pericles had ordered the people to withdraw behind Athens' newly-built walls. In doing so, he unintentionally created the perfect atmosphere for the plague to find a home and move swiftly through the population.

Thucydides' Narrative

Thucydides' narrative begins at this point and he notes how, when the plague started, the people of the port city of Piraeus (just outside Athens and the Athenian's central port for trade) believed “the Peloponnesians” (Spartans) had poisoned the wells as part of their war effort. Thucydides wrote his description of the plague as part of his narrative, History of the Peloponnesian War, and included the section, as he says, for “people to study in case it should ever attack again, to equip themselves with foreknowledge so that they shall not fail to recognize it” (Grant, 77). Scholar Michael Grant explains Thucydides' intention and final goal for writing his history:

Thucydides differs from Herodotus, who from time to time displayed a moral, didactic, viewpoint, in that he continuously and deliberately intended to be instructive. He was writing his history, he said, “as a possession forever,” in order to provide “a clear record” of what had happened in the past and will, in due course, tend to be repeated with some degree of similarity (I.22). Thus, Thucydides' work amounted to a social scientist's effort to make general, fundamental, principles emerge from particular actions in order to ensure that knowledge of the past form an effective guide to the future. (63)

The Plague of Athens is treated by Thucydides in the same way as the war with careful attention to the recording of empirical detail without suggesting any reasons for the epidemic. His purpose is entirely instructive in the hope that future generations would be able to learn from the lessons of the past.

The Text

The following narrative comes from the History of the Peloponnesian War, II.vii.3-54 as translated by scholar P. J. Rhodes and given by Michael Grant in his Readings in the Classical Historians:

[The plague] is said to have broken out previously in many other places, in the region of Lemnos and elsewhere, but there was no previous record of so great a pestilence and destruction of human life. The doctors were unable to cope, since they were treating the disease for the first time and in ignorance: indeed, the more they came into contact with sufferers, the more liable they were to lose their own lives. No other device of men was any help. Moreover, supplication at sanctuaries, resort to divination, and the like were all unavailing. In the end, people were overwhelmed by the disaster and abandoned efforts against it.

The plague is said to have come first of all from Ethiopia beyond Egypt and from there it fell on Egypt and Libya and on much of the [other] lands. It struck the city of Athens suddenly. People in the Piraeus caught it first, and so, since there were not yet any fountains there, they actually alleged that the Peloponnesians had put poison in the wells. Afterwards, it arrived in the upper city too, and then deaths started to occur on a much larger scale. Everyone, whether doctor or layman, may say from his own experience what the origin of it is likely to have been, and what causes he thinks had the power to bring about so great a change. I shall give a statement of what it was like, which people can study in case it should ever attack again, to equip themselves with foreknowledge so that they shall not fail to recognize it. I can give this account because I both suffered the disease myself and saw other victims of it.

It was universally agreed that this particular year was exceptionally free from disease as far as other afflictions were concerned. If people did first suffer from other illnesses, all ended in this. Others were caught with no warning, but suddenly, when they were in good health. The disease began with a strong fever in the head and reddening and burning in the eyes; the first internal symptoms were that the throat and tongue became bloody and the breath unnatural and malodorous. This was followed by sneezing and hoarseness, and in a short time the affliction descended to the chest, producing violent coughing. When it became established in the heart, it convulsed that and produced every kind of evacuation of bile known to the doctors, accompanied by great discomfort. Most victims then suffered from empty retching, which induced violent convulsion: they abated after this for some sufferers, but only much later for others.

The exterior of the body was not particularly hot to the touch or yellow, but was reddish, livid, and burst out in small blisters and sores. But inside the burning was so strong that the victims could not bear to put on even the lightest clothes and linens, but had to go naked, and gained the greatest relief by plunging into cold water. Many who had no one to keep watch on them even plunged into wells, under the pressure of insatiable thirst; but it made no difference whether they drank a large quantity or a small. Throughout the course of the disease, people suffered from sleeplessness and inability to rest. For as long as the disease was raging, the body did not waste away, but held out unexpectedly against its suffering. Most died about the seventh or the ninth day from the beginning of the internal burning, while they still had some strength. If they escaped then, the disease descended to the belly: there violent ulceration and totally fluid diarrhea occurred, and most people then died from the weakness caused by that.

The disease worked it way right through the body from the top, beginning with the affliction which first settled in the head. If anyone survived the worst symptoms, the disease left its mark by catching his extremities. It attacked the privy parts, and the fingers and toes, and many people survived but lost these, while others lost their eyes. Others, on first recovering, suffered a total loss of memory, and were unable to recognize themselves and their relatives.

The nature of the disease was beyond description, and the sufferings that it brought to each victim were greater than human nature can bear. There is one particular point in which it showed that it was unlike the usual run of illnesses: the birds and animals which feed on human flesh either kept away from the bodies, although there were many unburied, or if they did taste them it proved fatal. To confirm this, there was an evident shortage of birds of that kind, which were not to be seen either near the victims or anywhere else. What happened was particularly noticeable in the case of dogs, since they live with human beings.

Apart from the various unusual features in the different effects which it had on different people, that was the general nature of the disease. None of the other common afflictions occurred at that time; or any that did ended in this.

Some victims were neglected and died; others died despite a great deal of care. There was not a single remedy, you might say, which ought to be applied to give relief, for what helped one sufferer harmed another. No kind of constitution, whether strong or weak, proved sufficient against the plague, but it killed off all, whatever regime was used to care for them. The most terrifying aspect of the whole affliction was the despair which resulted when someone realized that he had the disease: people immediately lost hope, and so through their attitude of mind were much more likely to let themselves go and not hold out. In addition, one person caught the disease through caring for another, and so they died like sheep: this was the greatest cause of loss of life. If people were afraid and unwilling to go near to others, they died in isolation, and many houses lost all their occupants through the lack of anyone to care for them. Those who did go near to others died, especially those with any claim to virtue, who from a sense of honor did not spare themselves in going to visit their friends, persisting when in the end even the members of the family were overcome by the scale of the disaster and gave up their dirges for the dead.

Those who had come through the disease had the greatest pity for the suffering and dying, since they had previous experience of it and were now feeling confident for themselves, as the disease did not attack the same person a second time, or at any rate not fatally. Those who recovered were congratulated by the others, and in their immediate elation cherished the vain hope that for the future they would be immune to death from any other disease.

The distress was aggravated by the migration from the country into the city, especially in the case of those who had themselves made the move. There were no houses for them, so they had to live in stifling huts in the hot season of the year, and destruction raged unchecked. The bodies of the dead and dying were piled on one another and people at the point of death reeled about the streets and around all the springs in their passion to find water. The sanctuaries in which people were camping were filled with corpses, as deaths took place even there: the disaster was overpowering, and as people did not know what would become of them, they tended to neglect the sacred and the secular alike. All the funeral customs which had previously been observed were thrown into confusion and the dead were buried in any way possible. Many who lacked friends, because so many had died before them, turned to shameless forms of disposal: some would put their own dead on someone else's pyre, and set light to it before those who had prepared it could do so themselves; others threw the body they were carrying on to the top of another's pyre when it was already alight, and slipped away.

In other respects, too, the plague marked the beginning of a decline to greater lawlessness in the city. People were more willing to dare to do things which they would not previously have admitted to enjoying, when they saw the sudden changes of fortune, as some who were prosperous suddenly died, and their property was immediately acquired by others who had previously been destitute. So they thought it reasonable to concentrate on immediate profit and pleasure, believing that their bodies and their possessions alike would be short-lived. No one was willing to persevere in struggling for what was considered an honorable result, since he could not be sure that he would not perish before he achieved it. What was pleasant in the short term, and what was in any way conducive to that, came to be accepted as honorable and useful. No fear of the gods or law of men had any restraining power, since it was judged to make no difference whether one was pious or not as all alike could be seen dying. No one expected to live long enough to have to pay the penalty for his misdeeds: people tended much more to think that a sentence already decided was hanging over them, and that before it was executed, they might reasonably get some enjoyment out of life.

So the Athenians had fallen into the great misfortune and were being ground down by it, with people dying inside the city and the land being laid waste outside. (II.vii.3-54)

Conclusion

Thucydides' reference to the “land being laid waste outside” refers not only to the progress of the plague beyond the city's walls but the ongoing war with Sparta. Sparta, actually, withdrew from their planned assault on Athens because of the plague but continued their war efforts elsewhere.

When the plague left Athens, among the many citizens lost, it also took Pericles who had guided the city through the First Peloponnesian War, enriched it through the Delian League, and adorned it with such lasting monuments as the Acropolis and its Parthenon which he commissioned in 447 BCE. He also encouraged the development of the arts and Greek science in the city as well as the works of notable philosophers such as Protagoras (l. c. 480-430 BCE), Zeno of Elea (l. c. 465 BCE), and one of his close friends, Anaxagoras (l. c. 500 - c. 428 BCE) as well as the careers of doctors such as Hippocrates and Greek tragedy playwrights of the stature of Sophocles.

The loss of Pericles' leadership, along with so many of its citizens, threw Athens off balance and they would eventually lose the Second Peloponnesian War to Sparta and become subject to its dictates. The plague was a decisive factor, not only in the war but in the development of the city, and would influence the history of Athens for many years after it had moved on from the region.