The Arthashastra (or Arthaśāstra) is one of the oldest surviving treatises on statecraft. There is considerable debate about the dating and authorship of the text; it underwent compilation, recension, and redaction several times over the centuries and is likely to have been a witness of religious and ideological transformations, political and socio-economic changes. As a śāstra, it purports to be authoritative and comprehensive and treats its knowledge as eternal, unchanging, and universally applicable. Many scholars have examined the text as the “science of politics” whereas others have seen it as the “science of political economy”, “the science of material gain” etc. Thomas Trautmann described it as the science of running a state, where kingship is identified with wealth. The text itself explains various meanings of the word 'artha'- as the source of livelihood, the earth inhabited by human beings, and the means of protection and acquisition of the earth.

Later texts draw significantly on the Arthashastra. The author of the Kamandakiya Nitisara offers salutation to the author of the Arthashastra for compiling the nītiśāstras and relies so heavily on it that scholars have often described it as a “summary of the Arthashastra”. Some historians point out that this Nitisara focuses more on foreign policy and warfare and excludes the parts on administration and law. It is believed that the latter text was meant to be used by kings who could not manage to read the Arthashastra as they were preoccupied with the affairs of the state. There is also a Tamil text, Tirukkural, possibly from the 4th-5th century CE, that owes a lot to the Arthashastra.

Content

We must remember that Kauṭilya's Arthashastra does not provide us with a clear picture of social constitution, economic elements, or political developments. The primary concern of the text is the working of a state with the king at the apex. Hence, our reconstruction would be bound by the depiction of the state and its association with other aspects of society.

The 15 books of the Arthashastra revolve around one central figure - the king. Be it controlling the production of a wide range of goods, laying down rules for leisure activities, or prescribing food ration for every individual, Kauṭilya left no stones unturned to bring every possible aspect of the state and the lives of its subjects under the ambit of the king's control. He warns that without a king there will be matsyanyāya (Law of the Fish) that is weaker beings are devoured by stronger ones and hence a state cannot afford to be kingless.

The Arthashastra puts forward the saptanga theory of the state being comprised of seven constituent elements:

- the king

- ministers

- countryside

- fort

- treasury

- army

- ally

The pre-eminence of the king perhaps stemmed from the fact that he has the power to acquire and protect productive territory and tax the people living in it. Kauṭilya advises the king to use daṇḍa (punishment) neither too harshly nor too leniently in order to be honoured. The Arthashastra speaks about a wide range of topics and as if putting together a “textbook for kings”, it elucidates on almost all possible aspects that one can think of, such as:

- the training of a prince

- recruiting and appointing officials

- resolving public disputes

- pursuing criminals

- maintaining troops and spies

- conquering areas by defeating other kings.

Economy

The economic landscape of the Arthashastra is agriculture-centred. We find not just methods of agricultural expansion and details of taxation but considerable information about the granary, the storehouse of forest products, the armoury, and most importantly the treasury of the state and an overseer appointed to look after each of them. It must be noted that Kauṭilya showed grave concern about the kośa or treasury (and emphasized upon the means of the accumulation of wealth throughout the text) as he believed that the wealth determined the undertakings by the king and in turn the welfare of the state.

Society

Kauṭilya speaks at length about the king and the ministers of the state but several other working classes are also talked about. Let us look at two groups that find mention in the text but have hardly ever received limelight in this treatise or other historical accounts. The Arthaśāstra contains data on women from various backgrounds. Skilled artisans, spies of the state, female slaves, prostitutes, farmers earned their livelihood and paid taxes to the state. Prostitution was seen as an occupation and several categories of prostitutes are mentioned in the text. There were officials appointed to look into the affairs involved in these professions and the institutions that aided their smooth working. Suvira Jaiswal argues that Megasthenes' account of female bodyguards protecting the king was confirmed by Kauṭilya as the king's bed was surrounded by a troop of women archers. With the tendency of the text to control all aspects of the state and the lives of the subjects, it lays down rules of marriage, divorce and inheritance of property, punishments and crimes against and by women. Thus, the text may not tell us the perspective of women but in many ways gives us a glimpse into the variety of female experiences during that period.

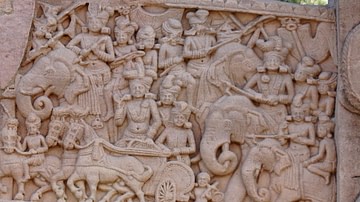

Foreign Policy & War

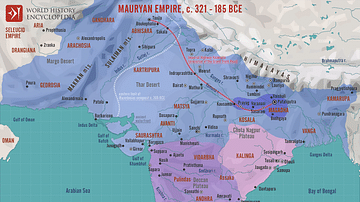

Intricately related to the expansion of the state is Kauṭilya's perception of ancient Indian warfare. His theory of warfare comprised of a set of rigid principles which could guarantee success. Kauṭilya is concerned not just by the war between states but also the intra-state wars or the rise of rebellions. He suggests extra taxation during emergencies but warns against it in the long run as he perceives internal security depends on the contentment of the subjects.

Kauṭilya lays down six measures of foreign policy in the 7th book and elucidates in the conduct of each:

- peace

- war

- staying quiet

- marching

- seeking shelter

- dual policy.

He advises that during decline one must try to make peace and when prospering, one should make war and provides techniques to deal with weaker, equal and stronger kings. He gives the theory of the circle of kings and recognizing friendly and unfriendly elements so that the king may bring regions under his rule and become the sovereign of the “four corners of the earth”.

Arthashastra & Dharmahastra

The intertextuality between Manu's Manava Dharmashastra and the Arthashastra of Kauṭilya has been studied by several scholars who have taken up the daunting task of analysing the style, structure, and contents of both these texts to understand their relations and contradictions and most importantly to reconstruct a picture of the society then. Many scholars argue that some sections of the Arthashastra are older than Manu's text by citing the presence of not just parallel texts but a common and unusual vocabulary. Olivelle has also argued that unlike the Arthashastra, the Manava Dharmashastra was written by a single individual who borrowed heavily from the Arthashastra's material on king, government, law and judiciary, but integrated the material into his own organizational scheme, presenting a unique text within the literary tradition of Dharmashastras. There is also a structural similarity between the seventh chapter of Manu and the Arthashastra.

Wendy Doniger brings forth the contradiction that underlies the Arthashastra and the laws of Manu and highlights the subtle subversion of dharma by the Arthashastra. She explains that ideas from Manu were stitched into Arthashastra often leading to a pro-Brahmanic and pro-dharmic revision of the text. She cites examples like the difference in the harshness of punishment for the verbal abuse of Brahmins according to the Manava Dharmashastra and the Arthashastra to show how the latter trod lightly in its critique of dharma. Doniger argues that this pervasive un-dharmic agenda was made possible by coating it with a thin veneer of dharma and disregarding rather than challenging the power of Brahmins.

Regarding the Manava Dharmashastra and Arthashastra, we may ask what was the scope of dissent against dharma in ancient India? Was the world beyond the one that people knew about more important than achieving material well-being in this world or was it the other way round? When two authoritative texts laid down contradicting rules and punishments, which text superseded the other and why? And finally, if we assume that the different members of the priestly class wrote these texts and the monarchs read them carefully, to what extent were the common men and women (possibly illiterate) affected by what was laid down in these treatises?