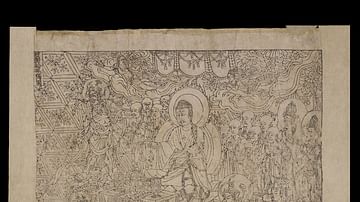

The Upanishads are among the best-known philosophical-religious works in the world and also among the oldest as the earliest texts are thought to have been composed between 800-500 BCE. These works are philosophical dialogues relating to the concepts expressed by the Vedas, the central scriptures of Hinduism. Adherents of Hinduism know the faith as Sanatan Dharma meaning “Eternal Order” or “Eternal Path”, and this order is thought to be revealed through the Vedas whose concepts are believed to be direct knowledge communicated from God.

The word Veda means “knowledge” and the four Vedas are believed to contain the essential knowledge of the universe and how an individual is to live in it. The term Upanishads means to “sit down closely” as if drawing near to listen to some important instruction. The Vedas provide the broad strokes of how the universe works and how one is to respond; the Upanishads then give instruction on the specifics of an individual's response.

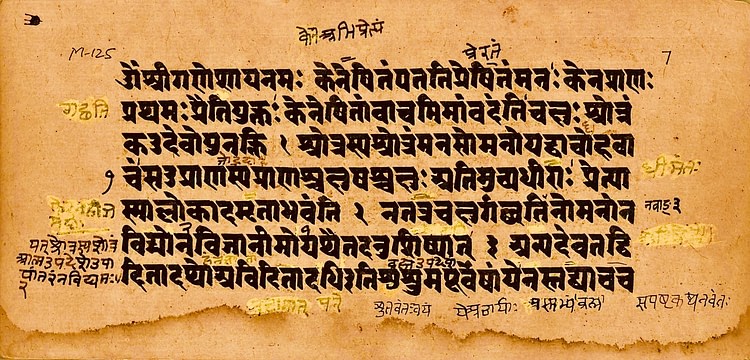

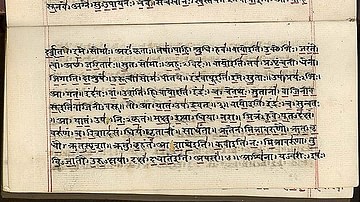

The Upanishads are referred to as Vedanta – “the end of the Vedas” – in that they complete the sacred revelation received by the sages at some point in the ancient past. The Vedas are considered Shruti (“what is heard”) in that they were received by sages in a deeply meditative state directly from God. They were then preserved in oral tradition until written down between c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE. The Upanishads are also considered by orthodox Hindus as Shruti in that the wisdom and insight they contain appears too profound to have originated in the mind of a human being. There are between 180-200 Upanishads in total but the best known are the 13 which are embedded in the texts of the Vedas.

Vedas & Upanishads

The four Vedas were passed down from generation to generation until they were committed to writing during the so-called Vedic Period between c. 1500 - c. 500 BCE in India. The concepts are generally thought to have originated in Central Asia and arrived in India with the Indo-Aryan Migration of c. 3000 BCE (though this is contested by some scholars). Although some schools of thought claim there are five Vedas, the scholarly consensus rests on four:

- Rig Veda

- Sama Veda

- Yajur Veda

- Atharva Veda

The 13 best-known Upanishads are embedded in the texts of each of these in response to the particular concepts each expresses. The 13 Upanishads are:

- Brhadaranyaka Upanishad

- Chandogya Upanishad

- Taittiriya Upanishad

- Aitareya Upanishad

- Kausitaki Upanishad

- Kena Upanishad

- Katha Upanishad

- Isha Upanishad

- Svetasvatara Upanishad

- Mundaka Upanishad

- Prashna Upanishad

- Maitri Upanishad

- Mandukya Upanishad

The composition of the first six (Brhadaranyaka to Kena) is dated to between c. 800 - c. 500 BCE with the last seven (Katha to Mandukya) dated from after 500 BCE to the 1st century CE. The works take the form of narrative philosophical dialogues in which a seeker approaches a master for instruction in spiritual truth. This seeker may not always know that he or she is seeking such truth and, in some Upanishads, a disembodied voice speaks directly to an audience who then becomes the speaker's interlocutor in the dialogue or, in other words, the seeker.

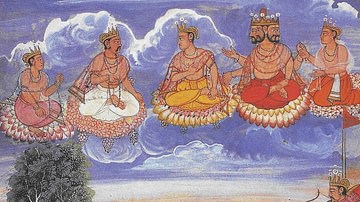

The purpose of the works is to engage an audience directly in spiritual discourse in order to raise one's awareness and assist one in the goal of self-actualization. The Upanishads developed from the religious-philosophical system of Brahmanism which maintained that the creator of the universe, and the universe itself, was a Supreme Over Soul they called Brahman. The majesty and power of Brahman was too great for human beings to apprehend and so It appeared to people through avatars which took the form of the Hindu gods such a Brahma, Vishnu, Shiva, and the many others.

Human beings could recognize in these gods the inherent nature of Brahman but, in order to have a direct experience, they were encouraged to pursue a relationship with their higher self – known as the Atman – which was the spark of the Divine each individual carried within. The purpose of life, then, was to attend to the responsibilities one had been sent to earth to fulfill by recognizing one's duty (dharma) and performing it with right action (karma) as one worked toward self-actualization and liberation (moksha) which freed one from the cycle of rebirth and death (samsara).

Self-actualization is achieved with the understanding of the phrase Tat Tvam Asi – “Thou Art That” meaning one is already that which one wishes to become; one only has to realize it. Each individual already carries the Divine Spark within; recognizing this connects one to God and to other people. This understanding of human existence, basically, informs the belief system of Sanatan Dharma and the Upanishads suggest how one might best live that understanding.

Summary & Commentary

The following 13 Upanishads are presented in the order in which they are believed to have been composed. There is no direct narrative continuation from the first to the last, but all address the same basic concepts, just from different angles.

Brhadaranyaka Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda and the oldest Upanishad. The name means, roughly, “Great Forest Teaching” and it is usually credited to the sage Yajanvalkya (8th century BCE) though this is contested. It begins with the creation of the universe by the god Prajapati who is later identified as an avatar of Brahman. The Atman as the Higher Self, the immortality of the soul, the illusion of duality, and the essential unity of all reality is discussed and explained through the analogy of salt in water:

As a lump of salt thrown in water dissolves and cannot be taken out again, though wherever we taste the water it is salty, even so, the separate self dissolves in the sea of pure consciousness, infinite and immortal. Separateness arises from identifying the Self with the body, which is made up elements; when this physical identification dissolves, there can be no more separate self. (4.12)

The Brhadaranyaka Upanishad is among the most famous, not only for establishing the concept of liberation from the cycle of rebirth and death and union of the Atman with Brahman but through its use by the 20th-century CE poet T.S. Eliot (l. 1888-1965 CE) in his masterpiece The Wasteland.

Chandogya Upanishad: Embedded in the Sama Veda and considered as old as the Brhadaranyaka, though the date of composition is unknown. The text repeats some of the content of the Brhadaranyaka but in metrical form which gives this Upanishad its name from Chanda (poetry/meter). The narratives further develop the concept of Atman-Brahman, the importance of right action in accordance with one's duty, and how the Atman-Brahman connection works.

This is most famously explained in the passage known as The Story of Shevetaketu. Shevetaketu returns home after twelve years of education, arrogant of his knowledge, and is greeted by his father Uddalaka. Uddalaka asks him whether he has learned “the spiritual wisdom which enables one to hear the unheard, think the unthought, and know the unknown” (6.1.3). Shevetaketu has no idea what he is talking about and so Uddalaka leads him through different lessons on unity pointing out how one comes to know the underlying form of all clay from a single piece of clay or all iron from a single piece of iron. The singular is informed by the collective. Each seemingly separate vessel made of clay participates in the totality of the substance of clay. Uddalaka continues through other examples to a discussion of the individual, the Atman, and Brahman, finally leading his son to the realization of Tat Tvam Asi and the unity of all existence.

Taittiriya Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda and also considered one of the older Upanishads. The name may derive from the possible author, the sage Tittiri, but this is challenged. The work begins with benedictions praising Brahman, “source of all power”, and the vow to speak the truth and follow the law before asserting the commitment to learn the Vedas and asking the Divine for the light of wisdom to illuminate one's life and lead one to unity with the Ultimate Reality. The work continues on the theme of unity and proper ritual until its conclusion in praise of the realization that duality is an illusion and everyone is a part of God and of each other.

Aitareya Upanishad: Embedded in the Rig Veda, the Aitareya repeats a number of themes addressed in the first two Upanishads but in a slightly different way. The most notable example is the discussion of the Five Fires of the cycle of human existence: when someone dies, they are cremated (first fire) and then travel as smoke to the other world where they enter storm clouds (second fire) and fall to earth as rain (third fire) to become food eaten by a man (fourth fire) and become semen which enters a woman (fifth fire) to develop into a fetus. The Aitareya emphasizes that this fetus is the Atman of its parents, who guarantees their immortality after its birth and maturity in that they will be remembered but also in the experience of unconditional love. Children and family life, in other words, can provide one with the means of realizing one's connection to God.

Kausitaki Upanishad: Embedded in the Rig Veda, this Upanishad also repeats themes addressed elsewhere but focuses on the unity of existence with an emphasis on the illusion of individuality which causes people to feel separated from one another and isolated from God and the world around them. This concept is summed up in the line, “Who are you?” and the response, “I am you” (1.2). The work concludes with a chant on the importance of knowing the underlying form of existence and not relying on superficial appearances to define what one believes to be true in life.

Kena Upanishad: Embedded in the Sama Veda, the Kena develops themes from the Kausitaki and others with a focus on epistemology and self-knowledge. The Kena rejects the concept of intellectual pursuit of spiritual truth claiming one can only understand Brahman through self-knowledge, through personal, spiritual work, not through other people's experiences or words in books. The basic concept is summed up in the lines:

There is only one way to know the Self, and that is to realize him yourself. The ignorant think the Self can be known by the intellect, but the illumined know he is beyond the duality of the knower and the known. (2.3)

Intellectual pursuits lead to intellectual ends; spiritual truth cannot be apprehended through the work of others, only by one's own efforts.

Katha Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the Katha is another of the best-known Upanishads containing the line used by the British author Somerset Maugham (l. 1874-1965 CE) to inform his bestselling 1944 CE novel The Razor's Edge (“the path to salvation is narrow and difficult to walk as the razor's edge”). The Katha emphasizes the importance of living in the present without worrying about past or future (what the philosopher Ram Dass phrased as “Be Here Now”), examination and explanation of the Atman and its relation to the soul/mind of an individual (in the parable of the chariot), the concept of moksha, vitality of the Vedas and, especially, self-actualization as illustrated in the tale of Nachiketa and Yama, God of Death.

In this story, young Nachiketa and his father argue and Nachiketa's father angrily tells him to go to death. Obedient to his father's will, he does so but there is no one home when he arrives in the underworld. Nachiketa waits outside of the door of death for three days until Yama returns, apologizes for keeping him waiting, and offers him three wishes to make up for his poor hospitality. The boy asks to be able to return safely to his father, to learn the fire sacrifice of immortality and, most importantly, to know what happens after death. Yama agrees to the first but refuses the last, offering Nachiketa anything else, but the boy refuses. Yama's initial refusal turns out to be a test and he is pleased that Nachiketa could not be tempted by worldly pleasures nor distracted from the search for truth. Yama then reveals to Nachiketa the secret of life: there is no death because the soul is immortal and there is no self because all is one. No one is ever alone, nothing is ever finally lost, and everyone – eventually – will return home to God.

Isha Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, the Isha focuses emphatically on unity and the illusion of duality with an emphasis on the importance of performing one's karma in accordance with one's dharma. The major thrust of the piece is on the importance of recognizing the unity of all existence and the folly of believing one's self to be alone in the world. This concept is best expressed in the passage from 1.6:

Those who see all creatures in themselves

And themselves in all creatures know no fear.

Those who see all creatures in themselves

And themselves in all creatures know no grief.

How can the multiplicity of life

Delude the one who sees its unity?

In recognizing the essential oneness of existence, one is liberated from fear, grief, loneliness, bitterness, and other negative emotions. Once freed, one may more easily concentrate on self-actualization.

Svetasvatara Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda. The Svetasvatara was obviously written by a number of different authors at different times and yet maintains a cohesive vision focusing on the First Cause. In some of its opening lines it asks:

What is the cause of the cosmos? Is it Brahman? From where do we come? By what live? Where shall we find peace at last? What power governs the duality of pleasure and pain by which we are driven? (1.1)

The work continues to discuss the relationship between the Atman and Brahman and the importance of self-discipline as the means to self-actualization.

Mundaka Upanishad: Embedded in the Atharva Veda, this Upanishad focuses on personal spiritual knowledge as superior to intellectual/experiential knowledge. As with the other Upanishads, the emphasis is on what lies beneath the veneer of the apprehensible world. The text makes a distinction between higher and lower knowledge with “higher knowledge” defined as self-actualization and “lower knowledge” as any information which comes from an external source, even the Vedas. This is clearly expressed in the lines:

Knowledge is two-fold, higher and lower.

The study of the Vedas, linguistics,

Rituals, astronomy, and all the arts

Can be called lower knowledge. The higher

Is that which lead to Self-realization. (1.3)

Lower knowledge has its place in one's life but should not be confused with one's existential purpose of self-actualization and union with the Divine. The Mundaka is another among the most popular Upanishads for its emphasis on individual effort to achieve the spiritual understanding that there is no such thing as the isolated individual once one realizes that everyone is related on the most fundamental level and all are on the exact same path.

Prashna Upanishad: Embedded in the Atharva Veda, the Prashna concerns itself with the existential nature of the human condition beginning with a discussion of how life begins and continuing to thoughts on immortality while addressing subjects such as what constitutes “life” and the nature of meditation/wisdom. It focuses on devotion, finally, as the means to liberate one's self from the cycle of rebirth and death, as expressed in the passage:

May we hear only what is good for all.

May we see only what is good for all.

May we serve you, Lord of Love, all our life.

May we be used to spread your peace on earth. (1.1.)

This concept of selfless devotion to the deity would inspire the Bhakti (“devotion”) movement of the Middle Ages which would later be revived as the Hare Krishna Movement of the present day. Both of these movements emphasized complete devotion to God as a means of connecting fully with the divine impulse of the Universe.

Maitri Upanishad: Embedded in the Yajur Veda, and also known as the Maitrayaniya Upanishad, this work focuses on the constitution of the soul, the various means by which human beings suffer, and the liberation from suffering through self-actualization. One of the most famous passages discusses the danger of settling for the worship of what one perceives to be (or has been told) are gods instead of seeking God for one's self. Allowing one's self to settle for a “religious” experience instead of a “spiritual” experience cheats one of the chance at a true relationship with the Divine which can only be achieved by individual effort.

Mandukya Upanishad: Embedded in the Athar Veda, this work deals with the spiritual significance of the sacred syllable OM as an expression of the self and essential unity of all things. The work begins with the lines, “OM stands for the supreme reality. It is a symbol for what was, what is, and what shall be. OM represents also what lies beyond past, present, and future” (1.1). The Mandukya also discusses the Four States of Consciousness – Waking, Dreaming, Deep Sleep, and Pure – noting that pure consciousness is the underlying form of the other three. This consciousness may be realized by directing one's focus inward to self-improvement and spiritual exercises which clear the mind of external distractions and illusion.

Conclusion

The above is only a cursory summary of some of the concepts addressed by the Upanishads as each work layers its dialogues on others to encourage deeper and deeper engagement with the text. Shevetaketu's realization of his own divine nature, which twelve years of religious education could not teach him, is only one illustration of the concept of Tat Tvam Asi in the Chandogya Upanishad just as Nachiketa's discourse with the God of Death provides only one exchange in the Katha Upanishad.

One could conceivably spend one's life in study of the Upanishads and, in doing so, it is believed one would progress from a state of spiritual darkness and isolation to the realization that one has never been alone as the true spark of the Divine resides within each soul. Writers, philosophers, scholars, artists, poets, and countless others around the world have responded to these 13 works since they were first translated from Sanskrit beginning in the 17th century CE. From that time to the present, their influence has only grown and today they are recognized as among the greatest spiritual works ever composed.