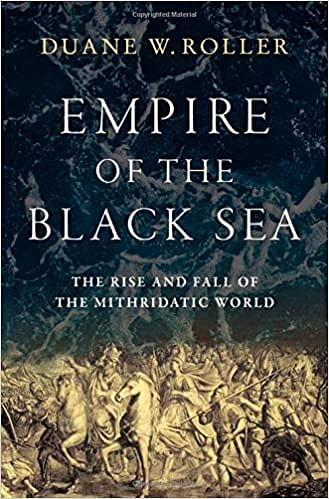

Multiple Fulbright Award-winning Duane Roller joins us to talk about his new book, Empire of the Black Sea. The first thorough analysis in English of the dynasty as a whole, Empire of the Black Sea chronicles each ruler of the Mithridatic kingdom and their complex relationships with the powers of the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East. Roller also explores Pontus' many military successes that helped it to encircle most of the Black Sea at its peak, focusing extensively on the kingdom's three wars against the Roman Republic that eventually led to their demise.

Patrick Goodman (AHE): Thank you very much for offering Ancient History Encyclopedia this interview for your new book, Empire of the Black Sea: The rise and fall of the Mithridatic World. For readers who may not be familiar with the Pontic Kingdom, could you give a brief overview of the age, location, and contemporaries of Pontus?

Duane Roller: Thank you. People have studied Mithridates the Great (Mithridates VI Eupator Dionysius) before, but he is presented in a vacuum. The Pontic Kingdom, which had its origins in the days after Alexander the Great was one of the minor powers of the Hellenistic world. And at least in English, this is the first time that anyone has put together a cultural history of essentially those 250 years from the readjustment of everything after the death of Alexander to the death of Mithridates the Great in 63 BCE.

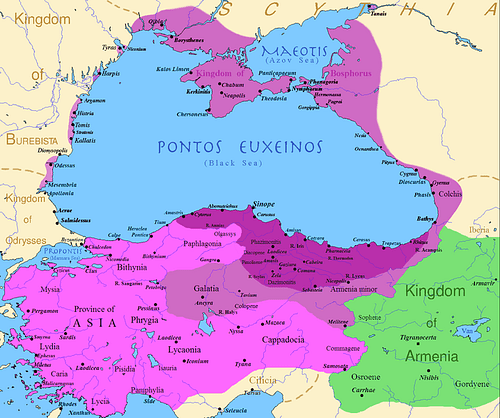

Pontus refers basically to the south coast of the Black Sea. It is in Turkey today, and it is the area from the Bosphorus all the way to the east where the Black Sea begins to curve up north.

The Pontic Kingdom was established in the generation after the death of Alexander the Great - that is the end of the 4th century BCE - when things were very much in flux. Alexander conquered all this territory, left no provisions after the event of his death, and then dropped dead at an early age.

It was one of many such kingdoms that existed in the Hellenistic period - almost always contentious; fluid borders; some more powerful than others. The Pontic Kingdom was not in the first rank, like the kingdom in Egypt, but it was an important second-level kingdom of the Hellenistic period. And like all these kingdoms, it eventually fell to the spread of Rome.

PG: Did the Pontians see themselves as more Greek or Persian?

DR: They probably used what was more advantageous. In the case of the Pontic Kingdom, it is a mixture of Greek and Persian. The name Mithridates is Persian. The Mithridatic kings allegedly were descended from the great kings of the Persian Achaemenid Empire: Darius I and Xerxes and so forth. But as time passed, it became more and more Greek. We can see when we get to coinage, the legends on their coinage were always Greek. And, of course, the depictions on the coinage are in the tradition of Greek sculpture as well. But the Persian heritage was always important because the Persian Empire had been a major power in that part of the world.

There is a certain pragmatism to it all, also. Greek was the great culture of the era. Greek was everybody's second language. Greek was the world of Alexander the Great. So the more Greek you appeared, the more significant your kingdom could be.

PG: And if you could not match the feats of Alexander, you could at least look like him in a statue or coin.

DR: (laughs) Yes, it impacted art as well. There are an awful lot of people who seem to look suspiciously like Alexander in Hellenistic and Roman times. It is the same thing with Cleopatra and Augustus.

PG: Speaking of Cleopatra, you wrote a book in 2010 CE entitled Cleopatra: a Biography. Readers may find it interesting that Cleopatra I was a Pontic princess. Did Cleopatra VII retain connections with her namesake's ancestral home?

DR: Well, it is probable that Cleopatra never went to Pontus, but as one of the last monarchs of the Hellenistic world, she of course was very much aware of the history. She was a highly educated person. With the death of Mithridates the Great, who died just a few years after Cleopatra was born, she inherited many of his ambitions. In fact, there is evidence that people from the court of Mithridates the Great went to Alexandria. So there is this fluidity between kingdoms. When one kingdom bites the dust, the people who are connected to that kingdom find new jobs and go to other kingdoms.

Cleopatra was like Mithridates VI in a number of ways. She was a highly skilled linguist. She wrote on medical topics. And she took up the cause - the futile cause - of stopping the advance of Rome. Which at the time, nobody knew would not happen. We look 2000 years later, and see the advance of Rome as inevitable, but that was probably not the case in the 1st century BCE. So Cleopatra inherited the legacy of Mithridates the Great, who himself inherited the legacy of Hannibal.

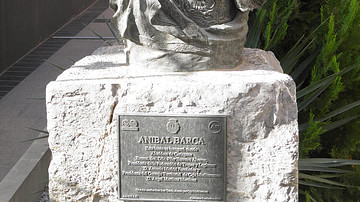

PG: It is interesting that you bring up such a well-known historical figure as Hannibal. How is he connected to the region?

DR: We tend to forget about Hannibal after he was defeated by the Romans, thrown out of Italy, and later Carthage. He came to Asia Minor and tried to stir up opposition to Rome for about 20 years or so. He later died just west of Pontus in the region we call Bithynia. But that provided again another impetus. Hannibal did not do it, so maybe Mithridates VI would be the new person to stop the Romans.

PG: You reference the famous naval engagement between the Hannibal-lead Bithynian forces and Pergamon where he launched pots filled with snakes onto the enemy ships.

DR: (laughs) It becomes very visual when you read it. Even to think of the logistics of it all.

PG: So we now have a Pontic connection with Cleopatra and Hannibal. Who are some of the other famous figures of myth and history readers may find in the Empire of the Black Sea?

DR: Let me just say in passing that people in antiquity did not make the distinction between myth and history that we do. It was all a continuum for them. And the early mythic stories that we think of as Greek mythology were as real to them as the Hellenistic kings.

With that said, I think the most important myth of this area was Jason and the Argonauts. This was the country where the golden fleece was located. And this was very much part of the self-image of the Mithridatic Kings. This connected them to one of the earliest stories of Greek mythology.

PG: The second half of your book focuses on the greatest and last of the Pontic kings, Mithridates VI. There is so much of interest here for readers, could you just begin with a short explanation of how modern historians are able to match his birth to a major celestial event.

DR: Celestial portents are common with the birth of the hero, and go back to mythological times. But the people who study Chinese astronomy - and of course I have to look at all this derivatively - have found out that the 130s BCE was a period of unusual comet activity. The Chinese sources seem to focus on a couple of them that happened exactly around the time that Mithridates was born. So this seems like a case where there actually was some sort of celestial activity at the time.

He also seemingly had this mark on his forehead (from a lightning strike), which Harry Potter also had. J.K. Rowling knew her sources. That was probably a birth defect, which got put into the story about the birth of the great hero.

PG: That is also a part of the story of Dionysos, correct?

DR: Yes, Dionysos' birth story being he was pulled out of Semele as she was consumed by fire after being tricked into seeing Zeus in all his glory. Which evidently is fatal to mortals. And so there is the birth out of fire, which also has a Persian connotation. Fire is very much a Persian theme, which gives Mithridates Persian credentials as well. These people knew what they were doing in creating a public image.

PG: Regarding public image, Mithridates VI was keen on reenforcing his connection with Alexander the Great. How did he use this to further his own ambitions?

DR: I think in Mithridates' idea of fulfilling Alexander's vision of conquering the West. He did not have to conquer the East; Alexander had done that. So this whole idea of going west for Mithridates was “I'm the new Alexander, and I will take on the West.” But instead of Carthage, as it most probably was for Alexander, the West is now Rome.

PG: Which leads us to Pontus vs Rome. Throughout the first war with Rome, Mithridates VI becomes massively popular due to his rapid victories and compassion shown towards defeated enemies. However, these incredible and inspiring underdog victories are quickly punctuated by extreme violence. What in your opinion created this change in Mithridates VI's behavior?

DR: The massacre of the Italians at Ephesus and elsewhere probably was the biggest mistake Mithridates ever made. And though we do have to remember that such things do tend to be exaggerated, it was probably a very violent event. We have enough anecdotes from individuals to lend it a certain credibility.

Obviously Mithridates had the view that if this was done, the Romans would go away and not bother the Greeks anymore. Certainly, there was a heavy amount of abuse by the Roman government in the Province of Asia- that is western Turkey- in tax collecting and things of that nature. This was a big problem in provinces of the late Roman Republic. If you were in charge of a province and ripped it off, then you would be tried in Rome by the very same people who next year would like to try the same thing.

But Mithridates' mistake in this was not realizing that the Romans would just come back in greater force. He thought that if he eliminated the Roman tax collectors, eliminated the Roman officials, that would be the end of it. That if you solve one problem, you solve all problems.

But even if we reduce the numbers, as one always should, it still is a very bad strategic error on his part. And probably the beginning of the decline of his fortune, because he could no longer argue in a global sense that he was the savior of the world.

PG: One of my favorite parts is a fascinating exchange between Mithridates VI and the Roman general Marius. How did you come across this small scene in history, and what other primary sources did you consult in writing the Empire of the Black Sea?

DR: Well, it is all there in the literature. You just have to ferret it out. The story of Marius has a bit of a formula about it, and only makes sense in projecting what Alexander said about the Romans, which may not be true. It then becomes a nice theme to carry from Alexander down to Mithridates.

Insofar as sources are concerned, we have a lot about Mithridates VI. There is a historian named Appian who wrote about 100 CE and wrote a history of the Mithridatic Kingdom, which focuses mostly on that last Mithridates but gives us the most information about the earlier kings. And then we have various biographies of Plutarch at about the same time. We have the lives of Lucullus, Sulla, Marius, and Pompey, the Romans who are most connected with Mithridates. So there is a fair amount on Mithridates. Believe it or not, there is more written on Mithridates than there is on Cleopatra.

If Mithridates had any memoirs, we have no trace of them. So we try to put it all together. We try to remember that points of view change and can become anachronistic in trying to come up with a decent picture of the hero. But as a historian, we just put it all together and come up with some reasonable idea of what might have happened.

PG: Prof. Roller, thank you so much for your time, and congratulations on the publication of the Empire of the Black Sea. What is next for you?

DR: I am working at the moment on things involving ancient geographers. We have a lot of geographical texts that have not been properly vetted or translated.

Also, I have not decided on a new biography of Herod the Great. He has been written about a great deal, but mostly from the religious side of his career, not his Hellenistic side. I might proceed with that, but I have not decided yet.

Duane W. Roller is Professor Emeritus of Classics at The Ohio State University and the author of numerous books, including Cleopatra: A Biography, Cleopatra's Daughter: And Other Royal Women of the Augustan Era, and Ancient Geography.