Dr. Jeanne Reames' Dancing with the Lion: Becoming and Dancing with the Lion: Rise follow an epic tale of Alexander before he was “The Great.” In this interview, Dylan Campbell inquires about her passion for history and the development of her new novels.

DC: To start, what first got you interested in Alexander the Great and Macedonia, and what has kept you passionate and motivated within this field?

JR: While doing my MA at Candler School at Emory University, several professors kept mentioning this dude, Alexander the Great, as if everybody knew who he was. I did not have a clue. That owed to escaping high school and college with no history classes aside from one elective on the Early Church. I thought I hated history because those teaching it had been so bad.

Intrigued by his youth and huge success, I ambled over to the Emory library to grab two bios, one of which had PICTURES! Whoo. They turned out to be N.G.L. Hammond's 1980 CE Alexander the Great: King, Commander, and Statesman (his earlier, more measured bio) and Peter Green's (original 1974 CE Thames & Hudson) Alexander of Macedon.

I could not have picked more divergent views had I tried. I became fascinated by the enigma of who Alexander really was. I also began reading about the country that produced him, ancient Macedon and got to Greece only somewhere down the line. Ergo, I have always looked at Greek history with a northern eye.

What kept me interested? Writing a novel and going on to get a Ph.D. in, of all things, history.

DC: For those who have not had a chance to read your two new novels, Dancing with the Lion: Becoming and Dancing with the Lion: Rise, could you elaborate on the scope of the books and who would be the intended audience?

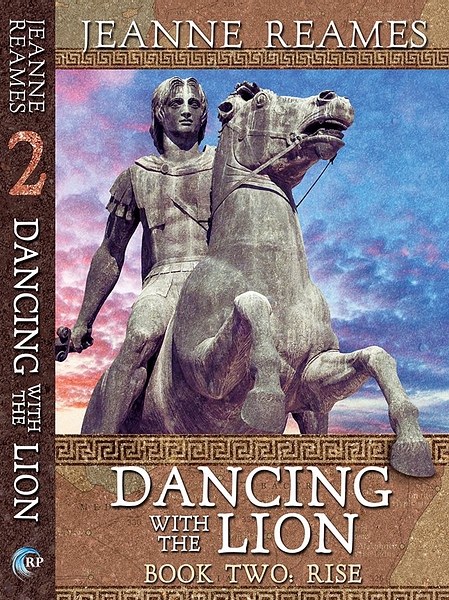

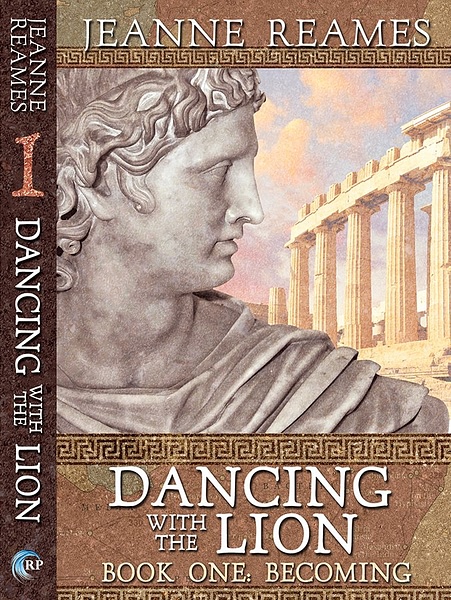

JR: Dancing with the Lion is a coming-of-age historical novel with a touch of magical realism, the story of the young Alexander before he became “the Great.” It covers his life from just before 13 till just after 20. It is really one long book that Riptide divided in half, so ideally, the two should be read back-to-back as one work. (The author's note is at the end of Book Two.)

The first (Becoming) centers on Alexander's time with Aristotle and formation as an individual. Book Two (Rise) begins when Philip II of Macedon makes Alexander regent before leaving to besiege Perinthos, so it turns outward, examining Alexander's growing involvement with larger-world politics.

It is sometimes been mislabeled as YA or gay romance. I embrace the LGBTQI label, but if some romance readers enjoyed it, others did not, depending on what one reads outside that genre. While the friendship and eventual love story between Alexander (Alexandros in the novel) and Hephaestion (Hephaistion) is a significant part, their family relationships (particularly with their fathers) are just as weighty. The books also have plenty of politics and war, especially in Rise, but are primarily about human relationships. I talk a bit about the father-son dynamics in this blog post: “Philippos, Amyntor, and Fathering in Dancing with the Lion.”

That is why I am really happy to do interviews for sites like the Ancient History Encyclopedia, to get the books into the hands of readers fond of ancient-world historical fiction. Much of the original marketing was to romance blogs rather than historical fiction blogs. One tidbit: the books have two different covers each, which has caused some confusion. It is the same text inside but comes with either “statue” covers, or “face” covers. Incidentally, the model for Book Ones's “face” cover is based on the Acropolis head of the 18-year-old Alexander. If purchasing a paper version, readers can choose on Amazon which cover they prefer via editions, and the novels are available in several countries through Amazon.com.

Readers can find both books on Riptide Publishing's website where they can purchase the bundle. Also, the novels can be purchased at Barnes & Nobel and Kobo.

DC: How did you decide to depict their relationship and what factors did you take into consideration? Were there any hesitations to how you wanted certain situations or dialogue to be conveyed within your novel?

JR: This is a novel, which means characterization (and themes) drive it, rather than plot. One theme involves Greek masculinity, so foundational to modern Western ideas of manhood. If ancient Greece accepted same-sex pairings, even saw them as crucial to a young man's development, it was also a highly misogynistic society, continuously policing men who “made themselves like women.” For instance, in Athens, if a citizen male could be convicted of prostitution, it disqualified him from holding public office (see “Against Timarchos” by Aeschines).

Ergo, all these conditions attended male-male relationships, from the relative age and status of the partners, to what physical acts were and were not acceptable. In many ways, the boys' relationship in the novel is pretty typical, but it is also transgressive due to who Alexander is (a prince) and gets more so in Rise. As a novelist, that is really exciting to explore. It lets me dissect their (and our) ideas of proper masculine behavior.

So yes, as noted above, I do depict Alexander and Hephaestion as lovers, although they begin as friends. And it is really friendship that defines the depth of their bond. In Becoming, Hephaestion thinks to himself, they had shared pain; that was a stronger bond than passion.

Rather than digress into a really long spiel about why I decided to read their relationship that way, I will point again to a blog post with more depth: “Alexander, Hephaistion, and the Problem of Our Sources.”

While I realize that making the choice to show them as lovers could discomfort some readers, that is what fiction does. It pulls us in, spins us around, and shows us the world through other eyes. Fiction seeks to enlarge us, pushing us sometimes outside our comfort zones.

DC: Within these novels, Alexander is represented as Alexandros, the young Macedonian man, rather than Alexander. What made you decide to make this distinction?

JR: I am interested in origins. That may be why I like reading coming-of-age novels, not just writing them. It is also why I am interested in Argead Macedonia - the kingdom up to Alexander. In fact, aside from work on Hephaistion, my real research interest is Archaic-era Macedon. I am thrilled by all the archaeological material coming out of Methoni and Aiani, Archontiko, and Vergina.

For those interested, the website for Dancing with the Lion, Welcome to Alexander's Macedonia has reader guides, including a glossary Riptide did not include, audio clips to hear how those so-odd-to-English-speakers Greek names sound, vlogs of areas in Macedonia mentioned in the novels, and also cut and extra scenes that did not make it into the novels, or that take place in the year between the two.

DC: What was the process to develop Hephaestion's character given that the historical record is rather limited to Alexander's historians?

JR: Hephaestion's character was built on my own professional research. My (long-ago) dissertation concerned him, I have published a number of articles about him, and now I am working on a monograph that is a much updated version of the dissertation.

I tell people that writing fiction makes me a better historian, which can elicit a scoff. But it does. In history, we must qualify. We build probabilities and possibilities from the primary evidence, then cite that evidence to support it and evaluate our sources' reliability (historiography). But there is another layer beyond educated hunches; stuff we strongly suspect but cannot prove. Fiction allows me to play with that. My friend and colleague Sabine Müller once described him as “barely a palpable person” (translating from German). She is right, but a novel cannot have a barely palpable main character, so I take the probable and possible, then wrap those bones with sinew and skin from my hunches and outright fictionalizations.

Ergo, I can tell a reader what parts of fictional Hephaestion are based on stated details (the friendship with Alexander/being educated together); what is conjecture based on evidence (his Athenian ancestry and mathematical ability); and what is pure imagination (that his father was a horse breeder and he had three older brothers who all died before the story begins). All those things blend to create a 3D character who is not just Alexander's shadow. Hephaestion is, arguably, the real chief protagonist of the novel.

DC: As someone who enjoys ancient languages, I loved seeing some Greek in texts like οἴμοι, ίδού, and χαῖρε.

JR: I am glad you liked the Greek! I think most readers liked or at least were okay with it, even if a few complained. One reviewer asked why did I have to use 'fibula' instead of 'safety pin'? Well, if I had used 'safety pin' how many readers would have cried, “Anachronism! They did not have safety pins!”, when they most certainly did. Using Greek terms heads off some of that at the pass. Oimoi presented a different problem. How do you translate that into English (“Woe am I!”) without sounding goofy or, again, anachronistic? I kept the Greek; people get used to it with repetition, and I think it adds ambiance.

DC: You placed Alexander under a new spotlight that shows his raw emotions and his development within Macedonian society. This depicts Alexander as being a product of Macedonian culture and his environment; would you be willing to elaborate on why this was the case?

JR: Ancient Macedonia was not the barbarian backwater Athenian orators such as Demosthenes painted. It had brilliant architecture, artwork, and a unique culture and religious expression, long before Philip II or Alexander. Some of the goldwork and sculpture from Archaic-era Aiani, Vergina, and Archontiko is astonishing. As I entered the study of Greece “from the north,” I wanted readers to hear Alexander's story “from the north.” Ancient Greece was not a uniform country; cultures varied from city-state to city-state, or in border regions such as Thessaly and Macedonia. Too often “Greek history” = “Athenian history” because we are prisoners of our evidence, and most of that is Athenian. Dancing with the Lion flips that.

I try to lean into Alexander's Macedonian culture in everything from religious expression to something as simple as wearing fancy patterned clothes in Athens and being made to feel pretentious for it. Macedonians did not want to be Athenian any more than Thebans did, or Argives, or Spartans. They were proud to be Macedonian. If we want to tell Alexander's story fairly, we must unlearn Athenian propaganda about Macedonia.

Since Manolis Andronikos opened the Royal Tombs at Vergina in 1977 CE, our understanding of Macedonia has grown in leaps and bounds. Yet this trickles out to a general audience slowly, not least because many archaeological reports are in modern Greek. Even specialist material in English typically appears first in article form in academic journals or edited collections not easy to access for the average person. Like me all those years ago, most non-specialists reach for a biography first.

At the end of my Author's Note, I include a brief list of research material I employed, notable names and useful collections, to guide interested parties through the quagmire of (English-language) material on Alexander. Some seminal scholars do not have books, or even that many articles (e.g., Charles Edson and Harry Dell, who along with Nick Hammond, essentially invented the field of Macedonian Studies). Thus, reliable historiography on Macedonia can be challenging without help.

DC: What plans do you have for the future? Do you plan to take on another fictional tale or do you plan to head back over to the non-fiction section and continue more research?

JR: Actually, I am doing both at once. As noted, I am currently researching a monograph about Hephaestion, and just finished a longish article with a digital history component that has taken me years to compile; hopefully, it will be accepted to a journal. Covid-19 has sidelined monograph research by requiring me (like many professors) to put next year's ('20/'21) classes online, but I hope to get back to the monograph next summer.

By contrast, writing fiction is my relief valve. While I do hope to return to Alexander eventually, I must allow for the realities of publishing. Historicals are a hard sell. Without going into detail, I am setting the series aside for the moment. That said, if you as readers like the novels and want more of Alexander, post reviews/ratings on Goodreads. That is what publishers look at for the viability of future sales.

Right now, I am working on an epic fantasy series called Master of Battles. It borrows from history, then mixes up the pieces and adds fantastic creatures - dragon-horses and jewel bats - and magic of course, but not of the Blue-Boltz variety. It is a magical system based on American indigenous thought. The plot concerns a psychopathic witch (wabeno) who plans to infiltrate and control a decaying world-power, the Shim Empire, which is not unlike the Roman Empire, but in the east. Imagine a smaller landmass and no Himalayas where Persia, India, and China united. Our two main protagonists come from very different worlds but must combine forces to take down the witch. Aside from the plot, the series deals with a lot of heavy themes including what it means to be civilized, and issues of gender. Readers familiar with ancient history should recognize a lot, but with different names and in the “wrong” place. That is all part of the fun.

Jeanne Reames teaches Greek, Macedonian, and Ancient Near Eastern history at the University of Nebraska-Omaha, where she also directs the Ancient Mediterranean Studies Program. You can find her full author bio on her website.

Keep up with her on:

Blogger (http://awomanscholar.blogspot.com/)

Tumblr (https://jeannereames.tumblr.com/)

Twitter (https://twitter.com/Jeanne_Reames)

Facebook (https://www.facebook.com/jeanne.reames.3)

Instagram (https://www.instagram.com/jeannereames/)