The treasure ship Madre de Deus (aka Madre de Dios) was a Portuguese vessel carrying hugely valuable cargo from the East Indies which was attacked and captured by a fleet of English privateers in the Azores in September 1592 CE. The ship, packed full of jewels, pearls, gold, silver, ebony, and spices, was the richest prize ever taken by the privateers who plundered the Atlantic during the long reign of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE). The capture was masterminded by Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE), and the £80,000 return on Elizabeth's £3,000 original investment helped repair relations between the adventurer and his queen, securing his release from the Tower of London. The fabulous treasure inspired many more privateering fleets to prowl the seas but none would ever make a capture as rich as the Madre de Deus.

Walter Raleigh

Although once a firm favourite of Queen Elizabeth, Walter Raleigh had fallen out with his monarch when she discovered the courtier and adventurer had secretly married one of her ladies-in-waiting, Elizabeth 'Bess' Throckmorton (1565-1647 CE). Raleigh was imprisoned in the Tower of London for his impudence in August 1592 CE. Fortunately, Raleigh had already organised a fleet to capture treasure ships of Philip II of Spain (r. 1556-1598 CE), and the unimaginable success it gained would be his ticket to freedom.

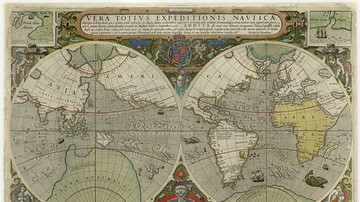

In the Elizabethan age privateers were sailors and adventurers who scoured the Caribbean and Atlantic for treasure ships carrying valuable cargo from the New World and Asia to Europe. Elizabeth often invested personally in these expeditions, and the spoils were shared according to the amount she and other investors had made in the project. Consequently, both the privateers and the state coffers were enriched by a practice which correspondingly depleted the wealth of England's great enemy: Philip II of Spain.

Raleigh had intended to command his latest privateer fleet personally but he was recalled to London the day after he set sail on 6 May 1592 CE. The queen had discovered his secret marriage and Raleigh was replaced as commander of the fleet by Martin Frobisher (c. 1535-1594 CE). Raleigh dithered but after two weeks he did return to London and captivity.

Backed by investors which included the queen, George Clifford, the Earl of Cumberland, a consortium of merchants and Raleigh himself, the fleet was well-equipped. The original plan was to sail for the Isthmus of Panama and attack the annual treasure fleet which sailed from the Americas to Spain laden with gold, silver, and other loot. First, though, they sailed to Spain and then divided, Frobisher taking some ships to Cape St. Vincent in southern Portugal while the remainder headed for the Azores in the mid-Atlantic. This latter group was commanded by Sir John Burgh and was reinforced by the arrival of six more ships sent by the Earl of Cumberland. Burgh arrived in the Azores on 21 June where, to his chagrin, he discovered he had already missed the first ships due in from the East Indies.

The Attack

The Azores fleet first came across the carrack Santa Cruz. A Portuguese vessel (that country then being ruled by Philip of Spain), it had been blown onto the shore of one of the islands by a storm. The Portuguese crew were busy unloading what they could salvage from the ship and they then set fire to the vessel. Burgh landed on the island with a small force and took over the beached cargo which was not of tremendous value. Under coercion, one of the captives revealed that three more carracks were behind schedule from their departure port of Cochin on the East coast of India (now Kochi) and had yet to make the Azores. As it happened, two of these ships had already been wrecked in storms. The English had just one chance for glory. Burgh stationed his fleet near the coast of the island of Flores and waited. The line of ships were rewarded with the sight of a sail on the horizon on 3 August.

If the Santa Cruz had been disappointing, the Madre de Deus, on the other hand, was a whole different story. With a crew of 700 men and hull bristling with 32 cannons, this 1450-ton giant would be no easy capture, though. None of the English ships could anywhere match the Madre de Deus' keel length of 30.5 metres (100 ft.) or beam of 14 metres (31 ft.). First built in the 15th century CE, the carrack type was designed for stability in heavy seas and offered a very large space for cargo making it anything but nimble in handling. Slow to turn, this class of ship was especially vulnerable from the bow while most of its firepower was from the stern. If the English ships could co-ordinate their attack and steer clear of the Portuguese cannons, the battle would have only one outcome.

The fleet of English vessels (the exact number of ships is not known but there were at least seven) attacked at intervals in what became known as the Battle of Flores. The Portuguese vessel's crew fought bravely, the battle dragging on into the night, but eventually, they were overpowered by sheer numbers. At one point it seemed likely the Madre de Deus would run aground, damaging its cargo, and so two English ships were deliberately crashed into it to keep the Portuguese vessel safely at sea. When the stricken ship was finally boarded the English mariners could not believe the spectacular riches they found in the cavernous hold.

The Ship's Manifest

The Madre de Deus was filled with over 500 tons of cargo, a veritable Aladdin's Cave of all the treasures of the East. There were the obvious diamonds, rubies, pearls, and gold and silver coins. There were, too, bales of fine cloth and rolls of silk, exotic animal hides, luxuriant carpets, wall-hanging and quilts. There were chests full of crystalware, Chinese porcelain, jewel-encrusted tableware, and finely-crafted jewellery of all types. Larger goods included pieces of valuable unworked ivory and ebony. There was, too, a rich cargo of pepper, rare perfumes (frankincense, musk, benjamin, ambergris, and camphor), cochineal dye, exotic spices (cloves, ginger, and nutmeg) and precious medicinal herbs.

Dividing the Spoils

The single richest prize ever taken by Elizabeth's privateers, captained now by Christopher Newport, was sailed triumphantly into Dartmouth harbour on 9 September. At the Azores, the captains and sailors had already plundered at will. The mariners were so mad-keen to delve into the ship's treasures their candles had set the hold on fire in five separate incidents. Significantly, the Madre de Deus was 1.5 metres (5 ft) higher above the waterline when it made England than it had been when it left the East Indies.

There was still much pilfering going on by English parties even as it docked. So, too, there were squabbles amongst the multiple investors of the whole enterprise over who should get what. Sir John Hawkins, then head of the Royal Navy, advised the queen that Raleigh was the best man to sort out this mess of spoils, retrieve what he could from the light-fingered sailors, and salvage what remained for sale to merchants. Accordingly, Raleigh was released from the Tower on 15 September and sent to Dartmouth with a keeper to ensure he did not make a run for it.

When Raleigh arrived at the docks he found that much treasure had already been looted by the sailors who were now doing a brisk trade with local merchants and jewellers. A commissioner sent to officially assess the value of the treasure ship, Robert Cecil, reported that he could smell cloves, pepper and musk 11 kilometres (7 miles) from the docks as mules were brought in to spirit away the ship's cargo before the authorities could step in.

It proved impossible to retrieve the small valuables that sailors had long-since pilfered, broken down and sold, and Raleigh was reluctant to pressure the crews who had, after all, only been claiming their share of the enterprise's profits. Raleigh did manage to sell off the more cumbersome goods still left in the ship's hold and so Elizabeth got more than her fair share, perhaps around £80,000 worth on her original investment of £3,000. The remaining goods were valued at over £60,000 and divided amongst the investors. The value of those goods already looted before being properly inventoried was perhaps a further £650,000. Despite this glittering gift horse, Raleigh was given his freedom but not quite forgiven for his past indiscretions and so was forbidden to see the queen for another year. Elizabeth Throckmorton, meanwhile, was never forgiven and obliged to live a retired life at Raleigh's home in Sherborne, Dorset.

The capture of the Madre de Deus inspired the continuation of Elizabeth's privateers but, in reality, the policy was never carried out in a systematic and coordinated manner and the returns were ultimately disappointing for the huge costs of manning ships to roam the high seas. The Madre de Deus was a marvellous and glittering highpoint in privateering that would never be matched.