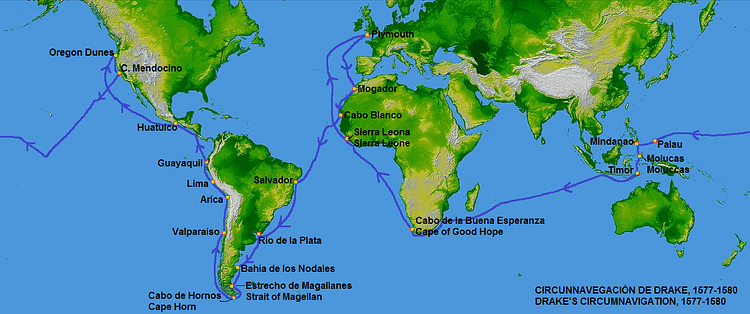

The English mariner, privateer, and explorer Francis Drake (c. 1540-1596 CE) made his circumnavigation of the world between 1577 and 1580 CE. Only the second to achieve this feat after the expedition of the Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan (c. 1480-1521 CE) did so in 1522 CE, Drake did not attempt any speed record and spent months along certain coastlines prowling for opportunities to add to the ever-growing hoard of loot down in the hold of his ship the Golden Hind. The extraordinary voyage included battles in Spanish colonial settlements, the capture of treasure ships, and a near-mutiny as well as the usual maritime hazards of storms, scurvy, and running aground on coral reefs.

Exploring the Unknown

The idea to mount an expedition to explore what lay south of the equator and see if a great southern continent - 'Terra Australis' - did really exist was first touted by Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE) in 1574 CE. Grenville had failed to find backing for his plan as the search for the Northwest Passage took precedence, but in 1577 CE, Elizabeth turned to Drake for just such a southern voyage. Secretly, the queen invested in the project and instructed Drake not only to explore new trade possibilities but also to take whatever treasure he came across from the Spanish and attack Spanish colonial settlements in South America. For this task, Drake was given command of a fleet of five ships:

- Benedict (15 tons, but later swapped for a 50-ton Spanish ship captured off Africa and renamed Christopher)

- Elizabeth (80 tons)

- Marigold (30 tons)

- Pelican (150 tons)

- Swan (50 tons).

Mid-voyage the Pelican, Drake's flagship, would be renamed the Golden Hind in honour of the expedition's principal patron, Sir Christopher Hatton, who had that device on his family coat of arms. The voyage was organised as a joint-stock company where multiple backers agreed to accept any liability in the hope of receiving future profits proportional to the amount they had originally invested. Drake's backers would not be disappointed.

The Atlantic & Mutiny

In November 1577 CE Drake set off with 164 men on what would turn out to be an extraordinary voyage; 60 of the men would never see England again. The expedition got off to the worst possible start when a storm damaged several of the ships and they were obliged to return to port only two weeks after setting off. The fleet set off for a second time on 13 December and sailed down the coast of northwest Africa and then across the Atlantic route via the Cape Verde Islands. Three ships were attacked and their cargoes looted; one of them, the Mary, was added to Drake's small fleet.

The ships passed through the Doldrums and crossed the equator. There was some trouble with a Thomas Doughty who had been made captain of the Mary but who then gave a speech questioning Drake's plans and right to command. Drake had Doughty put in the brig of the Swan. After two months with no sight of land, the fleet finally reached the eastern coast of South America, north of the River Plate, in April 1578 CE. After a bad storm, Doughty was again stirring up mutiny and Drake struggled to keep the ships together as one fleet. The Christopher, Swan, and Mary would all be abandoned by August as too unseaworthy to make the voyage into the Pacific Ocean.

Landing in Patagonia, a trial was organised for Doughty who still insisted he was the true leader of the expedition. The spot was exactly where Magellan on his circumnavigation expedition had hanged a mutinous captain half a century before - the ruins of those gallows were still, ominously for Doughty, in plain view. The jury of 40 men found the mutineer guilty and gave him three options: to be executed, marooned where they were or sent in chains back to England. Doughty chose the first (or the jury did, depending on the version of the story) and he was beheaded on 2 July 1578 CE. At this crucial moment in the voyage, Drake called all his men ashore again and assured them he was absolutely in command. To reinforce this Drake dismissed all of his officers, who had been appointed by the expedition's backers, and reappointed his own choices. The same men were appointed officers again but the point was clear: Drake was in command not the investors back in England. Further, all men would now perform the same duties, regardless of rank. Drake had managed to pull his men together and get the expedition back on its right course.

At the southern tip of South America, the three remaining ships pressed on through the Straits of Magellan in August. The Straits were difficult to find and dangerous, but after getting through, heavy storms in September meant that the Marigold was wrecked and the Elizabeth sailed back to England. The Pelican was obliged to continue the expedition alone. It was when he reached calmer Pacific waters that Drake renamed the Pelican the Golden Hind. Doughty had been Hatton's man and so it may be that the renaming of the ship was an attempt by Drake to signal continued good faith with his sponsor.

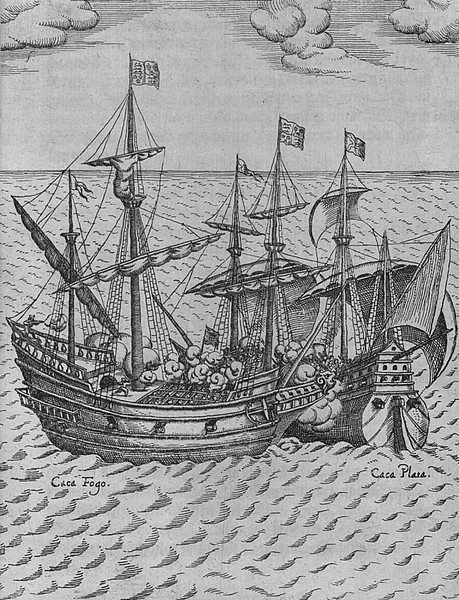

The Golden Hind

No precise drawings of the Golden Hind galleon survive and its design - realised in scale models and one full-size replica - has been surmised from descriptions. It was small even for Elizabethan ships, weighing in at 150 tons (for comparison, Bligh's HMS Bounty was 215 tons and Cook's HMS Endeavour was 370 tons). Around 30.5 metres (100 ft.) in length and with a 5.5-metre (18 ft.) beam, the draught when fully loaded was almost 4 metres (13 ft.). It had a forecastle, after-castle, and three masts with a total sail area of 4,150 square feet. Each side of the ship could present seven cannons which could be withdrawn behind their hatches. The poop deck had two further cannons while a number of smaller cannons could be used where most required. It carried two disassembled pinnaces for close-to-shore work. Drake frequently used expert pilots when in unfamiliar coastal waters and the experienced Portuguese pilot Nuño da Silva (captured with the Mary) described the Golden Hind as:

…very stout and very strong, with double sheathings…She is a French [style] ship well-fitted with good masts, tackle and good sails, and is a good sailor, answering the helm well. She is neither new, nor is her bottom covered with lead…She is staunch when sailing with the wind astern if it is not very strong, but in a sea which makes her labour she makes no little water.

(Williams, 119)

The Golden Hind had a crew of 90 men. Only the nine officers had a cabin and most of the crew slept on the gun deck. Drake ensured his ship was well-fitted for relative comfort and had good furniture. This was especially so for his own cabin which was lined with oak and boasted a bunk, desk, chair, and chart table where the explorer tracked his course and made sketches and paintings of the sights and coastlines he came across. Drake also had a small library which included a record of Magellan's circumnavigation expedition. Surviving today from this cabin is the captain's sea chest, a large rectangular box covered in leather and with ships painted on the inside of the lid. Another survivor is Drake's drum which is said to roll mysteriously whenever England is in danger.

South America

Drake sailed the Golden Hind up the west coast of South America. In November, on the island of Mocha off the coast of Chile, a group of indigenous peoples attacked a number of the mariners when ashore. Drake was hit near the eye by an arrow and made a lucky escape. Spanish settlements like Valparaiso were then taken completely by surprise in December 1578 CE when an English warship showed up in Pacific waters. Drake made off with 25,000 gold pesos from the raid (the Spanish claimed losses of 200,000 pesos). Several poorly armed treasure ships were subsequently captured in the harbour of Callao, the port of Lima. The Golden Hind recrossed the equator on 28 February 1579 CE.

Next, on 1 March 1579 CE, he took the greatest prize of the entire voyage, the Nuestra Senora de la Concepćion (aka Cacafuego) off the coast of Peru with its massive cargo of silver intended for Panama. Drake had captured this floating Aladdin's Cave by making the Golden Hind appear a slow ship. This was done by having all sails billowing but also towing heavy chains; when the latter were cut free under the cover of darkness, the ship bounded over the waves to stun the mostly unarmed Spanish into submission. It took six days to relieve the Spanish of their riches and these weighed so much that Drake was obliged to jettison some of the Golden Hind's ballast to make room. There were an astonishing 13 chests of plate, 36 kilos (80 lbs) of gold, a mass of gemstones, and 26 tons of unworked silver.

More captures followed off the coast of Nicaragua, Guatemala, and Mexico, Drake often putting the crews ashore and adding rolls of fine silk and cases of Chinese porcelain to his already bulging hold. Another very useful acquisition was Spanish charts indicating the routes galleons took to cross the Pacific and reach Manila.

Indonesia

Drake, provisioning his ship well for the months ahead, was then swept across the Pacific by the trade winds. In October he reached the East Indies (Indonesia and Philippines) and took on board spices, ginger, pepper and six tons of valuable cloves from the Moluccas (aka Spice Islands) where, luckily enough for the English captain, the sultan was at war with the Portuguese. Extensive repairs were made to the ship north of Java, and in early 1580 CE, they navigated through the treacherous islands and reefs of Indonesia. The ship grounded on a reef in January which necessitated Drake jettisoning the six tons of cloves and a number of cannons to lighten the ship. It was touch and go if the ship would make it, but a heightening tide and strong wind lifted the Golden Hind to safety. Francis Fletcher, the ship's chaplain, who would later write an account of the voyage (The World Encompassed, published in 1628 CE), had told the crew the beaching was God's punishment for Drake's treatment of the mutineer Doughty. Drake would brook no such dissent of his command and so excommunicated the chaplain in his capacity as captain and made Fletcher wear a sign around his neck stating: 'Francis Fletcher, the falsest knave that liveth'. The chaplain was forgiven and reinstated in his duties a few days later.

Homeward Bound

In March 1580 CE the Golden Hind crossed the Indian Ocean. In June, Drake rounded the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa where rainstorms were gratefully received to refill the ship's empty freshwater caskets. Drake sailed up the Atlantic coast of that continent to reach Sierra Leone in July, again desperately short of freshwater. Towards the end of August, the sailors reached the Canary Islands and then made port at La Rochelle in western France. Back on the familiar home stretch, Drake arrived at Plymouth on 26 September 1580 CE. The voyagers had been around the world, albeit not in a direct or even hurried manner, for two years and nine and a half months.

Much more important at the time than the geographical achievement was the treasure Drake had been relentlessly filling his ship with along the way. The estimated value of the loot was perhaps £600,000 (more than double the entire annual revenue of England), and the queen personally received a handsome £160,000. An inventory of the treasure brought back, signed by Drake on 5 November 1580 CE, survives today in the archives of the Tower of London. On arrival, the queen invited Drake to an audience at Richmond Palace and told him to bring some choice samples of his fabulous treasure.

On 4 April 1581 CE, Elizabeth boarded the Golden Hind docked at Deptford on the Thames and, pleased with the treasures he had captured and the glory of his navigational achievements, knighted Drake on its decks. This outraged the Spanish ambassador who regarded Drake as nothing more than a pirate. However, if the queen knighted Drake and took from him a part of his gains - and queens do not deal in stolen goods - then he could not have been acting as a pirate but as a representative of his monarch. The message to Spain was clear: allow legitimate trade in the New World or face the privateers.

Drake had become Elizabeth's favourite sea dog, a feeling that must have been mutual as the mariner gave his queen lavish gifts such as a gold crown embedded with five huge emeralds and a diamond-studded cross. The queen gave gifts in return, notably the silver cup in the form of a globe which encased a coconut Drake had brought back from his voyage. Another present was the now-famous Armada Jewel by Nicholas Hilliard in 1588 CE, a gold and gem-encrusted brooch carrying two portraits of the queen. Drake, in terms of cash in his pocket, was probably then the richest man in England and he splashed out on a portfolio of properties which included Buckland Abbey. He acquired, too, a coat of arms (a ship atop a globe with two silver stars intersected by a wavy horizontal line or fess). His official motto became Sic Parvis Magna or 'Greatness from Small Beginnings'.