Besides the traditional option of private tuition, Elizabethan England (1558-1603 CE) offered formal education to those able to pay the necessary fees at preparatory schools, grammar schools, and universities. There was, however, no compulsory national system of education, no fixed curriculum, and still only a small number of children were sent to schools, but it was a progression from the situation in the Middle Ages. The idea prevailed that education was a luxury and designed to prepare children for the working life they would assume when adults. Study solely as a pursuit of knowledge was still largely limited to the clergy or the idle rich. Far fewer girls received an education compared to boys, and the universities were entirely male-dominated but at least now offered courses in subjects other than religious matters. Consequently, although opportunities had widened, the level of one's education still depended on gender and class. Still, over the latter half of the 16th century CE more people were being educated than ever before and levels of literacy greatly improved thanks to some free schools, the presence of relatively cheap grammar schools in most towns, and the increased availability of printed reading matter and teaching tools.

Informal Education

When children reached around the age of six years old, they were taught by their parents and expected to contribute more to the daily life of the family. What they learned depended on their parents' own position. Children of farmers and artisans began to learn the skills needed for those kinds of work. Those with parents in the trades might enter an apprenticeship. The children in better-off families, the gentry and aristocracy, would have received private tuition and may also have spent time learning how to properly conduct themselves by living in the residence of a local noble (although this was becoming less fashionable) or even going abroad on the Grand Tour. The very rich would not have attended the schools mentioned below but the universities and Inns of Court did attract such students. Non-aristocratic children might also have received some private tuition to fill gaps and learn subjects their school did not provide such as French, dancing, or music.

Schooling was still mostly for boys as girls were not considered in need of it, given that they were expected to live a domestic life when adults. Girls were only taught to read so as to appreciate the Bible, but some did receive a better education beyond the preparatory schools, thanks to enlightened parents, or if they were children of the aristocracy, via private tuition. Schools specifically for girls would not arrive until the 17th century CE. There were some institutions in the Elizabethan era that took in girls only, but these were akin to babysitting services where the adult guardian was often illiterate themselves.

Preparatory Schools

There were a number of small preparatory schools (aka ABC, alphabet or 'petty' schools) for young children, and these offered a rudimentary education, focussing on the alphabet, communal reading, and simple arithmetic (writing was not seen as absolutely necessary at this stage). Reading was done first and only if satisfactory progress was made did a pupil move on to mathematics. The result of this policy was that many children never learnt how to do anything else but count. Writing could be learnt separately from school by paying a scrivener (a professional copyist who specialised in creating legal documents), but it was not easy in a time without dictionaries and when there were varied forms of spelling and punctuation based only on custom. Another complication was the letters i and j were considered the same (j often being used as the capital), as were u and v (the latter often being used only at the beginning of words).

The English Reformation ensured the separation of the Church from education but children still learnt prayers and the catechism, and religious texts were often used to teach reading. The children of more religious parents, especially Puritans, were obliged to regularly read and memorise parts of the Bible. Perhaps around 30% of men and 10% of women were able to read and write in late-Elizabethan England although figures varied wildly in regard to urban and rural populations, class, wealth, and amongst certain trades. Literacy in London may have been as high as 80% as many people were attracted to the city for the very reason of the educational opportunities on offer in the capital.

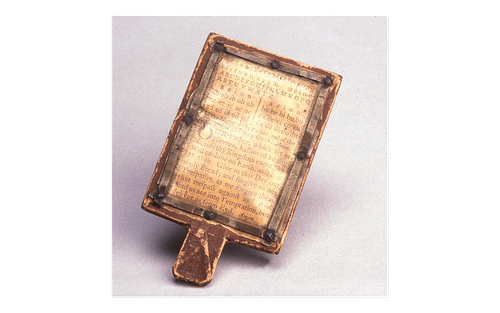

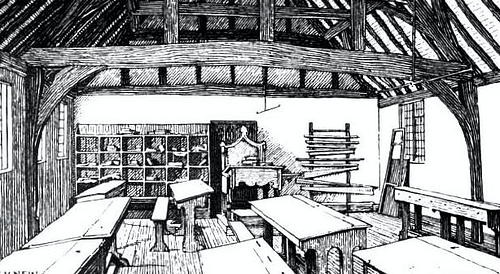

The teachers at preparatory schools varied tremendously in terms of their own skills and knowledge, only around one-third would have studied at a university themselves. Teachers had few materials to help them in their work - perhaps a board, a counting frame, and picture cards they made themselves - but one ubiquitous item was the horn-book. Shaped like a paddle, a written text was pasted onto a wooden board and covered by a protective layer of horn. These horn-books were especially used to teach children the alphabet or provide a short and simple reading text to work with. Another tool, although one of more dubious didactic value was a birch rod, used extensively to punish children. Despite the threat of a thrashing, discipline must have been difficult to maintain as the classes were often large with five or six multi-levelled and multi-aged groups within them. Children at the same level sat on a single bench or form - which is why in English schools today some class groups such as those to take the morning register attendance are still called 'forms'. In the Elizabethan period, the age of the child did not often relate to what they studied, much depended on individual ability rather than the modern idea of moving a whole class of the same age along a fixed curriculum. Children sitting on the same form, then, could be of various ages.

Preparatory schools could be managed by a local town council, a parish or a trade guild. Like grammar schools, they might have been established by a rich benefactor (endowed schools) or were maintained by a community subscription. Some preparatory schools were free - although there was a small fee for materials, candles, fuel, etc. - but most preparatory schools charged a fixed quarterly price. Some of these establishments were private, and they might, too, be affiliated to a grammar school, which just about every major market town now possessed. Alternatively, some youngsters may have progressed to a cheap private tutor, a role often taken on by women and some members of the clergy.

Grammar Schools

A boy who performed well at a preparatory school and whose parents had the necessary means could be sent to a private grammar school. Some girls might be sent but typically did not attend after the age of nine or ten. Most pupils attended from around the age of seven to nine and the curriculum was based around the classics, especially the learning of Latin and, much more rarely, Greek and even Hebrew. The Bible was a popular text, along with works of Greek and Roman literature with a bit of modernity thrown in such as the works of Erasmus (1466-1536 CE).

Classes began early, around 6 in the morning and finished for lunch at 11 am. The afternoon lessons began at 1 pm, and the day finished at 4 or 5 pm. The day was shortened by an hour at either end in the winter months, and pupils were usually left free on Thursday and Saturday afternoons. Classes were led by a teacher or 'master' who was assisted by an usher (who also went by the splendid name of hypodidascalus). Sometimes older boys would teach the younger ones for them to polish up their Latin and reach the required standard needed in the lessons with the master.

Memorising texts and performing endlessly tedious translations of Latin phrases was the norm, even if some scholars like Erasmus questioned the value of these methods. Creating situations of competition between pupils with an atmosphere of fear of physical punishment and humiliation was the usual approach. Although there were rewards such as a place in a higher class, or for group teaching, which was common, an entire class could be given a half-day holiday or permitted a period of 'misrule' to let off steam. Many masters would have employed more progressive ideas, but then, as now, one suspects that results were what mattered in the end for the school's owners and parents and that to be seen to be learning was more important than actually learning. In short, education was established to teach the subject and not the child.

Schools often had a mix of boarders (aka 'tablers' because they stayed for lunch and dinner) and day-only pupils, charging a small fee and often differentiating between pupils who came from the town or outside it. Fees were a few pennies per day but could add up to some £20 per year and so were beyond the means of some tradesmen. The school year was a tough one with the only holidays being a couple of weeks at Easter and Christmas. Pupils who lasted the course might leave the grammar school at the age of 14 or 15, although some continued until they were 18.

Grammar school teachers were as keen on discipline as in the preparatory schools so the birch cane (or a bundle of them) would have been painfully remembered by most pupils. Although the majority of the teaching was done orally, there were some printed textbooks for Latin grammar and vocabulary, and for arithmetic. Relief from the rather tedious curriculum was provided by some time spent on sports. Non-academic activities included running, wrestling, archery, and chess. Finally, then just as now, some schools organised an annual play, which involved much rehearsal and preparation throughout the academic year.

The Universities

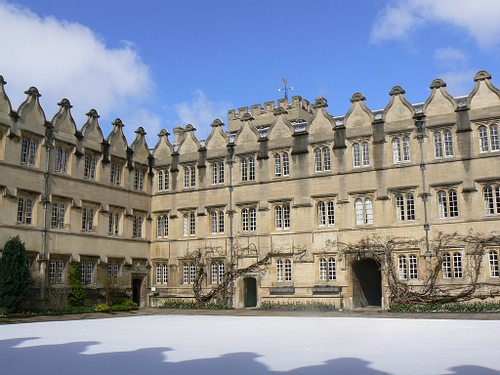

Oxford and Cambridge universities were founded in the 12th century CE and, concentrating on preparing boys for a career in the Church, they went from strength to strength as independent institutions where students, teachers, and scholars (fellows) lived and studied together in one place. By the 16th century CE the universities had lost their independence and were controlled by the Crown. The Reformation had largely wiped away their original purpose and so the universities struggled to attract students. During Elizabeth I of England's reign (1558-1603 CE), however, they made a comeback thanks to the gentry sending their sons for a higher and broader secular education. As, even at this level, education continued to be seen as something that helped one in one's future career as opposed to a pursuit of knowledge for its own sake, women were not present. Males who attended varied in age from 14 to 18 as, again, performance at preceding levels was the most important factor.

The universities were organised as individual colleges with teaching being carried out in small groups and one-to-one tuition. A basic degree course typically lasted four years (a Master's degree was up to seven years), and subjects focussed on the well-established seven liberal arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music). Additionally, the three philosophies (moral, natural, and metaphysical) were studied in detail. The ideas of Humanism which had become popular during the Renaissance greatly influenced the curriculum with the idea that, once armed with a knowledge of Latin and Greek, students could learn from classical texts the civic values which would allow them to best serve their careers and the state. Studies also evolved to reflect changing patterns in wider society, especially an interest in trade, history, and geography.

Finally, the universities never quite lost their old ties to the Church, and many clergymen took a higher degree in divinity; indeed, now that the monasteries had disappeared, ecclesiastical libraries were much more difficult to find. Even more humble clergy were now attending university as were pupils not from elite families. Such were the chances of mixing with different classes, sons of aristocrats were warned in printed guides of the dangers of mixing with anyone other than their peers.

By the end of the century, some 500-600 students were welcomed each year at Oxford and the same number at Cambridge University, although not all would complete their four years. At any one time, these two universities might have 1800 students each. Over the decades the pattern was set that anybody who became anybody in England attended Oxford or Cambridge. The majority of Elizabethan Members of Parliament, court officials, and Justices of the Peace were all alumni.

Inns of Court

Graduates of the universities or those who left mid-course often moved on to the Inns of Court, which were institutions offering the study of Common Law, or more specifically, an apprenticeship in that field. There were also the Inns of Chancery, which offered studies in Parliamentary Proceedings and a more basic introduction to legal matters. The name of these institutions derives from the fact that students of Common Law in the 14th century CE came to reside in particular inns. Four such inns in London were Gray's Inn, Lincoln's Inn, Middle Temple, and Inner Temple, and these collectively became known as the Inns of Court. On completion of their studies, the students were issued with a license to represent clients in the law courts, which were booming with an unprecedented wave of litigations.

Courses involved lectures, practical tests, moots (mock trials), and debates, all given or supervised by experienced practitioners. Passing the course meant being 'called to the bar' of the Inn and receiving one's license to practise, an expression which still prevails in England today for newly qualified lawyers. Curiously, by the Elizabethan period, the Inns of Court also attracted young men who had not the slightest intention of becoming lawyers. This is because the Inns came to be regarded as a suitable place for the gentry to round off their education, much like a finishing school, and, not of the least importance, it was a place where one could make many useful connections for one's future career. As always, one suspects that in the Elizabethan period it was always more important who one knew than what one knew.