The history of the ancient world has always been told as a history of cities, from Homer's epic poems about events just before and just after the sack of Troy, through the prose histories of wars between Athens and Sparta, Rome and Carthage. From the 5th century BCE, most historians, dramatists, philosophers, orators, and scholars spent much of their lives in cities, and crucially so did their readers. When Renaissance political theorists and painters discovered what has come to be known as the classical past, the city had centre place. In one way or another, that remains true today when we imagine antiquity through films and games, and when we visit historical monuments.

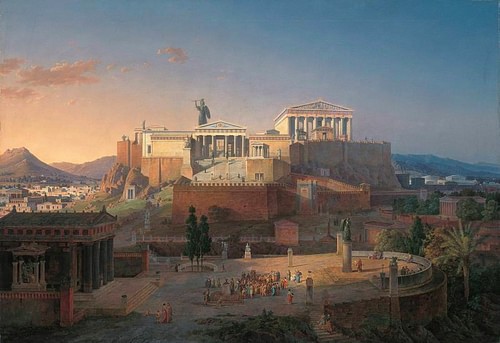

It has been a surprise, then, to realise how different their cities were from ours. For a start, they were small, even compared to similar cities in other parts of the ancient world like Egypt and the Near East. Only a small proportion of the population lived in cities. This varied from place to place, but sometimes less than 10 per cent of the population lived in cities. Their monuments inspired the imperial architectures of Washington and Paris, Vienna and Berlin. But it took imperial Athens a generation to build the temples on the Acropolis, and spectacular as they remain, they are tiny compared to those of 19th- and 20th-century CE capitals.

What I set out to do in my book The Life and Death of Ancient Cities was to explore some of these differences. Why did cities appear so late in the Mediterranean world? Why were most of them so small? What gave them their extraordinary resilience? (Most ancient cities are still inhabited today, and some have been continually inhabited for around 3,000 years.) I also wanted to understand the exceptions. How did just a few cities buck the trend and for a while welcome hundreds of thousands of people? And why did some cities die or shrink until they were no more than villages?

The answers in this book draw on recent archaeology and ancient history but are inspired by other disciplines including ecology, evolutionary theory, sociology, and biology. Unlike any other book about ancient cities, it does not revolve around a small number of famous cases, and very few individual humans are mentioned. Instead, it explores patterns of human settlement, the growth of networks, the fierce constraints imposed by the Mediterranean environment, the opportunities provided by new communications technology – sailing vessels, the domestication of donkeys, and road-building rather than air travel and the internet! I have tried to capture the astonishing diversity of ancient Mediterranean cultures but also tried to show how much they resembled each other when it came to the solutions they found to practical problems of urban life. I hope you enjoy this extract from it.

Hungry Cities

(Excerpt from The Life and Death of Ancient Cities)

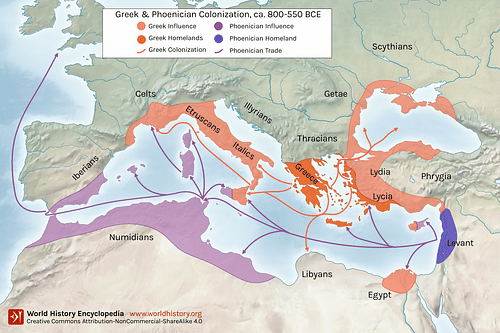

During the archaic period many of the first cities created around the Mediterranean had been built on a fine network of connections through which luxuries were exchanged for material of great value, metals in particular. Phoenician, Greek, and Etruscan traders played a key role in stitching the Mediterranean world back together. The origins of many Mediterranean cities lay in entrepôts established on favourable location on the networks established in this period. During the sixth and fifth centuries this changed, as a mass trade in commodities appeared on some of the same routes. The demand for some commodities also led some traders outside the Mediterranean, seeking grain from Egypt and south Russia and exploring areas like the Adriatic and southern France that gave access to the resources of temperate Europe. There is no doubt that the growth of states and the spread of cities within the Mediterranean was a powerful factor in making the trans-regional trade in mass commodities profitable. Bigger cities were the hungriest. Athens sought suppliers of bread wheat from the Black Sea and the Nile Valley. But nonurban societies could generate demand too. Wine began to be produced in bulk and exported especially to the west. The increasing use of coinage from the sixth century meant there was increased demand for silver, gold, copper, and tin even after iron replaced bronze in many used. New technologies in water management made lead more valuable. The use of olive oil for food, for light, and for bathing increased. Timber, stone, and eventually livestock would join the list of commodities traded long distances. So would humans.

Shipbuilding and the construction of larger and larger temples created a demand for timber. There are few forests of tall trees in the central and southern Mediterranean, but fir and pine could be found in Macedonia and from the southern coasts of the Black Sea. Western Mediterranean cities turned to Corsica and to the wooded slopes behind Genoa. Classical urbanism did not result in widespread deforestation in all regions, but long timber became increasingly rare. Urban appetites extended beyond food and raw materials. Slaves were imported from southern Russia, from central Europe via the Adriatic, and from Western Europe via the Rhône Valley. Mercenaries too found their way from these regions into the central Mediterranean.

A new generations of trading cities grew on the back of this trade. Marseilles and its daughter cities in southern France did not just connect the Mediterranean Gauls with the urban network; they also provided a connection to routes up the Rhône valley. Greek ceramic has been found as far north as Burgundy and also in the Berry region. Classical writers credit the Massiliots with introducing viticulture and in general civilizing the Gauls. From around 500 BCE the cities of Adria and Spina at the head of the Adriatic provided Etruscans and Greeks with access to the Po Valley and also to central Europe east of the Alps. A series of small cities up the east coast of the Adriatic connected the Illyrians of the northwest Balkans with the wider Mediterranean world. Apollonia, also founded in the sixth century, was the most famous of these. In the north Aegean Torone, on the peninsula of Chalcidice, was a major shipper of timber. The area became a strategic priority in the fifth century when Sparta tried to limit Athenian access to the resources it needed to renew its navy. A string of Greek cities from Amphipolis in the west to Byzantium in the east provided access to the many Thracian tribes. Slaves, timber, soldiers, and metals passed back and forth through them. Beyond Byzantium the Sea of Marmara opened up into the Black Sea. The most important trading cities here were on the Crimean peninsula and along the south coast. The most successful trading cities of this period had deep harbours, suitable for the larger vessels needed for this kind of trade in bulk. Politically they mediated between powerful chieftains and various Greek alliances, mostly trying but often failing to avoid being controlled by either.

Economic and demographic growth in Europe, coupled with urban and political growth in the Mediterranean world, provided the perfect conditions for closer connections between the two regions. Northerners desired some southern manufactures, while Mediterranean peoples wanted the raw materials and slaves available from the north. The relationship was not always a stable one. Perhaps, as happened in other places and times, increased contact only made mobile populations more aware of what else was available in the Mediterranean world. The consequences were unpredictable. Barbarian invasions were certainly disruptive, but powers that resisted them – like Rome in the west or Pergamum in the east – might use the prestige they won to assert their hegemony. Dying Gauls in statuary proclaimed the success of Pergamon in keeping the Anatolian Galatians under control. The triumph of 187 BCE that followed their defeat by the Roman general Manlius Vulso was remembered as especially spectacular. As late as the last century BCE the Roman Senate reserved the right to declare a tumultus Gallicus as a kind of state of emergency. Well before that point, however, economic growth on the edge of the Aegean world had shifted the balance of power fundamentally. A tribal kingdom in the northeast Balkans had realized its economic potential and as a result moved from the margins to the centre of Greek politics. Its name was Macedon.

The kingdom of Macedon was the first great political force to emerge from the European interior. Philip II led armies south to become master of Greece, and his son Alexander the Great marched east to conquer the Persian Empire. Centuries of trade between Mediterranean cities and their continental hinterlands had awakened the potential of Europe, and Europeans were aware too of what riches lay to their south. Cities would continue for centuries to be the engines of economic growth around the Mediterranean. But from this point on they would be politically dominated by kings and emperors, and right up to the end of antiquity (and beyond) Mediterranean peoples would look anxiously north, wondering what forces were mustering in the woods and pastures of temperate Europe and on the Steppes beyond them.