Love, sex, and marriage in ancient Rome were defined by the patriarchy. The head of the household was the father (the pater familias) who had complete control over the lives of his wife, children, and slaves. This paradigm was justified, in part, by one of the stories related to the foundational myth of Rome in which the demigods Romulus and Remus argue, Romulus kills Remus, and Romulus founds the city of Rome in 753 BCE.

Shortly after this event (or just before), the Romans attacked neighboring tribes, taking their women, recounted as the famous Rape of the Sabine Women. These tribes then mounted a counterattack to win their women back but one of those taken – Hersila, who had become Romulus' wife – defended the Roman action in order to prevent needless deaths and encouraged the other women to do likewise. Whether the story reflects an actual historical event, it presents the paradigm of male-female relationships in ancient Rome: men held the power and women had to recognize that and respond accordingly. The social structure, informed by religion and tradition, dictated that men made the rules and women had to follow them.

This was the paradigm of love, sex, and marriage in ancient Rome and, although there were certainly exceptions, the evidence strongly suggests that the experience of most married couples adhered to this model. Romantic love, although recognized and praised by the poets, played little part in many marriages although there is evidence of strong marriages based on mutual love and respect. Sex, as an expression of passionate love, is frequently associated with extramarital affairs but must have also been an important component of many marriages. Marriage was considered the foundation of society, in many cases – among the upper class – a kind of business transaction in which the purpose of sex was to produce children, and romantic love in a marriage was a kind of luxury some would enjoy but many others, apparently, would have to do without.

Love in Ancient Rome

Although romantic love between husbands and wives is attested to in letters, inscriptions, and epitaphs, a great deal of what is known of love in ancient Rome comes from the poets in praise of women or boys they were involved with sexually, usually an extramarital affair on the part of one or both. The most famous poet in this regard is Catullus (l. c. 85 - c. 54 BCE) whose surviving work includes 25 poems addressed to his lover Lesbia, the pseudonym of a woman named Clodia, wife of the statesman Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer (l. c. 100-59 BCE).

Metellus Celer and Clodia were unhappily married and fought in public frequently, showing no sign of the passion she experienced with her lover. Catullus' poems to Lesbia express the highest adoration and the hope that she will leave her husband and live with him forever. In Poem 5 he writes:

Lesbia, come, let us live and love and be

Deaf to the vile jabber of the ugly old fools;

The sun may come up each day but when our

Star is out, our night, it shall last forever.

Give me a thousand kisses and another hundred,

Another thousand and, again, a hundred more;

As we kiss these passionate thousands, let us

Lose track; in our oblivion, we will avoid

The watchful eyes of stupid, evil peasants

Hungry to figure out

How many kisses we have kissed.

Catullus' hopes were in vain, however, as Clodia would not have been able to divorce her husband for another man. Divorce was an acceptable social option and could be initiated by either party but the grounds for divorce had to meet societal norms such as infertility on the part of the wife or abuse and neglect on the part of the husband. Adultery could be grounds for divorce but could not be brought by a wife engaged in an extramarital affair. After Augustus Caesar (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) came to power, he enacted laws concerning adultery which would have allowed Metellus Celer to kill both Clodia and her lover.

Other male poets, such as Ovid (l. 43 BCE - 17 CE) express similar feelings for their lovers who are either married or in some way unattainable. Some of the only poems regarding romantic love which differ from this paradigm come from the single female Roman poet whose work has survived: Sulpicia, daughter of the author and jurist Servius Sulpicius Rufus (c. 106-43 BCE). Sulpicia addresses her love poems to her boyfriend, a youth she calls Cerinthus, almost certainly a pseudonym since she states her family did not approve of him. Even so, she lives in hope that she and Cerinthus will be together one day. In Poem 1 she expresses her feelings about the beginning of their relationship:

I have finally fallen in love.

This is the kind of love that, if kept hidden, will benefit my reputation more

But revealing it to someone else is likely to damage it.

I prayed to Venus with my poetic talent and she brought it

And dropped it in my bosom.

Venus fulfilled her side of the bargain;

Now let me tell my story so that everyone can know.

I did not want to put any of it down in sealed documents just for my beloved to read.

It is nice to go against the grain

As it is tiresome for a woman to constantly force her appearance to fit her reputation.

I only want to be thought worthy of my worthy love. (Harvey, 77)

Unfortunately, as her later poems make clear, the relationship did not last because Cerinthus was unfaithful to her. She chastises him for making her feel like a fool when he clearly is “more concerned for that low-class whore in her slutty outfit than for Sulpicia, the daughter of Servius!” (Poem 4, Harvey 77). What happened to Sulpicia afterwards is unknown but, in keeping with the paradigm of Roman patriarchy, she probably was given in marriage to some other youth her father approved of. Scholar Brian K. Harvey comments on women's status in ancient Rome and how their lives were defined in relation to males:

Unlike men's virtues, women were praised for their home and married life. Their virtues included sexual fidelity (castitas), a sense of decency (pudicitia), love for her husband (caritas), marital concord (concordia), devotion to family (pietas), fertility (fecunditas), beauty (pulchritude), cheerfulness (hilaritas), and happiness (laetitia)…As exemplified by the power of the paterfamilias, Rome was a patriarchal society. (59)

Husbands, or males in general, were not held to these same standards of virtue and this was as true of sex as of any other aspect of male-female relationships.

Sex in Ancient Rome

These relationships were defined by the pairings of twelve gods collectively known as Dii Consentes (also given as Dei Consentes) who modeled appropriate sexual and marital behavior for human beings. These six divine couples were:

- Jupiter and Juno

- Neptune and Minerva

- Mars and Venus

- Apollo and Diana

- Vulcan and Vesta

- Mercury and Ceres

The religion was state-sponsored – the state honored the gods and the gods blessed the state – and so adherence to the models of the gods was considered vital to the health and prosperity of Rome. The best-known example of this is the Vestal Virgins, women who served the goddess Vesta and remained chaste for the entire tenure of that service. The model of the Dii Consentes gave primacy to the male gods who were free to engage in extramarital affairs while their female consorts were not; this set the paradigm for Roman sexual relationships.

Vesta (the most famous of chaste goddesses) and the other female deities maintained their virtue and honored their consorts, but it would have been considered “unmanly” for the male deities to have done the same. Men were free to and almost expected to engage in extramarital affairs with women, young boys, and other men as long as their partners were not freeborn Roman citizens. Sex was considered a natural and normal aspect of life, and there was no distinction between hetero- or homosexual sex – there was not even a linguistic recognition of the concept of homosexuality being any different than heterosexuality – which could be enjoyed as long as those involved were both willing participants. Festivals such as Lupercalia (celebrating fertility) involved open displays of sexuality and prostitutes were given a place of honor. The state only became involved in sexual matters when someone's choices threatened the status quo. There were four central choices/acts concerning sexuality which, if violated or engaged in, would necessitate legal action:

- Castitas – concerning women who had chosen a life of chastity (such as a Vestal Virgin) and could not rescind that choice without severe penalty, usually death.

- Incestum – violation of a family member, freeborn Roman citizen, Vestal Virgin, or any other individual who had chosen to remain chaste.

- Raptus – kidnapping or abduction with overt or covert intention to engage in sexual relations. Raptus applied even to those who went willingly with their “captors” – such as young women who chose to elope – because they did so without their father's consent.

- Stuprum – rape or sexual misconduct which would include an extramarital affair with a freeborn Roman citizen.

Other than infractions regarding these social mores and taboos, Roman citizens were free to engage in any kind of sexual activity they desired. Problems between partners were their own responsibility to resolve and, if a married couple had a disagreement – regarding a sexual problem or any other – they brought their problem to the goddess Viriplaca (an aspect of Juno whose name literally means “man-placater”) at her temple on the Palatine Hill where it would be addressed. The husband and wife would each explain their problem to the priestess-marriage counselor, and it would be resolved, though more often than not in the husband's favor.

Husbands frequently visited prostitutes in brothels or encountered them at parties or festivals. Prostitution, male and female, was not only legal but considered as natural an aspect of society as employing people to sweep the streets and clean out the latrines. Prostitutes were, naturally, considered low-class individuals, but so were dancers, actors, gladiators, and singers. Respectable social status was reserved for those who fit neatly into the paradigm of the social hierarchy, and those people were always married.

Marriage in Ancient Rome

There was no marriage ceremony as recognized in the modern day. Marriage was only legal between two consenting Roman citizens but “consent” was probably not always given freely. If a father had arranged a marriage for his son or daughter, unless he was incredibly lenient, the child was expected to go through with it even if they would prefer not to. There were three types of marriage recognized as legally binding in Rome:

- Confarreatio (literally “with spelt”) – the typical patrician marriage characterized by a ceremony in which spelt cake and bread was shared. Also known as a manus (hand) marriage because the bride was given by her father's hand to that of the groom.

- Coemptio (“by purchase”) – a plebian marriage in which one purchased one's bride, by one means or another, from her family.

- Usus (“experience” or “use”) – a plebian marriage recognized by long cohabitation by both partners

The following description of a Roman wedding follows the tradition of the confarreatio.

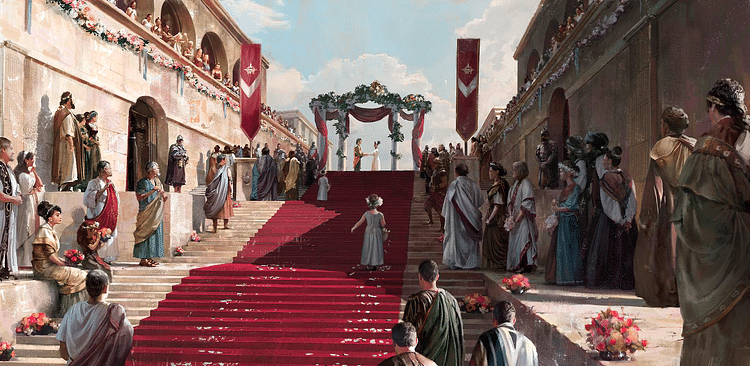

Prior to the wedding, omens were read and the house of the bride's father was decorated with flowers and tapestries. If the omens were good, the ceremony could proceed and the bride and groom were brought together in the public room of the house where the guests would be gathered. Marriage ceremonies usually took place just after sunrise, symbolizing the new life the couple was embarking on.

[The procession] was a public function, that is, anyone might join the procession and take part in the merriment that distinguished it; we are told that persons of rank did not scruple to wait in the street to see a bride. As evening approached, the procession was formed before the bride's house with torch-bearers and flute-players at its head. When all was ready, the marriage hymn was sung and the groom took the bride with a show of force from the arms of her mother. The Romans saw in this custom a reminiscence of the rape of the Sabines, but it probably goes far back beyond the founding of Rome to the custom of marriage by capture that prevailed among many peoples. The bride then took her place in the procession. (Nardo, 78)

The bride, as she walked, would drop one coin dedicated to the spirits of roads (an offering to bring luck to her future path in marriage) and gave two coins to her new husband, one to honor him personally and the other honoring the spirits of his home. As they walked together, the groom threw nuts and sweets into the crowd and the people who followed them scattered the same in return (a ritual remembered in the present day by throwing rice at weddings) until they reached the groom's house.

Once there, the groom would lift his bride over the threshold to carry her in. Johnston suggests that this may also have been “another survival of marriage by capture” (Nardo, 79) but could also have been to prevent the bride tripping and falling or, more likely, was a symbolic gesture removing her from her old life and carrying her easily into her new one. Close friends and family were then invited into the house where the husband offered his new wife fire and water as essential elements of the home and she kindled the first fire in the hearth. Afterwards there was more feasting until the new couple retired for the night.

The minimum legal age for a girl to be married was 12 and, for a boy, 15 but most men married later, around the age of 26. This was because males were thought to be mentally unbalanced between the ages of 15-25. They were thought to be ruled entirely by their passions and unable to make sound judgments. Girls were thought to be far more mature at an earlier age (an accepted fact in the modern day) and so were ready for the responsibilities of marriage when they were, often considerably, younger than the groom.

Conclusion

Marriage was, technically at least, monogamous but divorce was acceptable, no stigma was attached to it, and remarriage was not only equally acceptable but expected. During the time of the Roman Republic (509-27 BCE), divorce was less common than it became in the time of the Empire (27 BCE - 476 CE). The institution of marriage had become unpopular by the time of the empire, the birth rate was down, and Augustus had to enact laws granting special privileges to married couples who produced at least three children.

Although marriage was understood as a societal contract more than an expression of mutual love and respect, there were, no doubt, many loving marriages. The death of the wife in one such union is related by Pliny the Younger (l. 61 - c. 113 CE) in a letter to a friend:

Our friend Macrinus has suffered a heavy blow. He has lost his wife, a woman of exemplary character…He was married to this woman for thirty-nine years without quarrel or offense. This woman treated her husband with the greatest respect and indeed deserved the same in return. So many and so great were the virtues that she exemplified in every stage of her life! Indeed, Macrinus has one great solace in that he had such a good thing for so long. However, I am sure for the same reason he hurts even more because of the knowledge of what he has lost. (Letter 8.5, Harvey, 50)

Although the Roman patriarchy controlled how marriage was defined and observed, and men were expected to have extramarital dalliances, there was still room for honest, loving relationships between husbands and wives based on mutual trust and affection. Women may not have had the kind of equality they were entitled to, but many were still able to live satisfying, contented lives and, often, in the comfort of their husband's love, respect, and admiration.