The legend of Mulan, now world-famous thanks to the Disney films of 1998 and 2020, is the story of a young girl who disguises herself as a man to take her aged father's place as a conscript in the army and so preserve the family honor.

The success of the story hinges on an audience's acceptance of the cross-dressing protagonist and the enduring popularity of the tale – attested to from the Tang Dynasty (618-907 CE) but, more so, from the 16th century CE onwards – would suggest such an acceptance in Chinese society but, in fact, this was not so. Eunuchs were emasculated but did not cross-dress nor were all eunuchs even all that highly respected. Actors, singers, and dancers might cross-dress for a role but they, certainly, were not among the respected professions.

The legend of Mulan, however, probably composed during the Northern Wei Period (386-535 CE) was popular enough to have been revised and rewritten during the Tang Dynasty, preserved in a compilation of the Song Dynasty (960-1279 CE), turned into a popular play in the 16th century CE, and reimagined in other forms in Chinese literature, and then cinema, up through the 1930s, long before the story found an international audience through the 1998 Disney animated film or the recent live-action interpretation of the legend.

Among the most interesting aspects of the legend's acceptance – even its very existence – is why it became as popular as it did when Chinese culture did not encourage women's rights and certainly not gender-fluidity or cross-dressing. Anti-establishment art does not usually find a wide audience until the cultural paradigm changes and yet the legend of Mulan seems to have appealed to the people of China. It is possible that the appeal of the story lies in its handling of gender by linking Mulan's actions with the established virtue of filial piety.

Mulan does not masquerade as a man and join the army on a whim or because she enjoys it but, rather, to save her father and the family's honor. The concept of a strong woman who passes herself off as a man and performs heroic deeds would have been acceptable to a patriarchal society in that the protagonist's actions served to preserve that society and the established cultural paradigm. The woman, in this interpretation, sacrifices herself in order to save her family and preserve honor and such an act would have been seen as not only acceptable but honorable.

It is equally possible, however – and the two are not mutually exclusive – that the legend's popularity derived from how it plays with that very paradigm, turns the accepted norms around, in exploring the meaning of gender – how a man or woman is defined by society – which would have appealed to an audience by couching the message in a fiction, in a work of poetry initially, which would have had the same effect as a satirical comedy in the present day.

Scholars Kwa Shiamin and Wilt. L. Idema suggest that the story's popularity stems from what it suggests concerning societal roles and the questions which arise when one questions one's role. If one accepts their theory, then the story would have transcended any audience's qualms over cross-dressing or gender identity by subtly asking people to consider what role they might be playing in life and which kind they might rather take on instead.

This foundational message of the legend, established by the 16th-century play The Female Mulan, allowed for the story to be fully developed in the late 20th and early 21st centuries through Disney's Mulan films which feature a female protagonist who recognizes that gender and personal identity are not synonymous and, further, that one cannot define one's self by established societal norms.

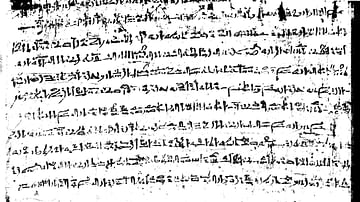

The Poem of Mulan

The story first appears in The Poem of Mulan (also known as The Ballad of Mulan) from the Northern Wei Period. In this earliest version, the king is raising an army for defense against invasion, and Mulan, engaged in the traditionally feminine work of weaving, is troubled because she has seen her father's name on the conscript rolls, knows he is too old to go to war and her brother is too young, and she resolves to go in his place – disguised as his son – to preserve the family's honor. Interestingly, however, the poem does not conclude with a statement on filial piety, personal honor, or nationalism, but makes it clear that the story has been about the equality of the sexes. The following translation is by Thomas Yue:

On and on the spindle creaked

By the door did Mulan weave

Hear not sound of loom and pick

but the sighs of gloom and grief

"Pray tell, girl, what's on your mind?

Something roused your memories?"

"Not at all", Mulan replied,

"'Tis not my mem'ries ailing me.

I saw the notice late last night.

A great army the Khan's raising.

All twelve scrolls of battle rolls.

Father's name from none missing.

My father has no grown-up son,

Nor have I a big brother.

I wish to buy a horse 'n whip.

In his stead I shall go serve."

At north of town she bought the whip

In the south a finest steed

Bit 'n reins from west bazaar

Rug 'n saddle from the east

Leaving home in mid-morning

By night Yellow River reached

Hear not call of home and kins

But the raging river stream

Back on road at break of dawn

At camp she arrived by nightfall

Hear not call of home and kins

But the horses 'cross the wall.

A thousand miles she rode to war

Past went mountains flying by

Golden gongs in northern air

Armors in cold moonlight shined

Ten long years ere her return

From where men fell and countless died

Summoned to the grand palace

By His Majesty on high

Twelve orders of honors earned

Hundred thousands in rewards

"What you desire?", spake the Khan,

"Simply ask and it'll be yours."

"I've no use of high office.

But rather have a fastest horse

— If your Majesty so please —

to take a son home in due course."

Mom 'n dad heard of the news

At the draw-bridge they her expect

Sister hearing Mulan's back

In her best clothes she got dressed

Little brother got the word

A feast to prepare he set

Open'd the door to her room

She sits in bed where she once slept

Off she took her war-time cloak

On she puts her old-time dress

At the mirror she paints her face

By the window she combs her hair

Out she came to greet her mates

Who were caught in great dismay

Twelve years side-by-side they fought

Mulan's a girl not once they thought

Grab a rabbit by its ears

The females squint and the males would kick

While they run loose side-by-side

How could one tell which is it?

Later Versions & Commentary

The poem's narration deals primarily with Mulan's journey to war, survival, and honors bestowed, and her return home but the memorable last lines do not focus on her heroism at all but on how she becomes a woman again simply by putting on women's clothes and make-up. There has been no change in Mulan at all from a heroic soldier to her father's daughter save in her appearance. The soldiers she returned home with are shocked that they fought beside her for years and never once thought she might be a girl and the poem ends by making the clear statement that no one can tell a female rabbit from a male when the two run side by side; in other words, when the two are allowed to do the same exact thing.

The poem was rewritten during the Tang Dynasty to reflect that era's concerns and the original was later preserved in the compilation Collected Works of the Music Bureau during the Song Dynasty. The legend was most likely known through oral tradition but reached its widest audience through the play The Female Mulan by Xu Wei (l. 1521-1593 CE), which fully developed the concept of the original work.

The two-act play begins with a monologue by Mulan setting the scene and source of conflict: the bandit Leopard Skin has launched a rebellion and her father, too old to serve, has been conscripted to serve in the army to defend the Northern Wei kingdom. To preserve the family honor and save her father, she decides to take his place. She purchases what she needs to equip herself and then, in a pivotal scene, unbinds her feet in order to make the transformation from a female to a male. The practice of foot binding began in the 10th century CE during the early Song Dynasty and so its appearance in this play, set in the earlier Northern Wei Period, is an anachronism, but to the audience of Xu Wei's time, it was a well-known symbol of femininity.

Mulan assures the audience that there is no reason for concern because owing to a “secret family recipe” she will be able to return her feet to their petite size and feminine shape once she has completed her time in the army. She then demonstrates her skill with various weapons, showing the audience the completion of her transformation, receives her family's blessing, and leaves her home for the war.

In the second act, she is serving in the army under the name Hua Hu, leads the raid which captures Leopard Skin, and is rewarded with a promotion. She is sent home with two comrades (who, on the way, comment how odd they have found it that they never have seen their friend use the toilet) and, when complimented by them on her bravery, she mocks her accomplishments. Upon reaching her house, she goes in to take off her uniform, apply makeup, and put on one of her old dresses.

She reveals herself as a woman to her comrades, who are suitably amazed, and lets her parents know that she is still a virgin as she shares with them the symbols of her success as a soldier. The neighbor's son, a respected government worker, then appears and it is revealed that he and Mulan have been matched by their parents. The wedding takes place and the play ends with Mulan singing a song alluding to the concluding lines of The Poem of Mulan:

I was a woman till I was seventeen

Was a man for twelve more years.

Passed under thousands of glances.

Which of them could tell cock from hen?

Only now do I believe that a distinction between male

And female isn't told by the eyes.

Who was it really occupied Black Mountain Top?

The girl Mulan went to war for her pop.

The affairs of the world are all such a mess,

Muddling boy and girl is what this play does best. (Shiamin & Idema, xix)

The play is even more forthcoming than the poem regarding the moral of the story: gender does not matter as long as the individual is able to do what needs to be done. The appeal of the legend is its exploration of personal identity. What defines an individual is self-knowledge and self-acceptance expressed through action, performance, the ability to see what needs to be done and do it well, not by social paradigms which can only regulate and restrict the self. Shiamin and Idema comment:

The Female Mulan engages the questions of gender in a much more complicated manner than the “Poem of Mulan”. The play clearly presents a case of performance, and a performance that is crucial both domestically and nationally to Mulan; yet, the character who carries out that performance dismisses her actions completely. Mulan uses the strategies of costume and speech to create a self, mocks the belief that sight can be trusted, and leaves the audience with a conundrum when considering the entire performance. If actions in battle scenes were as if performed by someone else, to whom do we direct our appreciation? Similarly, in watching a play, what constitutes our experience of what happens onstage? Does acting nullify all actions performed under cover of disguise? The Female Mulan suggests that questions of gender or loyalty are not primary considerations. Rather, the play points to more profound questions about how we define ourselves in general: aren't we all simply playing parts? If we are, how do we keep hold of our “true” selves?” (xix-xx)

The answer would seem to be through action - one is what one does – and yet Mulan is able to act as a soldier and then lay aside that persona once she comes home. Mulan is able to resume her former life because she knows who she is. She is able to assume the identity of the soldier Hua Hu, all the while remembering who she actually is, and is then able to pick up her life where she left it by applying her make-up and putting on her old dress. Whatever clothes she wears, whatever gender she assumes, does not matter because she knows who she is.

The innate knowledge of who one is maintains one's identity; what one does in life simply expresses that identity. Artificial rules, regulations, and prohibitions based on gender are shown to be clearly irrelevant – if not silly and actually dangerous – by the legend of Mulan in that the story demonstrates how a girl, prohibited from serving in the army because of gender, is forced to pretend to be a man in order to save her country.

Conclusion

Xu Wei's play put the Mulan legend on the map for the modern era, and other versions of the legend followed from the 17th-20th centuries CE. The most popular version of the 17th century – The Historical Romance of the Sui and Tang – follows the same basic storyline but ends with Mulan killing herself rather than become another concubine in the king's harem. The 19th-century piece – The Complete Account of Extraordinary Mulan – develops the character to a greater extent but concludes the same. In both cases, the point is made that, in spite of Mulan's great achievements, she is still a woman who is seen as an object and must submit to the dominance of men.

The character of Mulan regained her autonomy in the 20th century through the opera (never performed) Mu Lan Joins the Army written in 1903 and the 1939 film Mulan Joins the Army, which emphasizes her superiority to weak, shallow, or cowardly males who cannot serve their country as well as a woman. These pieces, the second especially, replace personal identity with nationalism and the 1939 piece is more propaganda than anything else, shaming men into doing more to serve their country lest they be regarded as inferior to a woman.

The 1998 animated Disney film Mulan returned the heroine to her position as an autonomous individual who directs her own fate, last seen in Xu Wei's play, who refuses to be defined by anyone's standards but her own. At the beginning of this version of the legend, she is not at all sure of what she is to do or whether she is capable of doing it but, by committing to her decision to save her father and serve her country, she becomes what she needs to become and does what needs to be done.

The 2020 film Mulan deepens and expands upon this same theme to present a heroine who understands that personal identity is defined by how one values one's self as well as how one expresses that self to others and has nothing to do with other's opinions or one's gender. This point of view is completely acceptable in the 21st century but not so in ancient China. Mulan's initial popularity, therefore, must be attributed to its appeal to individual, rather than collective, identity: the suggestion that one can do more than play the role society has assigned even as one recognizes the values which have dictated that role.