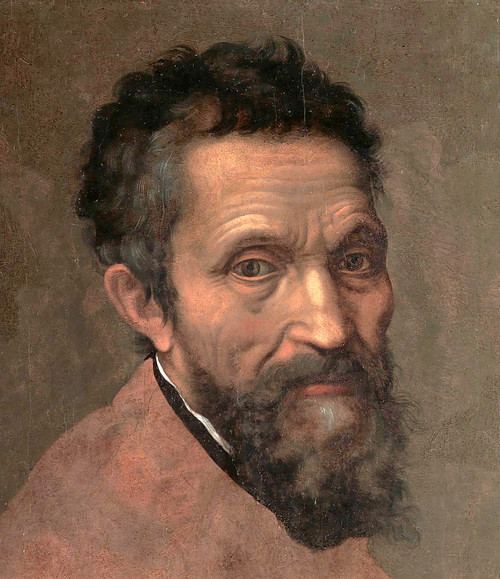

In 1508 CE the Pope commissioned the celebrated Florentine sculptor and painter Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE) to paint scenes on the ceiling of the Vatican's Sistine Chapel. The walls of the chapel had already received decoration from some of the greatest of Renaissance artists, but in four years of toil, Michelangelo would outshine them all with his ambition and technical skill, producing one of the defining works of Western art of any century. The multi-panelled ceiling shows the story of Genesis from the Creation to Noah and the Great Flood. Essentially, the scenes show the creation of humanity, its fall from grace, and ultimate redemption.

The Commission

The Sistine Chapel in the Vatican Palace complex in Rome was commissioned by Pope Sixtus IV (r. 1474-1481 CE). The building was only completed c. 1481 CE but the development of a massive crack in the ceiling in 1504 CE required a repair job that also offered an opportunity to add yet more artwork to an already impressive art-packed interior. What was required was a work to match the excellence of the wall frescoes showing scenes from the lives of Jesus Christ and Moses, which had been created by such masters as Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE) and Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE). One man then stood above all others in the art world, an artist already celebrated for his paintings and sculpture, especially for his massive 1504 CE statue of David, which now stood in the open air of his hometown Florence. This man was Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti, and Pope Julius II (r. 1503-1513 CE) was determined to get him for the job.

Design & Technique

Julius II and Michelangelo had already joined forces when the artist had been commissioned to produce the Pope's tomb. This project, begun in March 1505 CE, had not been a smooth-running one. Patron and artist had quarrelled over the grandiose design that once included 40 marble statues. Contracts were rewritten several times, the design made less and less ambitious, and the work dragged on far beyond the timescale originally envisaged. At one point, Michelangelo described the project as 'the tragedy of the tomb' and he eventually left Rome; his pupils would later finish the job.

In this context, it is easy to see why Michelangelo was far from keen on another project with the Pope, but he finally accepted the most challenging commission of his illustrious career. The contract was signed in May 1508 CE with the commission being to replace the current Sistine Chapel ceiling, which had a painted blue sky and stars. Instead, the project was now to paint figures of the 12 apostles at the sides of the ceiling and fill in the interior with architectural motifs. Michelangelo, however, soon scrapped these plans and went for something much more ambitious, entirely covering a ceiling that measures 39 x 13.7 metres (128 x 45 ft.) and offers an area of nearly 800 square metres.

Over the next four years, the master would work largely alone and very often in an uncomfortable position on top of a bridge-like scaffolding he himself had designed to realise his vision in paint. As the artist progressed, so he moved along the scaffolding from the entrance to his final destination, the altar wall. While the work was ongoing, the artist would let no one see its progress, not even the Pope who was impatient to see the job finished.

In comparison to other similar works of the period, the ceiling was completed remarkably quickly. The frescoes are painted in very bright colours, sometimes in quite large patches. Further, to aid the viewer who must stand several metres below, Michelangelo used the technique of contrasting colours next to each other. This makes some colours appear even brighter than they are and creates a shadow effect, reducing the need for darker and lighter shades of the same colour, a technique that would not be appreciated when viewed from the chapel floor. The artist also uses foreshortening and perspective techniques, fully aware that the intended audience for his work would be looking at the scenes from far below.

The Story of Genesis

The ceiling is an almost overwhelming assembly of Christian imagery. Along the sides of the ceiling are seven prophets and five sibyls, which alternate. According to the Christian tradition, both these groups foretold the coming of Jesus Christ. The five sibyls are representations of those from Delphi, Cumae, Libya, Persia, and Erythrae. The seven prophets are Jonah, Daniel, Isaiah, Zechariah, Joel, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel. Jonah is worth a special mention, as, appearing above the altar and seen with the big fish that swallowed him, Michelangelo has shown the figure seemingly falling backwards, an effect only accentuated by the fact that this particular area of the ceiling bulges forward. Such tricks of perspective can be seen in multiple figures across the ceiling.

Also around the edges, above the windows in the semicircular lunettes, are depictions of the traditional ancestors of Christ. The four larger corner panels contain scenes showing David and Goliath, and Judith and Holofernes at the entrance end, with the Death of Haman, and Moses and the Brazen Serpent at the altar end. The outer edges of the ceiling have slim sections of painted sky to create the illusion that the ceiling contains openings to the outside.

There are nine main central panels running the length of the ceiling. The panels themselves are created by an architectural framework and alternate in two sizes. These panels show a cycle of episodes from the Bible's book of Genesis, narrating the Creation to the time of Noah. Interestingly, the creation of Eve is the central panel, not the creation of Adam, although this may simply be because the scenes are chronological, starting from the altar wall. However, a more convincing argument for Eve's presence in the centre in a work so obviously well-thought-out by the creator is that Eve is being presented as the equivalent or archetype of the Virgin Mary, to whom the Sistine Chapel is dedicated.

Although the chronology of the biblical story begins at the altar wall, in order to view the scenes the right way up, one must face the altar. Consequently, when one enters the room and walks towards the altar, one is actually seeing the story happen in reverse, an intentional rewind effect that returns the viewer back to the point of Creation. At the corners of each of the main panels are four ignudi figures, nudes which have nothing whatsoever to do with the religious narrative but which show Michelangelo's love of boldly rendered figures in dramatic poses. In order, as viewed first from the chapel entrance, the panels are:

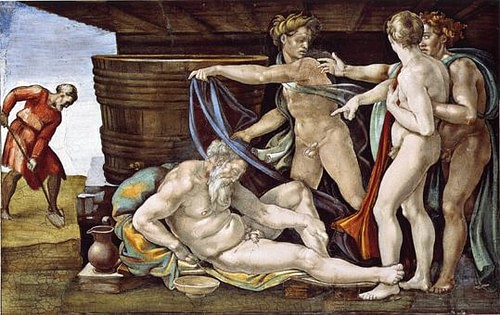

- The Drunkenness of Noah

- The Great Flood

- The Sacrifice of Noah

- Adam & Eve's Temptation and Expulsion from Paradise

- The Creation of Eve

- The Creation of Adam

- God's Separation of Land from Water

- The Creation of the Sun, Moon, and Planets

- God Separates Light from Darkness

There is still some discussion amongst experts regarding the precise identification of some figures. For example, the sacrifice of Noah may in fact be the sacrifice of Abel. The latter interpretation would better fit the chronology of the ceiling as a whole and match the commentaries of Michelangelo's early biographers. At the same time, the relation between Noah and Adam is recognised and reinforced by the artist. The two men have parallel stories as progenitors of humanity and as having fallen from grace. This duplication in events is reflected in Michelangelo's choice to represent Adam and Noah with strikingly similar reclining poses in the panels the Creation of Adam and the Drunkenness of Noah.

The sheer energy of the Creation panels is impressive. The determined face of God, his bent knees, and his swirling robes give ample sign of the force required to create the Sun and planets, which he seems to be hurling into their orbits with his outstretched arms. The Sun is an interesting detail when seen close-up and would easily fit into any impressionist painting. The Creation of Adam panel again has God as a vibrant powerful figure at ease in his element while Adam, in contrast, is shown in a languid pose awaiting a life-giving energy from his maker. The crucial moment when the two fingers touch, just about to happen next in the scene, is given yet more force by the total absence of background features, a veritable chasm between two worlds.

The scale gets bigger and the figures given more space within the panel as one moves from Noah to those panels with God alone, giving another sense of growth and energy to the viewer's experience. By the time we get to the final panel, which is, of course, the first, God has been rendered with much less precision and, almost featureless, he has become a writhing figure of pure energy.

Reception

The work was an immediate success with almost everyone who saw it but there were some rumblings of discontent. The main objection was the amount of nudity and particularly the depiction of genitalia in a handful of figures. This did not stop Michelangelo later being commissioned to paint the entirety of one wall of the chapel with his version of the Last Judgement. Worked on from 1536 to 1541 CE, this fresco was even more controversial than the ceiling. That Jesus did not have his conventional beard and looked a bit younger than usual as well as the appearance of yet more nudity particularly angered some members of the clergy.

In terms of artistic technique, Michelangelo's work in the Sistine Chapel was an important step forward in the development of Western art and was studied by artists throughout the 16th century CE. In the longer measure of subsequent centuries, Michelangelo's work has been appreciated for what it is, the masterpiece of a great artist at the very peak of his powers. The ceiling's central vision of God amongst the clouds reaching out to touch the finger of Adam has become one of the most reproduced images of all time, and the chapel remains one of Italy's most visited attractions.

In the late 20th century CE the ceiling was given a thorough cleaning to remove centuries of smoke residue and dust, which had obscured the fresco behind a thick black mist. A solution was delicately applied using cotton swabs and, little by little, Michelangelo's once-vibrant colouring was returned to its former shining glory.