The Renaissance period witnessed a great renewed interest in the art of antiquity. There was an appreciation of the technical skill required to produce such objects as a Roman marble figure of Venus and an admiration for the form and beauty which medieval art had often ignored. There was, too, an interest from artists eager to learn how best to present the human body and achieve a pleasing sense of proportion in their own new works. Consequently, collectors and artist's workshops accumulated what ancient pieces they could acquire for display or assembled portfolios of drawings of these pieces for study.

With a high demand on the one side and artists producing copies as part of their studies on the other, it was perhaps inevitable that the distinction between original and copy became blurred in the Renaissance art world. Further, copies were not always made to intentionally deceive or make money, many Renaissance artists, even the most famous ones, sometimes tried to pass off objects as antique originals merely to show that they had all of the skills any ancient sculptor had ever possessed. More unscrupulous dealers, though, soon saw the potential profit from producing forgeries, not only of ancient art and inscriptions but also of contemporary art, particularly in the area of printed engravings. Add to these activities the Renaissance fashion for restoring ancient art pieces, which could involve replacing a broken nose, a lost limb or simply restyling the piece to suit changing tastes, and one is left with such fundamental yet perplexing questions as what exactly is an original, restoration, copy or forgery when talking about a work of art?

The Interest in Ancient Art

During the Renaissance, there was a renewed interest in the surviving works of art from ancient Egypt, Greece, and Rome. An appreciation of ancient art was not only cultivated for a love of aesthetics but also to demonstrate one's education, knowledge, and in the case of artefacts from Italian cities, a sense of civic pride. In Italy and France, especially, wealthy art connoisseurs built up collections of antiquities which included statues, relief plaques, pottery, sarcophagi, coins, carved gems, inscriptions, and funerary monuments.

Just as today in many Italian cities with a long history, whenever new housing was built or public engineering projects were carried out during the Renaissance period, so ancient works of art reappeared from their long burial in the ground. Collectors would often create special gardens where these works were displayed for the pleasure of favoured guests, one famous example being that of Lorenzo de Medici (1449-1492 CE) in Florence, a collection which was curated by the noted sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni (c. 1420-1491 CE). In Padua, the artist and workshop owner Francesco Squarcione (1394-1474 CE) had another famous collection which was of great benefit to his apprentices, amongst whom was Andrea Mantegna (c. 1431-1506 CE).

There were even those who wished to systematically catalogue surviving examples of ancient art. Raphael (1483-1520 CE) took a keen interest in the preservation of antiquities and repeatedly requested the popes do more towards their conservation. He even planned to create a detailed map of all Rome's ancient sites but died before he could complete the project. Cataloguing of antiquities was an ongoing process as ancient art was still being discovered on a regular basis. There were even some outstanding and complete or near-complete masterpieces like the Laocoon, discovered in a vineyard outside Rome in 1506 CE. This statue group was only missing one arm, which was restored, and the sculpture was much copied by artists thereafter.

Naturally, ancient artworks were limited in number and tended to remain close to their geographical origin or place of discovery. Even illustrious collectors like Isabella d'Este (1474-1539 CE), wife of Gianfrancesco II Gonzaga (1466-1519 CE), then ruler of Mantua, struggled to find the pieces they wanted. Despite sending out teams of buyers across Italy and Greece and possessing what she described as a "hunger for antiquities" (Wyatt, 53), Isabella was often obliged to settle for smaller replica pieces sculpted in bronze. For those of more modest means, an alternative was to purchase plaster casts of antique originals or small bronze plaques that re-represented classical works in a different format.

Reusing the Past

Artists studied ancient pieces to better understand how they themselves might reproduce the human form and proportions in stone, metal, and paint. This knowledge was known as the doctrina or teachings of the masters from antiquity. During the Renaissance, disegno, in particular, was a popular technique where artists learnt to draw by copying pieces of ancient art using chalk, charcoal, and paper. For those trainees without direct access to antiquities, some masters under whom they studied provided portfolios of drawings, catalogues of the best pieces of ancient sculpture and art. Jacopo Bellini (c. 1400 - c. 1470 CE) had a famous album of such drawings, which is today in the Louvre museum, Paris. Certainly, many faces and poses in antique art found their way into Renaissance artworks. Sometimes the imitation was direct as in the (now lost) Sleeping Cupid by Michelangelo (1475-1564 CE), based on the Hellenistic Eros. At other times it was more subtle when, for example, a dying Greek hero on a Roman sarcophagus might easily become the body of Christ after the crucifixion in a Renaissance painting. Some poses became so common they acquired specific names. For example, the Venus pudica was the classical pose of the goddess Venus covering her nakedness with her hands, and it is seen everywhere in Renaissance art but perhaps most famously in the Birth of Venus painting by Sandro Botticelli (1445-1510 CE).

Another area where original and new works of art overlapped was restoration. Unlike today, perhaps, where the fashion is to admire ancient works only in their original form whatever poor condition they might be in, Renaissance collectors often wanted a piece to look its very best. Consequently, broken pieces - especially noses, hands, limbs, or even heads - were restored or replaced (or substituted using pieces from other ancient works). There might even be some restyling, changing the hair, for example. Lorenzo de Medici's collection, depending on your viewpoint, benefitted or suffered from this restoration approach.

Another lucrative addition to an ancient statue besides a new nose was to add an inscription. These could be made in the scripts of the ancient world (or what looked like them) such as Etruscan or Egyptian hieroglyphs. The seller could then market the piece as having a particularly apt inscription personally relevant to a particular client. At that time, many ancient scripts were as yet to be deciphered and so the seller was free to offer any interpretation he wished on his carefully carved symbols.

Outright Forgeries

Some artists went even further than copying or reworking classical iconography and carved entire pieces of sculpture which imitated the ancient pieces. It did not take long for some unscrupulous workshop owners to realise that the high prices commanded for an antique piece that was already heavily restored might be easily beaten by an entirely new piece that appeared to be antique and was intact. Give the work a little ageing, scratches, or some minor intentional damage, and few would spot the forgery. Further, some forgers even convinced a prospective client by staging a false excavation where the fake was dug up from the earth in a thrilling new discovery. Then there were those clients who did not want a pristine statue but yearned for a patina of antiquity. Lorenzo de' Medici, for example, once instructed Michelangelo to bury a marble cupid in the earth for a while so that it might acquire a more desirable aged look. Just as the Christian church had been promoting holy relics of dubious origin for centuries, it was not perhaps as important as we might think today that a piece of art was original, only that people believed it was.

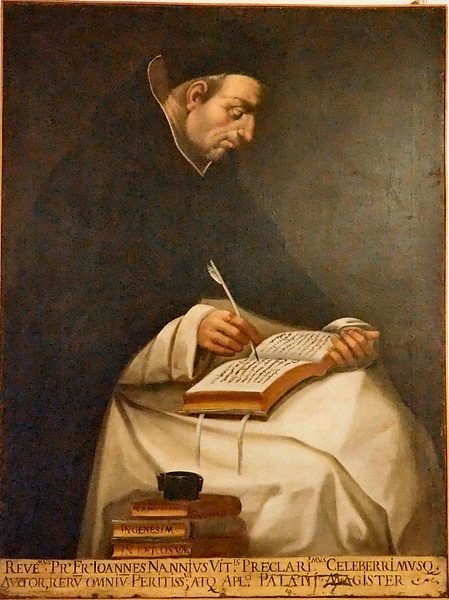

One of the most prolific of the Renaissance forgers was the scholar and Dominican friar Annio da Viterbo (c. 1432-1502 CE). Annio was nothing if not versatile, and he produced a series of fake inscriptions in various alphabets from Egypt, Babylon, Greece, and Rome. Nor was he limited in ambition as many of his 'lost fragments' were supposed to be the works of such famous names from antiquity as Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE - c. 50 CE) and Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE). In addition to the outright fakes, Annio was one of those not shy to add an inscription or two to genuine antique pieces to increase their significance. In all fairness to Annio, while he took the money and ran (or in his case, it was more about court favours), he was also interested in civic pride and promoting the Etruscan history of his hometown of Viterbo, as well as establishing the importance of the Etruscans over the Greeks and Romans. Historical, political and religious motives for 'faking texts' was far from being a new phenomenon. Further, Annio did have a collection of genuine artefacts, and these he conserved and curated for public show. Scholars debated even then what was and what was not authentic in the collection, but its catalogue, the 1498 CE Antiquitates, remained an influential work right into the 18th century CE.

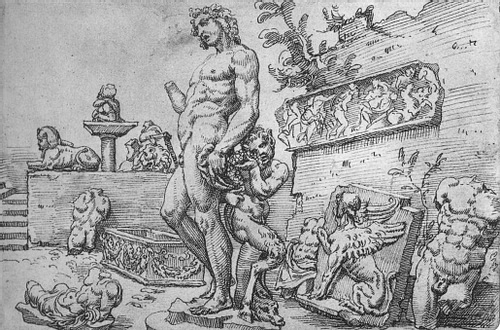

Deceptions regarding authenticity were not always carried out for monetary gain. Michelangelo, for example, was keen to show that he was just as good a sculptor as anyone from antiquity and made several imitations of antique pieces. In 1496 CE, he famously sculpted the Sleeping Cupid mentioned above, which he purposely aged to make it appear an authentic ancient work and which he then successfully sold through a dealer to Cardinal Raffaele Riario. Michelangelo did later reveal the ruse to the cardinal. Riario's banker was Jacopo Galli, and he had his own collection of antique sculptures. In the midst of these statues stood Michelangelo's Bacchus, a challenge to any viewer to distinguish the new from the old.

The Market for Prints

Woodblock printing began around 1420 CE in Europe but it was the use of metal plates later in the same century that elevated printing to a new level. Copper-plate engraving allowed for much more precise and detailed prints, and it became a highly specialised and technically accomplished art form during the Renaissance. This allowed the great works of Renaissance art (and their producers) - whether it be a painting, sculpture, or fresco - to be legitimately copied and become more widely known. Engravings were sent across Europe so that artists could study and non-travellers appreciate the new original works of art then appearing elsewhere. The most famous producer of prints was Marcantonio Raimondi (1480-1534 CE), who was originally from Bologna but most active in Rome.

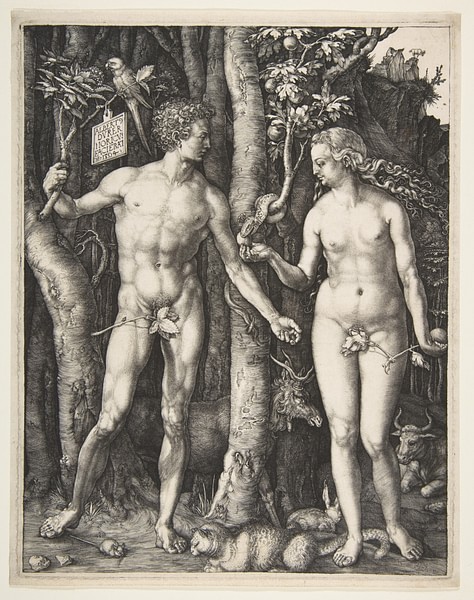

Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519 CE), and Raphael were all beneficiaries of this popular spreading of art via prints. Indeed, even original works by Michelangelo were being collected during his lifetime, especially in France. Such famous artists as the German Renaissance painter Albrecht Dürer (1471-1528 CE) were especially keen to build up a portfolio of sketches and prints of fellow artists elsewhere. Sometimes, works were reproduced or used as inspiration for an entirely different medium, such as prints of Raphael's Acts of the Apostles fresco in the Vatican which were used by craftworkers in Belgium to produce tapestries. Prints certainly spread artistic ideas, and the traffic was not always from Italy to elsewhere as Dürer's work, for example, became known and imitated in Italy largely thanks to engravings. In the 16th century CE, European engraved prints found their way across Asia via Italian, Spanish, and Portuguese traders and missionaries who took them for sale or as gifts to the royal courts they served. Akbar the Great, Emperor of the Mughal Empire (r. 1556-1605 CE), was particularly fond of Renaissance prints and ordered his own court artists such as the great Basawan to copy them or rework originals. Similarly, in Japan the Italian missionary Giovanni Niccolo established an academy in Nagasaki where western painting and engraving techniques were taught.

A great level of expertise was required to engrave copper plates with precision and finesse. For this reason, fine prints, when made from plates carved by such superb draughtsmen as Andrea Mantegna, became collector's items in themselves from around 1500 CE. As a consequence, there then emerged a market for fake prints claiming to have come from plates made by a celebrated engraver. To combat this, artists generally kept ownership of the original plates, and not the printer. Further, legitimate printers such as Raimondi tended to monogram their prints to indicate which printer had made them, and a note was added to acknowledge the original inventor of the subject matter. Thus, for example, a print of a drawing by Raphael might have the following printed in the bottom corner: Rapha[el] Urbi[nas] inven[it]. The fact that such printers as Raimondi bothered to do this suggests that many unscrupulous printers making illegitimate copies did not.

Copying Renaissance Art

Not only were ancient art objects and contemporary prints copied but Renaissance works might be faked, too. Such was the demand for fine art and such were the prizes on offer for securing lucrative contracts to produce art for rich and famous patrons, some Renaissance artists tried to claim the work of others. Michelangelo's Pietà, completed between 1497 and 1500 CE, was claimed by one unscrupulous artist as his own, which led to the master creator having to later sign the sculpture himself.

As the Renaissance progressed and the middle classes became richer, so art became within their means. Workshops like the ones run by the Florentine sculptor Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455 CE) began not exactly to mass-produce art but to at least employ standardised elements taken from an existing catalogue. Such standard poses as the Madonna and Child could appear in many forms of sculpture, for example. Similarly, the workshop managed by Pietro Perugino (c. 1450-1523 CE) in Perugia produced paintings for altar panels based on a number of standardised in-house drawings of poses and faces. This repetition, even if well-disguised through assortment, was another area that could be exploited by the makers of copies and those trying to sell a piece of art as made by somebody other than the original manufacturer.

Finally, the temptation for famed artists to take on more commissions than they could handle and their regular use of assistants to finish off works they themselves signed blurred even more the landscape of Renaissance art. Was it now really necessary for a work of art to be produced by a single artist using unique ideas? The more collaborative art became and the more repetitious the motifs, so the opportunities for making copies increased.

Even today, with our ability to examine works of art using all manner of technologies, it often remains difficult to ascertain exactly when, where, and by whom a specific painting was produced. If experts today cannot determine whether a painting was created by Gentile Bellini (c. 1429-1507 CE) or Giovanni Bellini (c. 1430-1516 CE) or if the face of a painting was really executed by Raphael or one of his assistants, then little wonder that Renaissance copyists tried their luck at passing off seemingly inferior works as those made by the hand of a genuine master.