The unicorn, a mythical creature popularized in European folklore, has captivated the human imagination for over 2,000 years. For most of that time, well into the Middle Ages, people also believed them to be real. The roots of the unicorn myth date back at least as far as 400 BCE, when the Greek historian Ctesias first documented a unicorn-like animal in his writings on the region of India. Descriptions of the unicorn can be traced throughout the following centuries in the writings of other prominent historical figures, such as Aristotle, Pliny the Elder, and even Julius Caesar, who claimed that similar animals could be found in the ancient and vast Hercynian Forest of Germany.

These early accounts describe the unicorn as ferocious, swift, and impossible to capture, with a magical horn capable of healing numerous ailments. Over time, the unicorn acquired additional significance as a symbol of purity, protection, and medieval chivalry. It even developed religious connotations, sometimes employed as an allegory for Christ. During the Middle Ages, unicorn imagery and descriptions were commonly included in medieval bestiaries, and the unicorn became a popular motif in medieval art. Perhaps the most famous example is The Unicorn Tapestries, currently housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art's Cloisters in New York City. Today, the unicorn can still be found everywhere (and nowhere): it remains a ubiquitous symbol that pervades popular culture from children's movies to Silicon Valley slang for start-ups valued at over one billion dollars. Though we may no longer believe in the existence of unicorns, the unicorn myth remains very much alive and well.

Early Descriptions of a One-Horned Beast

The earliest written description of a unicorn is attributed to Ctesias in 400 BCE. A Greek physician and historian who served in the court of both Darius II (r. 424-404 BCE) and Artaxerxes II (r. 404-358 BCE) of the Achaemenid Empire, Ctesias wrote Indica, the first book in Greek on the regions of India, Tibet, and the Himalayas. Having never been to that region himself, however, he relied on information brought to him by travelers along the Silk Road. Indica was both widely read and quoted; it was also ridiculed for some of its more fanciful descriptions. It survives today only in the work of others, including fragments summarized by Photius in the 9th century CE. The first mention of a unicorn-like animal appears in the 25th fragment:

There are in India certain wild asses which are as large as horses and even larger. Their bodies are white, their heads dark red, and their eyes dark blue. They have a horn in the middle of the forehead that is one cubit [about a foot and a half] in length; the base of this horn is pure white…the upper part is sharp and of a vivid crimson, and the middle portion is black. Those who drink from these horns, made into drinking vessels, are not subject, they say, either to convulsions or to the falling sickness. Indeed they are immune even to poisons if, either before or after swallowing such, they drink wine, water, or anything else from these beakers… (Freeman, 14)

This colorful animal that Ctesias describes is most likely a fanciful rendition of the Indian rhinoceros. The rhinoceros horn was considered in India to have healing properties and was sometimes made into drinking vessels decorated with three bands of color. Even so, the belief in the magical healing powers of the unicorn horn was to become an integral component of the unicorn myth. Ctesias continues:

This animal is exceedingly swift and powerful, so that no creature, neither horse nor any other, can overtake it…There is no other way to capture them in the hunt than this: when they conduct their young to pasture, if they are surrounded by many horsemen, they refuse to flee, thus forsaking their offspring. They fight with thrusts of horn; they kick, bite, and strike with wounding force both horses and hunters; but they perish under the blows of arrows and javelins, for they cannot be taken alive. The flesh of this animal is so bitter that it is not edible; it is hunted for its horn and its ankle-bone. (Freeman, 14)

Ctesias, who was known for having a personal interest in the fantastical, had described a captivating creature unlike any other. It is this definition that influenced future historians and became the foundation upon which the myth of the unicorn was built. Writing less than a century later, Aristotle criticized Ctesias's work for its perceived embellishments, but he did not dispute Ctesias's description of this single-horned beast. In The History of Animals, Aristotle confirms the existence of the "Indian ass," an animal he describes as having a single horn protruding from the center of its head, and adds that unlike most horned animals, the Indian ass is "single-hooved," as opposed to "cloven-footed."

Julius Caesar, writing circa 50 BCE, records the existence of a stag with a single horn, much "taller and straighter" than any seen before, living in the ancient and dense Hercynian Forest of Germany. The Roman historian Aelian, writing in the 2nd century CE, describes the unicorn much in the same way as Ctesias, noting that it can be found in India. Aelian, however, describes their coats as reddish in color, not white. Their horns are black, he says, and spiral up to a very sharp point. They are gentle with other animals but prefer solitude, and only mingle with others of their kind during mating season. He notes that they cannot be captured, at least not when they are full-grown, and that drinking from their horns will cure ailments.

These accounts by prominent historical figures, deemed trustworthy and reputable in their time, helped to perpetuate the unicorn myth through the centuries. It was Pliny the Elder who, in the 1st century CE, finally gave this single-horned animal the name by which we know it today: the monocerous, or unicorn. Though he describes it as horse-like with a single horn, Pliny says that it has the feet of an elephant and the tail of a boar. The monocerous is extremely powerful and, of course, cannot be captured alive. Though physical descriptions of the unicorn continued to vary in these early writings, the character of the animal remained constant. These early accounts outlined the qualities that came to be associated with the mythological unicorn: speed, ferocity, invincibility, healing powers, and elusiveness.

The Unicorn as a Religious Symbol

Throughout the ensuing centuries, the unicorn acquired religious connotations within the Christian church as a symbol of purity and grace, sometimes used as an allegory for Christ. During the 3rd century CE, Alexandrian scholars translating the Old Testament from Hebrew to Greek replaced the Hebrew word re êm, meaning wild ox, with the Greek word monoceros. Due to this translation, the word "unicorn" appears in some English translations of the Bible, including the King James Bible, often with references to strength and ferocity.

The Unicorn in Medieval & Early Renaissance Art

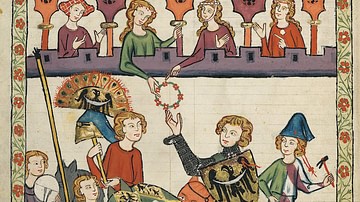

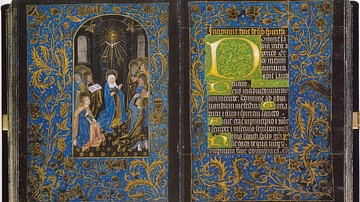

So great was the medieval fascination with unicorns that narwhal tusks were frequently passed off as unicorn horns, and sold for large sums of money by traders. The popularity of the unicorn was also aided by the proliferation of the medieval bestiary. Preceded by the Greek Physiologus, bestiaries were illustrated books of the natural world containing descriptions of all sorts of animals, plants, and rocks, some real and others only imagined but nonetheless believed by contemporary readers to exist in the natural world. The unicorn is most commonly found in bestiaries and other illuminated manuscripts of the 12th and 13th centuries CE and is often depicted beside a young woman. Deriving from its association with purity and chastity, the medieval unicorn was believed to have a fondness for young maidens. While Ctesias and other earlier writers described the unicorn as being virtually impossible to capture alive, it was later thought that young women, specifically virgins, were capable of taming unicorns and assisting in their capture. Some art historians have pointed out the phallic nature of the unicorn's horn when remarking on this particular association. This relationship can be seen in many of the images from surviving bestiaries.

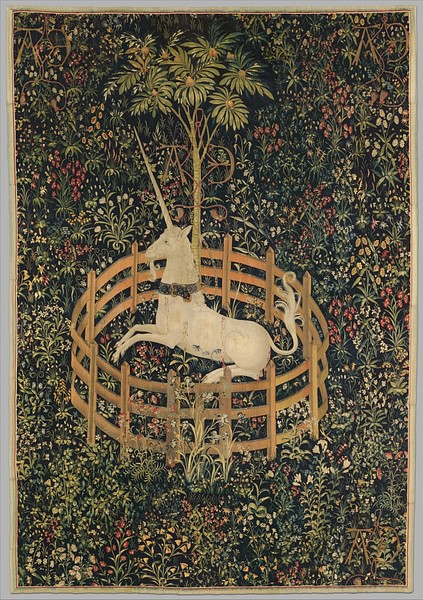

The characteristics that had come to be associated with the unicorn by the late Middle Ages are evident in The Unicorn Tapestries, a series of seven tapestries housed at the Met Cloisters that depict a unicorn hunt. Thought to have been woven over a ten-year period from 1495 to 1505 CE, they were discovered in the possession of François VI de La Rochefoucauld in 1680 CE. Though each tapestry is sometimes called by different names, the Met currently refers to them as follows:

- "The Hunters Enter the Woods"

- "The Unicorn Purifies Water"

- "The Unicorn Crosses a Stream"

- "The Unicorn Defends Himself"

- "The Unicorn Surrenders to a Maiden"

- "The Hunters Return to the Castle"

- "The Unicorn Rests in a Garden"

In this tapestry series, we can see the unicorn's healing powers as it cleanses the drinking water for the other animals, its ferocity as it defends itself from the hunters, and its susceptibility to the powers of a young maiden. Though this specific tapestry survives only in fragments, we can still see that the unicorn is docile in the presence of the young maiden, oblivious to the hunter holding a horn who lurks in the woods, ready to alert his fellow hunters. There is some speculation as to whether the seventh tapestry, "The Unicorn Rests in a Garden," was originally part of this series, but these tapestries as they currently hang demonstrate the unicorn's power of everlasting life, as we see the unicorn killed, but then later, alive and well.

The Search for the Ancient Unicorn

Like in ancient times, there are few, if any, who would seriously claim to have seen a unicorn, but that has not stopped us from looking. There has been some temptation on the part of modern scholars to search for evidence of the enigmatic unicorn in far more ancient imagery than medieval bestiaries. The so-called unicorn cave painting found in the Hall of the Bulls at the Paleolithic Lascaux Cave dates back to 17000 BCE, for example. There is also the "unicorn" that appears on many of the soapstone seals from the Indus Valley Civilization (c. 7000 to c. 600 BCE), recovered at archaeological sites in South Asia.

Perhaps these animals initially referred to a creature similar to the unicorn, which would mean that the roots of the unicorn myth date back much, much farther than evidence currently suggests. Many historians, however, dispute that such depictions are anything more than two-horned animals rendered in profile. Additionally, the Chinese qilin has sometimes been compared to the unicorn of European medieval folklore, although traditionally the qilin is depicted as having two horns, and it would be difficult to find many similarities between the two creatures. Either way, it is not simply having a single horn that makes the mythical unicorn so fascinating, but the characteristics that have come to be associated with this elusive, fearsome, and magical creature. The unicorn has captured our attention for centuries, but it is only through art and stories that we, in turn, have ever come close to capturing a unicorn.