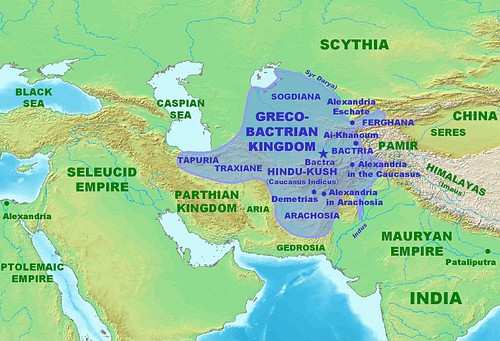

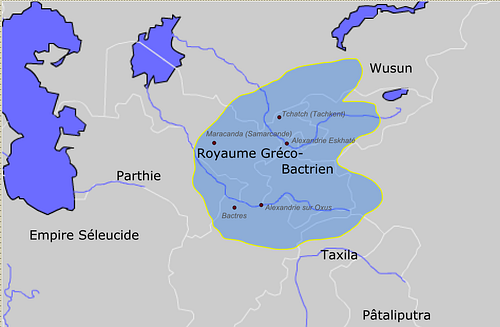

The rarity of the appearance of Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms in ancient literature is one of the reasons why those states are so little-known today. Indo-Greek literature did exist, but none has been found that speaks about the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek states. Classical authors tell us very little about Indo-Greek kingdoms, as they were far away from the Mediterranean world, cut off from other Greeks by the mighty Parthian state. Indian classical literature almost never interested itself in events, except from a religious point of view, and thus does not help to solve the dilemma. Chinese accounts exist, but only supply us with limited information.

Almost all of what remains today of ancient litterature about those kingdoms can be summarized on one page, which is what this article is going to accomplish.

NB: These are only quotes about the Greco-Bactrian and Indo-Greek kingdoms, and not about Bactria the area.

Greek Sources

When the news came that Euthydemus with his army was before Tapuria, and that ten thousand cavalry were in his front guarding the ford of the river Arius, Antiochus decided to abandon the siege and deal with the situation. The river being at a distance of three days' march, he marched at a moderate pace for two days, but on the third day he order the rest of his army to break up their camp at daylight while he himself with his cavalry, his light-armed infantry, and ten thousand peltasts advanced during the night marching quickly. For he had heard that the enemy's horse kept guard during the day on the river bank, but retired at night to a town as much as twenty stades away. Having completed the remainder of the distance during the night, as the plain is easy to ride over, he succeeded in getting the greater part of his forces across the river by daylight. The Bactrian cavalry, when their scouts had reported this, came up to attack and engaged the enemy while still on the march. The king, seeing that it was necessary to stand the first charge of the enemy, called on one thousand of his cavalry who were accustomed to fight round him and ordered the rest to form up on the spot in squadrons and troops and all place themselves in their usual order, while he himself with the force I spoke of met and engaged the p225Bactrians who were the first to charge. In this affair it seems that Antiochus himself fought more brilliantly than any of those with him. There were severe losses on both sides, but the king's cavalry repulsed the first Bactrian regiment. When, however, the second and third came up they were in difficulties and had the worst of it. It was now that Panaetolus ordered his men to advance, and joining the king and those who were fighting round him, compelled those Bactrians who were pursuing in disorder to turn rein and take to headlong flight. The Bactrians, now hard pressed by Panaetlus, never stopped until they joined Euthydemus after losing most of their men. The royal cavalry, after killing many of the enemy and making many prisoners, withdrew, and at first encamped on the spot near the river. n this battle Antiochus's horse was transfixed and killed, and he himself received a wound in the mouth and lost several of his teeth, having in general gained a greater reputation for courage on this occasion than on any other. After the battle Euthydemus was terror-stricken and retired with his army to a city in Bactria called Zariaspa.

(Polybius, Histories, X, 49, between 167-157 BCE. Translation: H. J. Edwards 1922)

For Euthydemus himself was a native of Magnesia, and he now, in defending himself to Teleas, said that Antiochus was not justified in attempting to deprive him of his kingdom, as he himself had never revolted against the king, but after others had revolted he had possessed himself of the throne of Bactria by destroying their descendants. After speaking at some length in the same sense he begged Teleas to mediate between them in a friendly manner and bring about a reconciliation, entreating Antiochus not to grudge him the name and state of king, as if he did not yield to this request, neither of them would be safe; for considerable hordes of Nomads were approaching, and this was not only a grave danger to both of them, but if they consented to admit them, the country would certainly relapse into barbarism. After speaking thus he dispatched Teleas to Antiochus. The king, who had long been on the look-out for a solution of the question when he received Teleas' report, gladly consented to an accommodation owing to the reasons above stated. Teleas went backwards and forwards more than once to both kings, and finally Euthydemus sent off his son Demetrius to ratify the agreement. Antiochus, on receiving the young man and judging him from his appearance, conversation, and dignity of bearing to be worthy of royal rank, in the first place promised to give him one of his daughters in marriage and next gave permission to his father to style himself king. After making a written treaty concerning other points and entering into a sworn alliance, Antiochus took his departure, serving out generous ratons of corn to his troops and adding to his own the elephants belonging to Euthydemus.

(Polybius, Histories, XI, 34.1-10, between 167-157 BCE. Translation: H. J. Edwards 1922)

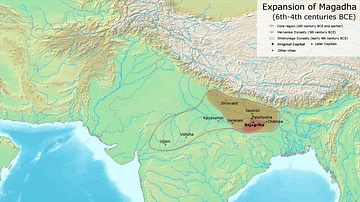

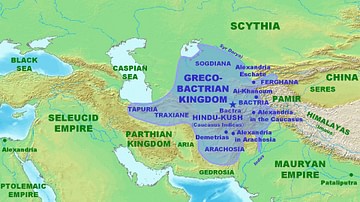

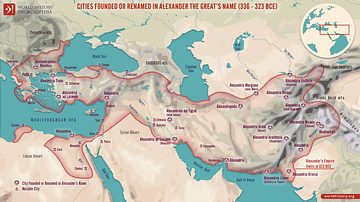

The Greeks who caused Bactria to revolt grew so powerful on account of the fertility of the country that they became masters, not only of Ariana, but also of India, as Apollodorus of Artemita says: and more tribes were subdued by them than by Alexander—by Menander in particular (at least if he actually crossed the Hypanis towards the east and advanced as far as the Imaüs), for some were subdued by him personally and others by Demetrius, the son of Euthydemus the king of the Bactrians; and they took possession, not only of Patalena, but also, on the rest of the coast, of what is called the kingdom of Saraostus and Sigerdis. In short, Apollodorus says that Bactriana is the ornament of Ariana as a whole; and, more than that, they extended their empire even as far as the Seres and the Phryni. Their cities were Bactra (also called Zariaspa, through which flows a river bearing the same name and emptying into the Oxus), and Darapsa, and several others. Among these was Eucratidia, which was named after its ruler. The Greeks took possession of it and divided it into satrapies, of which the satrapy Turiva and that of Aspionus were taken away from Eucratides by the Parthians. And they also held Sogdiana, situated above Bactriana towards the east between the Oxus River, which forms the boundary between the Bactrians and the Sogdians, and the Iaxartes River. And the Iaxartes forms also the boundary between the Sogdians and the nomads.

(Strabo, Geography, XI. 11.1-2, between15/10 BCE and 24 CE. Translation: Horace Leonard Jones 1917)

At any rate, Apollodorus, who wrote The Parthica, when he mentions the Greeks who caused Bactriana to revolt from the Syrian kings who succeeded Seleucus Nicator, says that when those kings had grown in power they also attacked India, but he reveals nothing further than what was already known, and even contradicts what was known, saying that those kings subdued more of India than the Macedonians; that Eucratidas, at any rate, held a thousand cities as his subjects.

(Strabo, Geography, XV.3,between15/10 BCE and 24 CE. Translation: Horace Leonard Jones 1917)

Latin sources

...and the most powerful dominion of Bactria, peopled with a thousand cities...

(Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, XLI 1.8, IIe CE. Translation: John Selby Watson 1853)

Diodotus, the governor of the thousand cities of Bactria, defected and proclaimed himself king; all the other people of the Orient followed his example and seceded from the Macedonians.

(Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, XLI 4.5, IIe CE. Translation: John Selby Watson 1853)

Not long after, too, he (Arsaces) made himself master of Hyrcania, and thus, invested with authority over two nations, raised a large army, through fear of Seleucus and Theodotus, king of the Bactrians. But being soon relieved of his fears by the death of Theodotus, he made peace and an alliance with his son, who was also named Theodotus; and not long after, engaging with king Seleucus, who came to take vengeance on the revolters, he obtained a victory.

(Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, XLI 4.8-9, IIe CE. Translation: John Selby Watson 1853)

Almost at the same time that Mithridates ascended the throne among the Parthians, Eucratides began to reign among the Bactrians; both of them being great men. But the fortune of the Parthians, being the more successful, raised them, under this prince, to the highest degree of power; while the Bactrians, harassed with various wars, lost not only their dominions, but their liberty; for having suffered from contentions with the Sogdians, the Drangians, and the Indians, they were at last overcome, as if exhausted, by the weaker6 Parthians. Eucratides, however, carried on several wars with great spirit, and though much reduced by his losses in them, yet, when he was besieged by Demetrius king of the Indians, with a garrison of only three hundred soldiers, he repulsed, by continual sallies, a force of sixty thousand enemies. Having accordingly escaped, after a five months' siege, he reduced India under his power. But as he was returning from the country, he was killed on his march by his son, with whom he had shared his throne, and who was so far from concealing the murder, that, as if he had killed an enemy, and not his father, he drove his chariot through his blood, and ordered his body to be cast out unburied.

(Justin, Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus, XLI 6.1-5, IIe CE. Translation: John Selby Watson 1853)

Indian sources

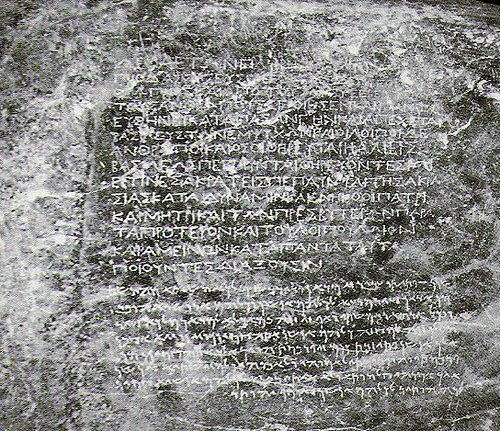

This Garuda pillar of Vasudeva, the God of Gods

was erected here by Heliodoros, a worshipper of Vishnu (Bhagavata),

the son of Dion, and an inhabitant of Taxila,

who came as Greek (Yona) ambassador from the Great King

Antialkidas to King Kosiputra Bhagabhadra, the Saviour

then reigning propserously in the 14th year of his kingship.

Three immortal precepts when practised lead to heaven

self-retraint, charity, conscientiouness.

(Heliodoros, Greek ambassador of king Antialkidas, on the Vidisha pillar, c.110 BCE. Text in Brahmi script. Translation by Tarn 1957 plate VI)

Then in the eighth year, (Kharavela) with a large army having sacked Goradhagiri causes pressure on Rajagaha (Rajagriha). On account of the loud report of this act of valour, the Yavana (Greek) King Dimi[ta] retreated to Mathura having extricated his demoralized army.

(Hatigumpha Inscription, line 8, probably in the 1st century BCE. Original text is in Brahmi script. The king "Dimita" could be Demetrios I, or Menander, general of Demetrios II (Widemann's thesis). Translation in Epigraphia Indica 1920)

After having conquered Saketa, the country of the Panchala and the Mathuras, the Yavanas (Greeks), wicked and valiant, will reach Kusumadhvaja. The thick mud-fortifications at Pataliputra being reached, all the provinces will be in disorder, without doubt. Ultimately, a great battle will follow, with tree-like engines (siege engines).

(Gargi-Samhita, Yuga Purana, V. Translation; J. Mitchiner 1976)

The Yavanas (Greeks) will command, the Kings will disappear. (But ultimately) the Yavanas, intoxicated with fighting, will not stay in Madhadesa (the Middle Country); there will be undoubtedly a civil war among them, arising in their own country (Bactria), there will be a terrible and ferocious war.

(Gargi-Samhita, Yuga Purana, VII. Translation; J. Mitchiner 1976)

The Yavanas were besieging Saketa. The Yavanas were besieging Madhyamika (the "Middle country").

(Patanjali, Mahābhāsya, c.150 BCE, two exemples of the use of the perfect tense denoting a recent event)

Chinese sources

Southeast of Daxia is the kingdom of Shendu (India)... Shendu, they told me, lies several thousand li southeast of Daxia (Bactria). The people cultivate the land and live much like the people of Daxia. The region is said to be hot and damp. The inhabitants ride elephants when they go in battle. The kingdom is situated on a great river (Indus).

(Sima Quina, Shiji, 123, written between 109 and 91, on the report of Zhang Qian between c.134 and 125 BCE. Note: North-West India was ruled by the Indo-Greek at this time, which is what the "like the people of Daxia" refers to. Translation: Burton Watson 1961)

The Kingdom of Gaofu (Kabul) is southwest of the Da Yuezhi (Kushans). It is also a large kingdom. Their way of life is similar to that of Tianzhu (Northwestern India), but they are weak and easy to subdue. They are excellent traders and are very wealthy. They have not always been ruled by the same masters. Whenever one of the three kingdoms of Tianzhu (Northwestern India), Jibin (Kapisha-Peshawar), or Anxi (Parthia) became powerful, they took control of it; when weakened, they lost it.

(Fan Ye (398-445 CE), Hou Han Shu (The History of the Later Han) 88, Xiyu juan, 14. Note that Fan Ye made a compilation of ancient Chinese writers, and for this section those precedents writers belong to the Ist century AD. Kingdom of Gaofu may have been Indo-Greek or Indo-Saka one, but the one of Jibin was probably the last Indo-Greek kingdom of Alexandria Kapisa. translation: John E. Hill 2003)

It still remains to quote the Milindapañhā, "Questions of Milinda", a buddhist text from c.100 BCE in which the Indo-Greek king Menander (Milinda) has a dialogue with the sage Nagāsena. But because all this dialogue is highly religious, none of it can be taken seriously about this king and his kingdom in the text. To get a better idea, here is an abridged version from 2001.