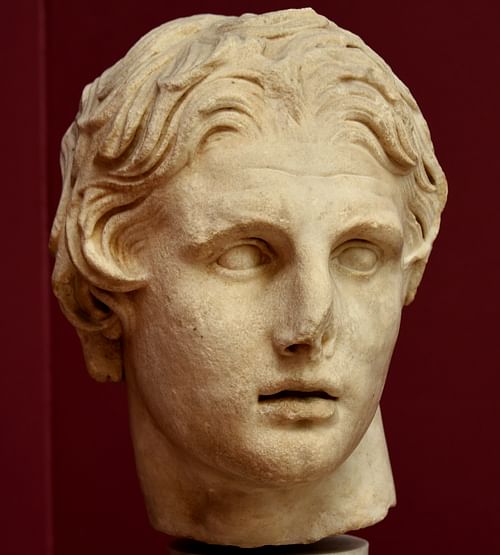

The so-called Hyphasis Mutiny was a conflict between Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE) and his army following their victory at the river Hydaspes in 326 BCE. Alexander voiced plans for further conquests in the Indian subcontinent, however, when his men reached the river Hyphasis, there was an open revolt. The mutiny ended with Alexander giving in to his men's wishes and turning back; he did not venture further into the Indian subcontinent as he intended. Over the years, historians have examined the importance of this moment of tension between a king and his army. This includes the issue of whether the term “mutiny” can truly apply to this incident.

The Indian Campaign

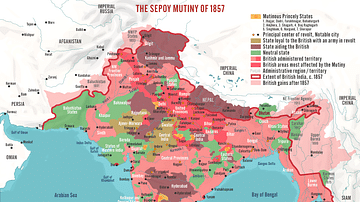

When Alexander marched across the Hindu Kush to India in 327 BC, the denizens of Bazira feared for their lives, fled to the Aornos Rock, reputed to be impregnable so that not even Heracles was able to capture it. Alexander had difficulty getting to the rock and started building a mound, then gained a foothold on a hill. When the Indians noticed the Macedonians closing in, they surrendered. Alexander placed a garrison on the abandoned portion of the Aornos Rock.

The city of Nysa asked Alexander to recognize their freedom and independence, which Alexander granted and made allies of them, acquiring 300 horsemen. He also had a base in Taxila, after promising to help Taxiles against his enemy, King Porus. Alexander met Porus at the Battle of Hydaspes in 326 BCE, which included war elephants. After the battle, Porus was allowed to continue ruling his kingdom and became an ally of Alexander, and Alexander continued to march further into India.

Mutiny

Following Alexander's victory at the Siege of Sangala, he and his men reached the river Hyphasis, alternatively known as the Beas. According to Arrian:

The country beyond the Hyphasis was said to be prosperous and its inhabitants able farmers and brave fighters. ... These Indians also had many more elephants than any other of their countrymen, and what is more, elephants of surpassing size and courage. These reports stirred Alexander's desire to go farther. But the Macedonians had by now grown quite weary of their king's plans, seeing him charging from labor to labor, danger to danger. (227)

The men reached a consensus; they did not want to follow Alexander further into Indian territory. Diodorus Siculus adds to the feelings of the soldiers:

Alexander observed that his soldiers were exhausted with their constant campaigns. They had spent almost eight years among toils and dangers, and it was necessary to raise their spirits by an effective appeal if they were to undertake the expedition against the Gandaridae. There had been many losses among the soldiers, and no relief from fighting was in sight. The hooves of the horses had been worn thin by steady marching. The arms and armour were wearing out, and Greek clothing was quite gone. They had to clothe themselves in foreign materials, recutting the garments of the Indians. This was the season also, as luck would have it, of the heavy rains. These had been going on for seventy days, to the accompaniment of continuous thunder and lightning. (391)

Alexander gave a speech, summarizing all their exploits throughout the Persian campaign and explained how upon completion of the conquests, their empire would stretch from India to the Pillars of Heracles. A universal empire was just within their grasp. He further added that too many warlike peoples would remain unconquered between the Eastern Sea and the Hyphasis if they turned back. He warned of rebellion and instability within the empire if they were left unchecked. He was hoping to outdo Heracles and Dionysus or achieve glory on par with these mythical figures. Alexander went on to remind his troops that, on equal terms, he fought alongside them and was willing to share the spoils of war with them. If any left now, they would not partake in the wealth.

Upon seeing his officers cheer for Coenus, Alexander threatened to go on and leave those unwilling to venture with him behind. However, he withdrew to his tent for three days and sensed a change of heart within his army. Alexander claimed the omens were unfavorable for further advancement into India and so he ended his march. The army rejoiced at this news. Alexader had them build twelve great altars to the Olympian gods and left King Porus in charge of this easternmost territory.

Discipline in the Macedonian Army

In the Macedonian army, soldiers swore an oath to their king-commanders, but that oath focused on the general allegiance of troops to their respective commanders rather than obedience to certain orders. If oaths were not an important aspect of the army's discipline, training and drill undoubtedly were. Alexander's father, Philip II of Macedon (r. 359-336 BCE) demanded an unprecedented degree of training in the Hellenic world, a policy his son would continue. According to Elizabeth Carney, Philip II had his men “carry a thirty-day ration of flour on their backs, to train by forced marches carrying full rations and equipment. He also forbade wheeled transport and drastically limited the number of support people allotted both infantry and cavalry" (30).

The Opis Mutiny

Another mutiny that took place later in Alexander's career was the Opis Mutiny. At Opis in 324 BCE, Alexander tried to decommission his aging and unfit Macedonian veterans, but the Macedonians did not take kindly to this. According to Arrian, the king's character was adversely affected by the obsequiousness brought upon him by his Asian subjects, and the Macedonians believed they were being replaced by foreign troops. Alexander waded “into the rebellious throng and orders the immediate arrest and execution of thirteen of its leaders” (Arrian, 283). Alexander next gave a speech of how far he and his men progressed together from his father's leadership to a global empire. Three days later he appointed his Persian commanders to high command positions. The Macedonian officers rushed to the palace asking the king to readmit them. Alexander shortly thereafter reconciled with his men and arranged for a banquet to celebrate the harmony between the Macedonians and Asians.

Conclusion

While the reasons for the two mutinies were different, “these two events caused Alexander problems as both king and commander….because they were quarrels that poisoned the relationship between the king/commander and his troops…and thus threatened to compromise future control of the army”(Carney, 42). However, there has been much debate among scholars over whether the Hyphasis incident could truly be considered a mutiny or a revolt. According to Elizabeth Carney, “the concept of mutiny assumes that military discipline is centered on obedience to commands; that is why disobedience to a specific command is seen as so grave an action” (20). Applying this term with its modern associations to the Macedonian and Greek world creates difficulties. Mutiny assumes two things absent in Macedonian military affairs: very consistent and considerable emphasis on absolute obedience to orders, even in peacetime situations, and a clear distinction between the behavior and rights of Macedonian soldiers and subjects. Indeed, none of the primary sources uses a term that translates into “mutiny.”

In his book A King and His Army, Waldemar Heckel also points out that Alexander's skills as a general were lacking at the Hyphasis incident. Furthermore, he claims that Alexander's men were still loyal to their king, their words were not those of mutineers but of men who begged their king to consider their predicament. Nevertheless, the Hyphasis mutiny remains a significant event in Alexander's campaigns as it clearly demonstrated friction between the king and his army. Alexander had lost in a test of wills against his own army at the Hyphasis, and with great reluctance, he put an “eastern terminus” to his campaign of conquest (Arrian, 139). This halted further expansion into India and changed the course of Alexander's campaigns.