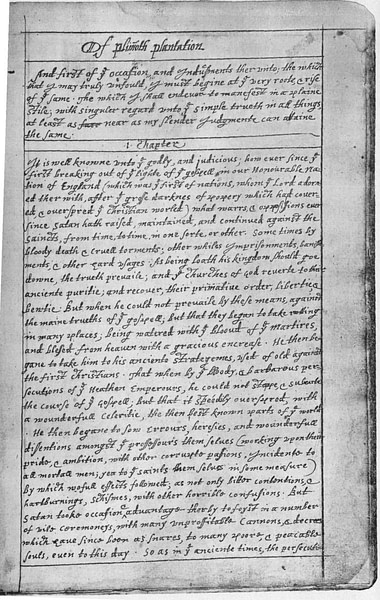

Of Plymouth Plantation (also known as History of the Plymouth Plantation and William Bradford's Journal, written 1630-1651 CE) is the first-hand account of William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE), second governor of the Plymouth Colony (1620-1691 CE) relating the events leading to his congregation of religious separatists (later known as pilgrims) leaving Europe for North America, their voyage aboard the ship Mayflower, and the establishment of the colony in modern-day Massachusetts. Bradford's book is the ultimate source for the term 'pilgrims' as applied to the separatist congregation as he writes of them, "they knew they were pilgrims" in describing their journey of faith to an unknown land (Book I. ch. 7). The work is considered among the most significant of early American literature and history, not only for its artistic and historical value but also its influence on the development of the national character of the United States of America.

Bradford's narrative emphasizes the importance of people of different backgrounds, nationalities, and religious beliefs working together for their collective good but, at the same time, highlights individual accomplishment and how, in a land of unlimited opportunity, one may rise only as high as one's character and determination allow. In concise prose, Bradford narrates the experience of the early colony noting how their commitment to work together with each other and the Native Americans, for the collective good of all, established a community where individual effort was rewarded by benefits, not only for one's self but for all involved.

Although this aspect of the work is far from its focus, the theme of the self-made man creating something from nothing runs throughout and has informed the collective vision of the United States since the book became available to the general public in the 19th century CE. Bradford speaks directly to the reader in an honest voice throughout, emphasizing personal devotion and responsibility to one's God, self, and the greater good, and the determination to succeed in spite of seemingly overwhelming odds.

Persecution & Relocation

Bradford's work begins with the history of the persecution of the religious separatists by the Anglican Church under King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE). Although the church had been founded by Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) during the Protestant Reformation in opposition to the Catholic Church, it still retained many aspects of Catholicism which some Protestants, derisively known by Anglicans as “Puritans” because they wished to purify the Church, objected to.

King James I, the same who commissioned the famous King James Translation of the Bible, was the head of the Anglican Church, interpreted this criticism as treason, and authorized officials to fine, arrest, imprison, and even execute dissenters. By age 12, Bradford had read the Geneva Bible, a translation influenced by the theology of the reformer John Calvin (l. 1509-1564 CE), who advocated strict adherence to a literal interpretation of the scriptures which encouraged worship services modeled on the simplicity of the early Christian community. Bradford was further influenced by a religious movement known as Brownism, founded by a former Anglican priest named Robert Browne (l. 1550-1633 CE) who claimed the Church was too corrupt to be purified and the only course for a true believer was to separate one's self from it. Bradford found like-minded Christians in a separatist congregation in the village of Scrooby, close to his hometown of Austerfield, England.

In 1607 CE, the Anglican Church became aware of the Scrooby congregation and arrested some, placing others under surveillance, and fining those they could. The congregation, under the leadership of John Robinson (l. 1576-1628 CE) sold their belongings and relocated to Leiden, the Netherlands, where the government practiced a policy of religious tolerance.

Between 1607-1618 CE, the congregation lived freely in Leiden but could only hold menial jobs and became concerned that their children were losing their English heritage. The English had established the colony of Jamestown in the Virginia Patent of North America in 1607 CE, which, ten years later, was flourishing, and the Leiden congregation were already looking into some means of creating their own colony in Virginia when, in 1618 CE, one of their leading members, William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE), published a tract criticizing the Anglican Church and orders were given by the English officials for his arrest. Brewster was hidden by his friends, but the congregation stepped up their efforts to relocate and contracted with Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE), who was a merchant adventurer who matched potential colonists with investors. By June of 1620 CE, they had two ships, the Speedwell and the Mayflower, and were ready to begin their voyage across the Atlantic Ocean to a new home.

The Voyage & Compact

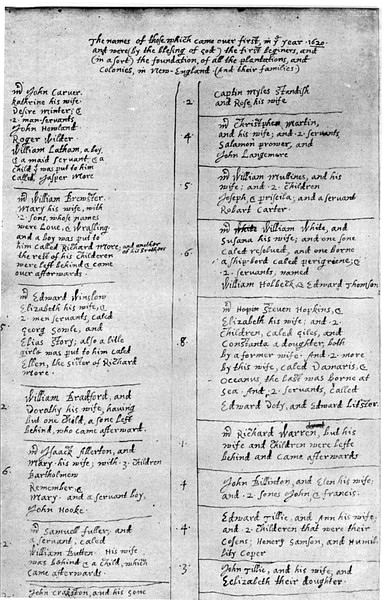

The negotiations between the congregation's representatives, John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) and Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) and Weston did not go smoothly, and Bradford includes letters between them amply illustrating this. A further challenge came when Weston hired some, and invited others, not of the separatists' faith to help them establish the colony in order to turn a profit for the investors and himself. The separatists had been given to understand that they would be traveling as a cohesive group with a single vision, and these new arrivals (whom they referred to as Strangers) were an unwelcome surprise but accepted by them as another trial sent by their God to test their resolve.

Shortly after the ships departed from Southampton, England, the Speedwell was found to be leaking and had to be abandoned, necessitating some 20 passengers to board the already tightly packed Mayflower. Bradford describes the voyage across, during which the passengers lived in near darkness on the 'tween deck between the main and the cargo hold, as difficult to say the least. They began with "fair winds", but the sea grew rough and the winds high, shaking the ship and, at one point, cracking the main beam which threatened to end the voyage midway before it was repaired.

After over two months at sea, they sighted land on 9 November 1620 CE, and their captain, Christopher Jones (l. c. 1570-1622 CE) recognized instantly they were nowhere near their destination of the Virginia Patent. The area of modern-day New England had been mapped by Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) in 1614 CE and was known to Jones and the others, but this was little comfort as it was still a wilderness and, further, outside of the authority of their charter.

They had no legal right to land there and so Jones steered south, thinking to follow the coast down to their original destination, but bad weather, dangerous shoals, and lack of supplies forced him to turn around and head back north to Cape Cod. The separatists had expected to land near enough to established settlements to ask for help if needed; now they found themselves floating off the coast in a strange land with no one to welcome them and no hope of assistance.

Since they were not on English land, some of the Strangers made it clear that, once ashore, it would be every man for himself since there was none among them of any civil authority. Bradford notes how these "discontented and mutinous speeches" led to the composition of the Mayflower Compact, an agreement establishing a democratic form of government for the colony, which all were asked to sign before the anchor was dropped and anyone allowed to leave the ship. 41 of the male passengers signed the compact which gave every man in the colony a voice in deciding law and policy. With the dispute settled, John Carver was then elected governor and began delegating responsibility.

First Winter & Native Americans

Between 11 November and 21 December 1620 CE, the passengers explored the area searching for the best place to establish the settlement and, while they did, people began dying. Bradford's wife Dorothy fell overboard on 7 December 1620 CE and drowned while others died of scurvy, exposure, and other diseases. Earlier English expeditions to the region had spread disease, killing off large numbers of the Native Americans, and others – especially of one Thomas Hunt – had kidnapped a number of natives to be sold into slavery. The Mayflower passengers, therefore, did not receive a warm welcome from the Nauset tribe when they were met on 8 December 1620 CE in what Bradford calls the First Encounter. By March of 1621 CE, 50% of the passengers and crew were dead, and the survivors were left to continue building the settlement, refusing to give up.

They were saved by the Native Americans of the region who taught them how to plant crops, fish, hunt, and survive. Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653 CE) was the first to approach the settlement in March 1621 CE and welcomed them in broken English. He introduced them to Tisquantum (better known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE), one of those who had been kidnapped years earlier, escaped to England, and was fluent in English, who served as interpreter between the settlers and the chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661 CE). John Carver and another of the leading separatists, Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655 CE) negotiated a peace treaty with Massasoit, which was mutually beneficial, and the Plymouth Colony began to flourish.

Thanksgiving & Development

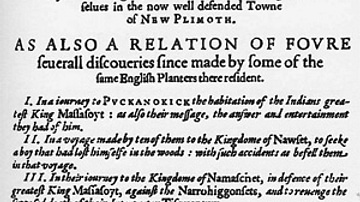

Bradford never refers to the harvest feast of the fall of 1621 CE as Thanksgiving but notes how "all summer there was no want" and they finally had a good provision of food including an "abundance of wild turkey" (58). The story which would form the basis of the First Thanksgiving does not come from Of Plymouth Plantation but from an earlier work by Bradford and Winslow known as Mourt's Relation, written between 1620-1621 CE and published in 1622 CE in London as well as Winslow's Good News from New England (published 1624 CE). Bradford does, however, note the development of good relations between the settlers and the Native Americans and consistently speaks of Massasoit's tribe of the Pokanokets, as well as the others who made up the Wampanoag Confederacy, with respect.

The good relationship between the Plymouth Colony and Massasoit's people would continue, more or less, until the great chief's death, but, long before that, the colonists and Native Americans of different tribes – including some of the Wampanoag – came into conflict as more ships arrived carrying more settlers and the Native Americans lost more and more of their land and resources. The first serious altercation came in 1622 CE when Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE) led a strike against a group of natives who were allegedly planning to attack a nearby settlement. By this time, Carver was dead, and Bradford, as the second governor, approved Standish's mission as preventative, seeming to believe he would use non-lethal force, and later regretted it for having seriously damaged their relationship and trade prospects with the natives.

The arrival of even more colonists from Europe and their poor treatment of the Native Americans would eventually result in King Philips's War (1675-1678 CE), which would influence European-Native American relations for the next three hundred years, but Bradford's narrative ends in 1650 CE with a list of those who arrived on the Mayflower (the "old stock" as he calls them) and what happened to them, noting how in the 30 years since he has been governor, "there have sprung up from that stock over 160 persons now living in this year 1650; and of the old stock itself nearly thirty persons still survive" (226). The work ends with praise for God whom Bradford credits with the colony's success.

History of the Manuscript

Of Plymouth Plantation was composed between 1630-1651 CE while Bradford was governor. The book was never intended for publication but, rather, as a journal to inspire others in the community at Plymouth with a history of its origin and the challenges the first settlers faced and overcame. It was left to his son, Major William Bradford, who passed it to his son, Major John Bradford, and so to his son, Samuel Bradford until, in 1728 CE, it was loaned by the family to the historian Thomas Prince (l. 1687-1758 CE) as a source for his work on the history of New England under the stipulation that he could retain it only as long as he lived; afterwards, it seems, it was to be returned to the Bradford family.

When Prince died in 1758 CE, he left his considerable collection of manuscripts to the New England Library of Prints and Manuscripts, which was housed in the Old South Church of Boston, and Bradford's work went with the rest. Early historians of the English colonies, such as Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts (l. 1711-1780 CE), drew on the manuscript for the second volume of his History of the Province of Massachusetts-Bay in 1767 CE, and as Prince had stipulated that no one could take any manuscript from the library, he must have consulted Bradford's work at the Old South Church.

When the American War for Independence broke out in 1775 CE, the manuscript is assumed to have been still among the others in the church, which was occupied by British troops. Afterwards, it disappeared and, presumably, has been taken by one of the soldiers. This claim is speculative, however, as it could have been taken earlier, even by Hutchinson himself who left the colonies and returned to England. According to scholar Harold Paget:

It is supposed that the manuscript found its way to England sometime between the years 1768 and 1785, being deposited under the title of "The Log of the Mayflower", at Fulham Palace as the Public Registry for Historical and Ecclesiastical Documents relating to the Dioceses of London and to the Colonial and other Possessions of Great Britain beyond the seas – New Plymouth being, ecclesiastically, attached to the Diocese of London. (ix)

In 1844 CE, the English bishop Samuel Wilberforce (l. 1805-1873 CE) published his History of the Protestant Episcopal Church in America, and American historians recognized his use of Bradford's work as a source. One of these, Reverend John Barry, who was acquainted with Bradford's work as cited in Prince's history, was the first to notice the citations in Wilberforce which quoted Bradford word-for-word and referenced a "Manuscript History of the Plantation at Plymouth in the Fulham Library". Barry brought this to the attention of his friend, the historian and editor Charles Deane, who promptly wrote his colleague, Reverend Joseph Hunter, in England, asking him to visit the Fulham Library and try to identify the manuscript. Hunter confirmed that the work Wilberforce had used was Bradford's original manuscript.

Deane requested the manuscript be returned to the United States, but England refused, sending instead a photographic copy, which Deane then typeset, edited, and published in 1856 CE. Bradford's work was an immediate success and encouraged American politicians, scholars, historians, and members of the Bradford family to pressure the government of Great Britain to return the manuscript between 1860-1897 CE. The Massachusetts senator George Frisbie Hoar (l. 1826-1904 CE) stepped up this initiative, enlisting the aid of the American ambassador to Great Britain, Francis Bayard.

Bayard contacted the cleric Frederick Temple (l. 1821-1902 CE) c. 1895 CE, who was then Bishop of London, asking for the manuscript's return. Temple agreed to Bayard's request, personally, but could not officially release the work as its contents related to births and deaths of former members of the Anglican Church of London and was therefore legally the property of the London diocese. Temple told Bayard he would have to consult with the Archbishop of Canterbury but, the next year, was installed as the Archbishop, and Bradford's work was returned to the United States in 1897 CE. An edition was published in 1901 CE, and the authoritative version in 1912 CE, which has never gone out of print. Bradford's original manuscript was deposited with the State Library of Massachusetts in Boston where it remains today.

Conclusion

There are many impressive aspects to Bradford's work - artistically, his choice of detail, narrative form, progression, and honesty of expression, and, historically, its significance in chronicling the early years of the colony and the initial cordial relations between the immigrants and Native Americans – but among the most striking is the depiction of the passengers, whether separatist or Stranger, in facing the unknown. Every passenger who boarded the Mayflower surrendered their former lives in hope of something better and, according to Bradford, did not look back.

Human beings tend to cling to what they know. One's home and traditions are embraced so fiercely because they anchor one to the past and provide a sense of personal and communal identity. Bradford's congregation, and the others who traveled with them, left all of that behind for a vision of a new life in a new world they had no guarantee they would ever even reach and, once arrived, found to be far from anything they had been given to expect. Even so, with only themselves to rely on, they persevered in hope that they would not only survive but triumph over every challenge, and that hope, inspired by their faith, provided them with a new home and traditions which would inform the vision of a whole new nation.