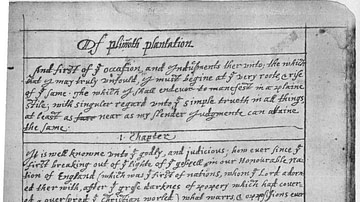

William Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation is the first-hand account of the voyage of the ship Mayflower, founding of Plymouth Colony in modern-day Massachusetts, and the further colonization of the region of the United States now known as New England, written between 1630-1651 CE and covering the period c. 1607-1650 CE. William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) was the second governor of the Plymouth Colony (1620-1691 CE) who arrived in North America aboard the Mayflower and was a central participant in the founding and development of the settlement from the beginning. Of Plymouth Plantation is, therefore, considered one of the most important works from early Colonial America.

Bradford tells his story in elegant, straightforward prose, writing in the third person to lend a sense of objectivity, beginning with the religious intolerance of the Anglican Church under King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE), which drove his congregation of separatists from the village of Scrooby, England, to Leiden, the Netherlands, and finally to North America aboard the Mayflower. The Protestant Reformation which gave birth to the Anglican Church under the reign of King Henry VIII of England (1509-1547 CE) was a reaction against the policies and practices of the Catholic Church and, accordingly, Protestant churches rejected Catholic trappings in worship services, organization, and personal observance. The Anglican Church, however, retained not only the pageantry of a Catholic service but many other aspects of the faith which religious Puritans – those who wanted to purify the Church of all that was not based on scripture – strongly objected to.

One sect of Puritans came to be known as separatists – those who had come to believe the Anglican Church was too corrupt to be redeemed – who chose to organize themselves as independent congregations in order to live their belief that the Bible was the literal word of God and one's life needed to be modeled on the paradigm of the early Christian community as depicted in the New Testament. Since King James I was the head of the Anglican Church, any criticism leveled against it was interpreted as treason, and religious dissent of any kind was not tolerated. Dissenters were fined, arrested, imprisoned, and executed, and it is against this historical background that Bradford begins his story which ends with the colony he helped to establish in the North American wilderness of New England.

Dissent & Self-Exile

Bradford, baptized an Anglican, was orphaned by the age of 12 and went to live and work on his uncle's farm where he soon contracted some unknown illness, which kept him bedridden. He spent his time reading the Geneva Bible, a translation informed by the fundamentalist theology of John Calvin (l. 1509-1564 CE) who believed in the inerrancy of scripture. Along with the Bible, Bradford read classical works and Foxe's Book of Martyrs, all of which led him to conclude that the Anglican Church did not represent the original vision of Jesus Christ and the early Christians. He found a new spiritual home with the congregation of separatists in Scrooby, not far from his hometown of Austerfield.

The separatist congregation was, of course, illegal and had to meet secretly to avoid persecution, and this worked well enough until 1607 CE when they were discovered. Many were arrested, others fined, and they knew they would have to leave if they wanted to continue to live their faith as they felt they must. They decided to leave the only homes they had ever known and relocated to the Netherlands where the government maintained a policy of religious tolerance. Bradford relates the feelings of the congregation in Book I. ch. 2:

For these reformers to be thus constrained to leave their native soil, their lands and livings, and all their friends, was a great sacrifice, and was wondered at by many. But to go into a country unknown to them, where they must learn a new language, and get their livings they knew not how, seemed an almost desperate adventure, and a misery worse than death. Further, they were unacquainted with trade, which was the chief industry of their adopted country, having been used only to a plain country life and the innocent pursuit of farming. But these things did not dismay them, though they sometimes troubled them; for their desires were set on the ways of God, to enjoy His ordinances; they rested on His providence and knew Whom they had believed.

They quickly found it was as difficult and dangerous to leave England as it was to stay. They first booked passage with an English captain who turned out to be a staunch Anglican and betrayed them to authorities, resulting in the arrest and imprisonment of a number of them. On their second attempt, they contracted with a Dutch captain who had only loaded half the passengers aboard when an Anglican militia arrived, and he cast off quickly to avoid arrest, leaving the women and children of the congregation behind who had to be sent for later.

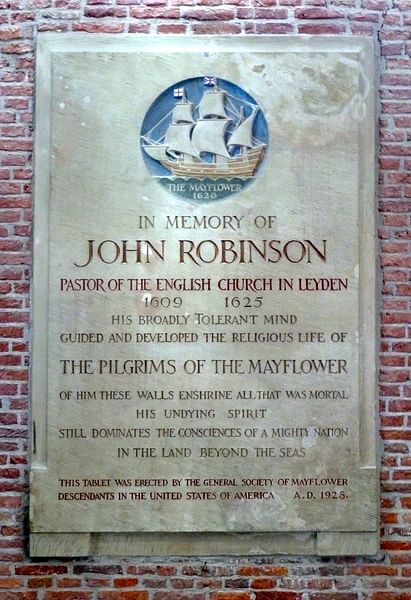

A number of the leading men of the congregation also stayed behind to assist the women and children, among them the pastor John Robinson (l. 1576-1625 CE) and William Brewster (l. 1568-1644 CE). Arriving in Amsterdam, they found a number of other separatist congregations already established, but these were caught up in various doctrinal arguments with each other as well as differing Protestant sects and, to avoid the kind of trouble they had just fled, they moved to Leiden where they remained for the next 12 years.

Flight to the New World

The best jobs in the Netherlands were controlled by guilds, and as foreigners, none of the English of the congregation were eligible to join and were reduced to menial labor. As time went on, though they found they could worship freely, their children began assimilating into Dutch culture, and the congregation feared that they would lose their English heritage. England had established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia in North America in 1607 CE, which, though it struggled at first, was thriving by 1617 CE. The separatists, already living in exile, began researching how they might make their own way across the Atlantic Ocean to the New World but, lacking funds, were taking their time until, in 1618 CE, William Brewster published a tract criticizing the Anglican Church which received considerable attention and orders were issued for his arrest.

Brewster was hidden by the congregation, but they knew they needed to move quickly before he and others were taken. Two members of the congregation – John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE) and Robert Cushman (l. 1577-1625 CE) entered into negotiations with a banker named Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647 CE), a merchant adventurer who paired prospective colonists to the New World with investors. The negotiations did not always go smoothly and Bradford includes letters between Weston, Carver, and Cushman which make this clear, but finally, two ships were put at their disposal – the passenger ship Speedwell and the cargo carrack Mayflower – and a patent procured which allowed them to legally settle in North America in the region of the Virginia Patent. Although they had no desire to commune too closely with the Anglicans of Jamestown, they were legally bound by contract to the area north of that colony and, further, understood it would be best to have others nearby in case they should require assistance.

Weston had already thought of this, of course, as his main interest was in turning a profit from the colony and so he hired some, and invited others, to go along on the expedition, who were not of the separatists' faith, to help them succeed. These people were known by the congregation as Strangers, and their inclusion caused some of the problems between Weston, Carver, and Cushman, but there was nothing the separatists could do about the situation but comply. The Speedwell was found to be unseaworthy and was abandoned, and 102 passengers were crowded into the 'tween deck of the Mayflower, between the main and the cargo hold, for the trip across the Atlantic. The problems with the Speedwell delayed their departure until September of 1620 CE, and by this time, the seas were rough, although they began with a good start. Bradford describes part of the journey in Book I. ch. 9:

After they had enjoyed fair winds and weather for some time, they encountered cross winds and many fierce storms by which the ship was much shaken, and her upper works made very leaky. One of the main beams amid-ships was bent and cracked which made them afraid that she might not be able to complete the voyage. So some of the chief of the voyagers, seeing that the sailors doubted the efficiency of the ship, entered into serious consultation with the captain and officers, to weigh the danger betimes and rather to return than to cast themselves into desperate and inevitable peril…But at length all opinions, the captain's and others' included, agreed that the ship was sound under the water-line and, as for the buckling of the main beam, there was a great iron screw the passengers had brought out of Holland, by which the beam could be raised into its place; and the carpenter affirmed that with a post put under it, set firm in the lower deck, and otherwise fastened, he could make it hold…So they committed themselves to the will of God and resolved to proceed.

Arrival in North America

Only two people died on the crossing, a crew member and a servant, but almost all suffered from seasickness and were forced to live in the half-light of the 'tween deck, with little fresh air or too much, without privacy or latrines, for a little over two months. When they finally saw land on 9 November 1620 CE, they found they had been blown far off course and were in the region mapped years before known as New England, some 500 miles north of where they should have landed. Christopher Jones, Captain of the Mayflower (l. c. 1570-1622 CE) tried to navigate down the coast toward the Virginia Patent, but bad weather, rough shoals, and meager supplies forced him to turn around; the passengers would have to establish their colony in the wilderness they saw before them. Bradford comments on the moment:

But here I cannot but make a pause, and stand half amazed at this poor people's present condition; and so I think will the reader, too, when he considers it well. Having thus passed the vast ocean, and that sea of troubles before while they were making their preparations, they now had no friends to welcome them, nor inns to entertain and refresh their weather-beaten bodies, nor houses – much less towns – to repair to. (Book I. ch. 9)

Their prospects of success seemed bleak to them. Captain Jones had only been commissioned to bring them to North America, not help them establish the colony. He had been instructed to remain only until a fit place for settlement had been selected, and then he was to return to England, and the passengers would be left to fend for themselves. Bradford writes:

If they looked behind them, there was the mighty ocean which they had passed, and was now a gulf separating them from all civilized parts of the world. If it be said that they had their ship to turn to, it is true; but what did they hear daily from the captain and crew? That they should quickly look out for a place with their shallop, where they would be not far off; for the season was such that the captain would not approach nearer to the shore till a harbor had been discovered which he could enter safely; and that the food was being consumed apace, but he must and would keep sufficient for the return voyage. It was even muttered by some of the crew that if they did not find a place in time, they would turn them and their goods ashore and leave them. (Book I. ch. 9)

Their situation worsened when some of the Strangers among them pointed out that, since they would not be settling in the Virginia Patent, under English law, there was nothing to constrain them and they would live as they wished once they had landed. Bradford and some of the others understood that this would mean the death of the colony before it had even begun since it was clear that everyone would have to work together toward a common goal just to survive. Bradford describes the composition and signing of the document known as the Mayflower Compact which would establish the government and laws of the new colony:

[The signing of the compact] was occasioned partly by the discontented and mutinous speeches that some of the strangers amongst them had let fall: that when they got ashore they would use their liberty that none had power to command them, the patent procured being for Virginia, and not for New England, which belonged to another company, with which the Virginia company had nothing to do. And, further, it was believed by the leading men among the settlers that such a deed, drawn up by themselves, considering their present condition, would be as effective as any patent, and in some respects more so. (Book II. ch. 1)

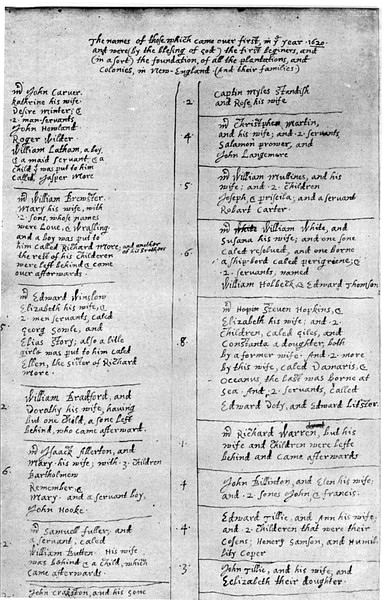

41 of the men present signed the compact agreeing to abide by it; those who did not sign were mainly servants who had no choice but to obey their masters anyway. Once the compact was signed, John Carver was elected the first governor, and the Mayflower dropped anchor on 11 November 1620 CE.

First Winter & Survival

Between 11 November and 21 December 1620 CE, the passengers, often assisted by the crew, explored the area in search of a place to build their settlement. Bradford's wife Dorothy drowned after falling overboard while he was away on one of the exploratory missions, and many others died after her of exposure, scurvy, malnutrition, and other ailments; by March 1621 CE, 50% of the passengers and crew were dead.

Throughout the winter, Bradford writes, almost everyone was sick, himself included, and were tended constantly by those who remained healthy, no more than seven. Work on the settlement had therefore not progressed very far and, with spring approaching, and the remaining crew of the Mayflower recovering, Jones would be returning to England. No crops had been planted, the passengers had no skill at fishing, and most of the meat of the past few months had come from hunting expeditions led by Jones or members of his crew. The ship's stores had already been low when the Mayflower first approached the coast, and now the colonists were facing almost certain death unless they could work out how to live off the land.

On 8 December 1620 CE, on one of their exploratory expeditions, they had been attacked by Native Americans (whom they later learned were of the Nauset tribe), an event Bradford defines as the First Encounter, and they felt they could expect no help from the people already living there. It was due to the natives, however, that the colony would survive. In March of 1621 CE, a Native American named Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653 CE) walked boldly into the half-built village and addressed them in broken English. He later brought another, Tisquantum (better known as Squanto, l. c. 1585-1622 CE), who had been kidnapped by the English years before to be sold as a slave and knew their language. Squanto would not only act as interpreter between the colonists and Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661 CE), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy of the region, but teach them how to plant crops and survive in their new environment.

Conclusion

Bradford's narrative continues from this point to relate the story of the Plymouth Colony's mutually beneficial relationship with the Native Americans founded on the peace treaty forged between them and the prosperous trade which this enabled. Jones left on the Mayflower in April of 1621 CE, but now the colonists felt more secure in their new home as they were able to count on the assistance and protection of their Native American neighbors.

The success of the colony, however, brought more ships and more colonists, and these, increasingly, did not share the kind of respect for the Native Americans that the passengers of the Mayflower had shown. The treaty agreed to between John Carver and Massasoit would continue to be honored until the great chief's death by the Plymouth Colony, but the same cannot be said for other settlements which began to spring up, requiring more and more land at the expense of the natives.

Bradford never shies away from unpleasant moments or conflicts between the immigrants and the natives, nor between the colonists and each other, delivering, as he says, "an accurate account of the project…at least, as near as my slender judgment can attain to it" (Book I. ch. 1). He never excuses himself or others for lapses in that judgment but presents the story of the early days of the colony honestly; depicting a time when the new arrivals and the long-established natives lived together in peace before the New World was taken and transformed into an image the passengers of the Mayflower had left behind.