Boxing is one of the oldest sports in the world that is still practiced today. Included in the original athletic contests of the Olympic Games, pugilism or boxing was well known and loved by the ancient Greeks and Romans. The style used in the Roman Empire was heavily influenced by their predecessors, the Greeks, and Etruscans. Neither was the first to box, however, as evidence exists from 3rd- millennium BCE Mesopotamia. Historians use ancient literature, sculpture, mosaic, and even new archeological evidence, to piece together how the game may have been played. Boxers would dress in gloves with a variety of styles, square up against their opponent in outdoor fields, make use of quick footwork, feints, guards, cuts, and throws until one of the athletes tapped out or was knocked out. Injuries could be debilitating or fatal but that did not stop the Roman public from celebrating the game to the point of political criticism.

Origins

The earliest depictions of boxing as a formal sport can be traced back to Mesopotamia with discoveries dating as early as the 3rd millennium BCE. A terracotta relief depicting two men squaring off, their wrists wrapped and hands in fists, ready to strike, was found in Eshnunna, dated to c. 2000 BCE. Another relief with similar imagery was dated to c. 1200 BCE in modern-day Tell as-Senkereh, Iraq. The Epic of Gilgamesh makes a mention of pugilism where Gilgamesh battles a rival: "They seized each other, they bent down like expert[s], they destroyed the doorpost, the wall shook" (Kyle, 24). This description lines up well with the form depicted on Mesopotamian reliefs and confirms not only what proper stance may have looked like but also that a stance existed at all. In order to be an expert, a refined skill must exist. Such skills were also practiced in neighboring Assyria, where a "contest in wrestling and athletics" was mentioned in a c. 2000 BCE Assyrian astrological text from Assur. At this point in history, it is clear that combat had risen into the ranks of a dignified sport. However, a distinction between boxing and wrestling is not readily apparent and the largest indication we possess about the form is merely bending down.

For the next thousand years, similar imagery made its way into Minoan art, appears in Hittite depictions, Egyptian art, Greek sculpture and painting, and Etruscan art. As in the case of most Roman customs, the Etruscan and Greek adaptations of the sport would ultimately be the version practiced in the Roman Empire. Despite the stylistic differences between the Greeks and Romans, boxing in the ancient world is commonly considered a uniform sport. Evidence shows that Romans were using similar rules, form, equipment, and technique to that of Classical Greece. However, to accept undocumented details as inherently shared between Greece and Rome is dangerous.

Equipment

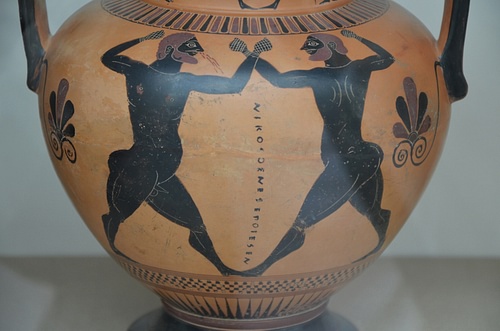

In Ancient Greece, there were three different types of boxing glove. The first type was hardly a glove at all as the Greeks considered thick padding unfit for a real athlete. This style was considered more of a training glove as they provided too much comfort to the wearer. The two styles used by professionals were called light thongs and sharp thongs. Light thongs were thin, flexible, rawhide straps dressed with fat, and wrapped around the hand in various patterns. These were similar to the wraps boxers use today. They show up on Greek pottery from the 4th and 5th centuries BCE and also appear in the Iliad. The lack of enforcement around the knuckles show they were intended to alleviate the strain on the hand muscles rather than act as offense.

The sharp thong was an offensive weapon. Made from a much denser and thicker leather with a heavy casing around the knuckles, these were intended to deal serious damage to the opponent. Rather than straps wrapped around the hand, these were structured gloves with finger holes and sheepskin further up the forearm, popular in Greece from the 4th century BCE to the 2nd century CE. The most famous example of the Greek sharp thong is displayed in the Hellenistic statue named The Boxer or The Boxer at Rest. Excavated near the Baths of Constantine, on the south slope of the Quirinal Hill in Rome, historians guess this 1st-century BCE bronze beauty was displayed in the Roman baths. The Boxer of the Quirinal is not alone in the Roman world; the Greek sharp thong can be also found on Roman vases and mosaics, such as the floor found in Villelaure, France dated to 175 CE. The Romans did not adopt any of the Greek styles but this one, and the reason was obvious; they found the others too soft. 3rd-century CE Roman emperor, Gallienus (r. 253-268 CE), is said to have claimed that the "real" sport was "a much tougher affair" (Poliakoff, 73).

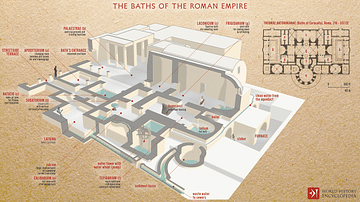

The Roman caestus has become famous for its level of savagery against its enemies. While adopting the construction of the Greek sharp thong, the caestus replaced the heavy, leather knuckle casing with metal. Virgil (70-19 BCE) describes them as follows: "so vast were the seven huge oxhides, all stiff with insewn lead and iron" (Aeneid, 5.404-05). These deadly gloves required sheepskin reinforcement that wrapped all the way up the shoulder and they show up on several bronze figurines from the 1st century CE. There are even depictions of caesti in which the metal knuckles included protruding spikes or blades; one example can be seen in a Roman mosaic of athletes from the Baths of Caracalla dated to the 3rd century CE. These gloves were popular for their merciless brutality in gladiator games. The popularity of the light thong, sharp thong, and caestus can be used somewhat as a timeline. They signify three eras of ancient boxing, since they went in and out of fashion in that order.

A recent archeological find has put ancient boxing in the spotlight once more as a topic of research. In February 2018 CE, two leather hand wrappings were found in Hexham, Northumberland, near Hadrian's Wall. After being identified as ancient boxing gloves from c. 120 CE, they garnered attention from historians and enthusiasts worldwide. These became the only known pair of gloves from the Roman Empire preserved in such a condition to date. They fit over a modern human hand, complete with impressions of the knuckles still left on the inside, a chilling reminder of how closely they connect us with the past. Prior to this discovery, historians had to rely solely on artistic depictions.

Rules & Technique

One major factor to the beginning of every ancient boxing game was finding a favorable position on the field. The athletes competed outside in the summer and so the sun in their eyes was a major obstacle to be avoided. Greek poet Theocritus described a typical beginning to a match in his Idylls:

Now was there much ado which should have the sunshine at his back; but he cunning of my Polydeuces outwent the mighty man, and those beams did fall full in Amycus his face. (Idylls, 22.83-86)

Boxing matches standardly took place in open-air courtyards. It was considered among the indoor athletics, however, since it could be held in the designated halls of large bathhouses as well. The match would have included a lot of quick footwork, small steps, feints, and shifting between the knees, not unlike the modern day. The 1st-century CE philosopher Philo of Alexandria describes a proficient boxer as the following:

[He] pushes away the punches coming at him with both hands and bends his neck this way and that, guarding against being struck. Often he stands on tiptoe and draw himself up to his full height, then drawing himself back he forces his opponent to throw idle punches as if he were shadow boxing. (Philo of Alexandria, On the Creation, 80-81.)

To get an even clearer picture, E. Norman Gardiner in Athletics of the Ancient World describes the perfect stance as "body upright, head erect, and left foot advanced" with the leg "slightly bent, the foot pointing forward while the right foot is sometimes at right angles to it" (204). Like Philo's passage, the footwork sounds about the same as today. The open position of the body, however, could not succeed in modern boxing. Included in the ancient technique was extending the left arm straight forward as a guard while the back arm was used for hooks and upper cuts. This opened the body significantly sideways. This stance was successful in antiquity because of the lack of body blows. The outstretched left arm and offensive right arm can be found on a multitude of Greek vases around the 4th and 5th centuries BCE. All of them depict the cuts and throws landing on the head. The picture we receive, therefore, is that body blows were far less common in the ancient world. Instead, their head blows included even more cuts that are considered illegal in modern boxing.

A popular one of these now-illegal head blows from the ancient world was thrown from above. Vergil described it in the Aeneid as the following, "Then Entellus, rising, put forth his right [fist], lifted high; the other speedily foresaw the down-coming blow," and the opponent dodged (Aeneid, 5.443-48). The head blow returns in the 2nd century CE in the form of a Roman clay lamp. It depicts one arm outstretched, the other thrown from above, as well as the proper lunging stance to give himself the most power.

An ancient boxing match ended when one of the opponents tapped out or was knocked out. Tapping out was indicated by holding up a hand. This often included a single, index finger. The games did not have rounds. Competitors would continue until its end. One strong example of a match ending by knock out can be found in the Iliad when Epeus takes down Euryalus with a "smashing roundhouse hook to the head—a knockout blow!" (Iliad, 23.768). Conversely, the tap out can be found on Greek vases from the Classical period. There are multiple examples of a man raising his index finger while down, signifying his surrender. The assumption that this practice was still in use in Imperial Rome may need looking into, however, seeing as no surviving evidence for the index finger tap out remains from the Roman Empire.

Some rules and techniques in ancient boxing are still up for debate among Classical scholars. Some assert there was no form of boxing ring ever present. Others include examples of vases that show barriers such as ladders working to confine the competitors' distance. An Italic vase from the 6th century BCE depicts this style of barrier. Considering how rarely boxing rings were depicted even back then, it cannot be relied upon as standard practice by the time of the Roman Empire.

Boxing, wrestling, and most other combat sports are meticulously divided by weight class in modern competition. It appears this practice was virtually unknown to the ancient world, seeing as big and small men appear fighting each other in literature and artwork quite often. Epeus from the Iliad was far larger than Euryalus. Theocritus, too, said Polydeuces was far larger than Amytus. In both examples, the average-sounding man wins. References like these reveal that the ancients did not find a use for dividing competitors by weight. Superior technique could lead them to triumph against their odds. This practice was adopted in the gladiator games as well. Unfortunately, instances retained from the real battles were often less favorable to small boxers than literature or poetry would indicate. In his book Sports Spectators, Allen Guttmann mentions the mixed styles of gladiatorial combat in which the larger boxers tended to demolish their lighter and smaller opponents.

Traumatic Results

Violence was no small feature in the ancient boxing canon. There is no doubt that the level of injury involved could be serious. Bruising of the limbs or face, edemas and hematomas, which are the leaking or clotting of blood flow in the body's tissue, cauliflower ear, which is a reaction to frequent percussion damage to the ear perichondrium, fractures, especially in the nose that could lead to a loss of smell, cranium-brain bruising, which could result in severe disability from cerebral hemorrhage, loss of teeth, and even death could make up the list of effects an ancient boxer might face. Many of these effects became lifelong deformities that could not be cured by the medical technology of the ancient world. Greek physician Galen, living in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, recognized a few. He stated that as athletes grow old, they do the following.

creep, wrinkle and squint due to the severe blows; their eyes are filled with catarrhal liquids, their teeth fall, and their bones become porotic and break easily. [Galen, The Art of Medicine, 11.]

Injuries are not excluded from combat in artwork. Many Greek vases show boxers bleeding from the nose while facing an opponent. Through various Etruscan funerary wall paintings such as the Tomb of the Augurs from Tarquinia c. 540-530 BCE and the Tomb of the Monkey at Chiusi c. 480 BCE, it is possible to reconstruct an even bloodier form of fighting sports than that seen in the Greek world. The Tomb of Augurs shows men squaring up like those found in Mesopotamia, but also a unique scene labeled the "Phersu game." It displays a man bound in string, wearing nothing but a loincloth and another cloth over his face. He is bitten by a dog and bleeding from six areas. Etruscans enjoyed a certain degree of violence in their entertainments the Greeks would have found appalling. Etruscan sport was more focused on the spectacle than the talent of the athletes, which differs strongly from the Greek approach. For example, genitalia were not off-limits to the Etruscans. Etruscan practice laid down the foundation for more Roman sports that would develop from boxing and wrestling, such as beast hunting and gladiator games. Boxing is only one example of the many ways in which Rome inherited an Etruscan ferocity that differed from the Greeks.

Conclusion

Tomb paintings, vases, friezes, and bronze statues, as well as literature by Homer, Virgil, Theocritus, Philo, and Galen, provide a modern enthusiast with a wonderfully clear image of what boxing may have looked like in Imperial Rome. It is also clear that there were mixed opinions about pugilism. A fear persisted that young boys would prefer fighting for sport over fighting in the Roman army. Tacitus (c. 56 - c. 118 CE) believed that Roman warfare should be the sole priority among future generations; he did not want recreational training to overshadow military training. On the other hand, Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) is known to have been a lover of boxing. Suetonius (c. 69 - c. 130/140 CE) wrote that he loved to watch athletes compete, Roman or Greek. The preference for boxing in Rome over other athletics was likely inherited from the Etruscans. Polarly opposite to Greek mentality, the more boxing was considered a refined, formal, Olympic-style competition with rules, the more skeptical many Romans became of it.