The story of the pilgrims of Plymouth Colony is well known regarding the basic facts: they sailed on the Mayflower, arrived off the coast of Massachusetts on 11 November 1620, came ashore at Plymouth Rock, half of them died the first winter, and the survivors established the first successful colony in New England.

Their harvest observance in 1621 later became celebrated as the First Thanksgiving, shared with their Native American neighbors who had helped them survive, their success encouraged further colonization and, within ten years of their arrival, English colonies proliferated along the east coast of North America in what would become the United States.

The pilgrims' story had already become a foundational myth of the United States by the 19th century when President Abraham Lincoln (served 1861-1865) decreed the 4th Thursday of November the national holiday of Thanksgiving, and since then, the above story is repeated with little change. The pilgrims were human beings, however, not characters, and their story has much greater depth than the glossed version presented annually in November in the United States through pageants, readings, and other observances. The following are ten pilgrim facts frequently overlooked, misrepresented, or ignored.

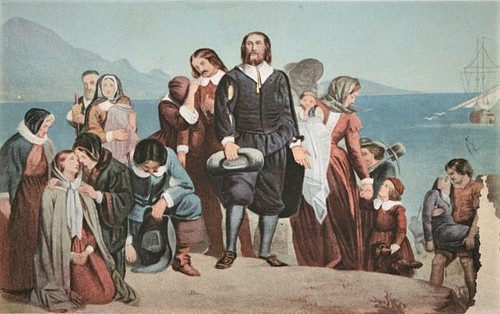

Wore Bright Clothing

The pilgrims did not restrict themselves to all-black attire and, actually, wore brightly colored clothing most of the time. Their black outfits were worn on the sabbath and on occasions known as Days of Humiliation when they would repent of their sins and ask forgiveness. In their daily lives, their wardrobes were fairly extensive, and various articles were of many different colors. This has been established through the inventories of personal possessions written up for probate after a death. Although Pilgrim Fathers such as William Bradford (l. 1590-1657), William Brewster (l. 1568-1644) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) are routinely depicted in their dark pilgrim garb, their inventories show a much brighter side.

Bradford was fond of a scarlet waistcoat and violet cloak, Brewster favored different colored caps, a violet coat, and green underwear, and Winslow, like many of the others, wore russet garments (a vest or cloak) over a white linen shirt. Contrary to the traditional images, the pilgrims did not wear tall, black hats with buckles on them, nor did they have buckles on their shoes; this image is a 19th-century construct. Buckles were unavailable to the common people of England c. 1620, and even if they had been, the pilgrims frowned on ornamentation of any kind.

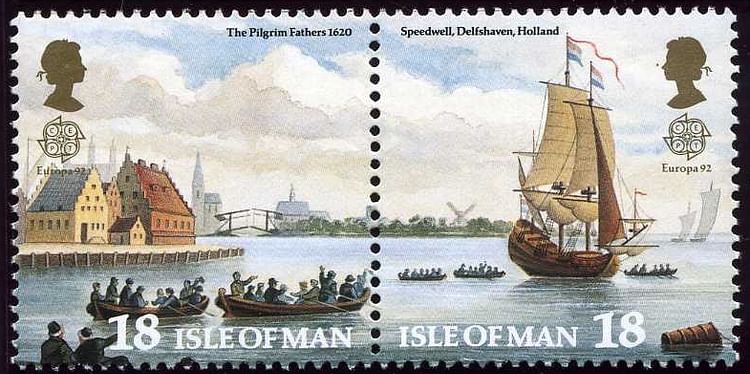

Mayflower Was One of Two Ships

Although the name of the Mayflower is well-known as the pilgrims' famous ship, it was never intended to carry them all to North America. The people who became known as the pilgrims were Puritan separatists who had relocated from England to Leiden, the Netherlands, escaping the persecution of James I of England (r. 1603-1625) and his Anglican Church which did not tolerate religious dissent. After 12 years in the Netherlands, they had to relocate again and purchased a passenger ship known as the Speedwell to take them across the Atlantic. The Mayflower, rented for them by the merchant adventurer Thomas Weston (l. 1584 - c. 1647) who arranged financing for the expedition, was only intended to serve as their cargo ship and carry any overflow of passengers.

Once the group embarked in July 1620, however, the Speedwell leaked, and they had to return to land twice for repairs, finally abandoning the ship, and a number of passengers then boarded the Mayflower while others remained behind. It was later discovered, according to Bradford, that the captain of the Speedwell had overmasted the ship on purpose in order to make it leak so he could get out of his contract which called for him and his crew to remain in North America for a year so the Speedwell could serve the colonists' needs. Once the Mayflower sailed off, the Speedwell's masts were trimmed, and it continued in service until 1635 without a problem.

Not All Mayflower Passengers Were Pilgrims

Initially, the separatist congregation of Leiden contracted with Weston to transport only themselves to the New World. Weston was not interested in their religious convictions or plans to establish their own community, however, as his chief responsibility was returning a profit to investors. He, therefore, hired or invited a number of others to join the expedition who were Anglicans and whom the separatists referred to as Strangers (those not of their faith), including some of the best-known members of the Plymouth Colony such as Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644) and Richard Warren (l. c. 1578-1628). Other well-known Strangers were Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656) and John Alden (l. c. 1598-1687), but Weston had nothing to do with these two. Standish was a friend of the congregation who was personally invited, while Alden was a cooper and carpenter who served as a member of the crew.

They Were Supposed to Land in Virginia

The Mayflower was supposed to cross the Atlantic during mid-summer on a direct route to the Virginia Patent where the English had established the Jamestown Colony of Virginia in 1607. Although Jamestown struggled at first, by 1620, it was thriving due to its lucrative tobacco crop, and the Leiden congregation had planned to settle to the north, far enough so they would not be bothered by those who did not share their faith but close enough to enable them to ask for help.

Due to the troubles with the Speedwell, the Mayflower did not leave England until 6 September 1620 when the seas were rougher, and the ship was blown off course, finally sighting land on 9 November 1620 and recognizing it as Massachusetts. Christopher Jones, Captain of the Mayflower (l. c. 1570-1622), tried to make a run down the coast to Virginia, but lack of supplies, bad weather, and dangerous shoals prevented this, requiring him to turn about and settle the passengers in Massachusetts. If it were not for the scheme of the Speedwell's captain, the expedition would have sailed in July, probably landed in Virginia, and the history of the colonization of New England would be quite different.

Mayflower Compact Influence

The Mayflower passengers' patent was only valid in Virginia, and once it was determined that they would have to settle in Massachusetts, some of the Strangers pointed out that now they would live as they pleased since the patent – and so English law – had no authority in their new home. Members of the Leiden congregation objected to this, recognizing that they would all have to work together to survive, much less turn a profit and so some of them, most likely led by the future first governor John Carver (l. 1584-1621), composed the Mayflower Compact, a legal document establishing a democratic form of government which gave every man over the age of 21 a vote in the laws of the colony.

This agreement was signed by 41 of the men on board the Mayflower and would serve as the political and legal basis for the colony until 1691 when Plymouth was absorbed by the larger Massachusetts Bay Company. The document would have far-reaching influence, however, first in the creation of the Articles of Confederation of New England in 1643 and then inspiring state constitutions, the Declaration of Independence, and the United States Constitution.

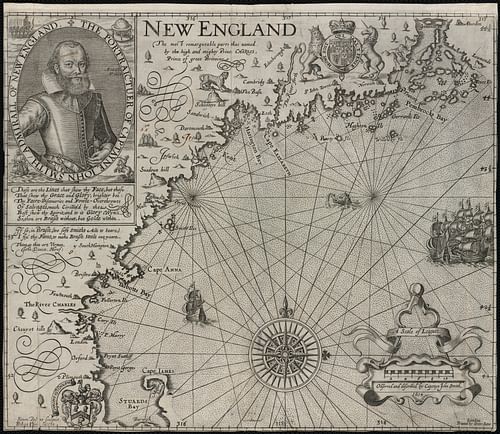

Rejection of John Smith

The stories of Plymouth Colony and Jamestown are often told as though the one had nothing to do with the other, but actually, the tales are entwined. When the pilgrims were researching and organizing their expedition, they initially approached Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631) to be their guide. Smith was one of the original colonists of Jamestown and its leader until he was injured in a gunpowder explosion in 1609 and returned to England. After he recovered, he sailed back to the New World in 1614 and mapped New England, even naming the place (or asking King James I to name it) where the pilgrims would finally settle.

After conferring with Smith, however, the pilgrims felt he was too expensive and his character was too strong and he might come to dominate the group. Smith would later criticize them as stubborn fanatics who could learn nothing “till they be beaten with their own rod” (Philbrick, 60) He had a point in that, had they at least made use of his maps, they would have seen he designated the site of modern-day Boston as the best for a settlement but, instead, they spent over a month – 11 November - 21 December 1620 – searching the coastline for a suitable place to establish themselves, finally deciding on Plymouth. After they rejected Smith, the pilgrims then invited Myles Standish to be their military consultant and guide, though Standish had never been to North America. The only passenger aboard the Mayflower who had any experience in the New World was Stephen Hopkins.

Stephen Hopkins & Shakespeare

Stephen Hopkins left England aboard the ship the Sea Venture to supply Jamestown in 1609 as assistant to the Anglican priest Richard Buck who was being sent as chaplain. The Sea Venture also carried the new governor, Sir Thomas Gates (l. c. 1485-1622), was commanded by Sir George Somers (l. c. 1554-1610), and was wrecked in a storm off the coast of Bermuda. Bermuda had been discovered by the Spanish explorer Juan de Bermudez (d. 1570) in 1505 but was never colonized because of strange sounds and odd sights reported by the crew (most likely tropical birds) interpreted as demons and witches and the islands were known as the Isle of Devils.

The writer William Strachey (l. 1572-1621), who was also on board the Sea Venture, wrote an account of the wreck and their time marooned on Bermuda which included details of Hopkins' troubles with Gates when Hopkins suggested that their patent held no authority here and people could live as they wished. Hopkins, in fact, was almost hanged for treason by Gates until Somers, Strachey, and others intervened. Strachey's account would later inform William Shakespeare's play The Tempest and Hopkins would inspire the character of Stefano. After months on Bermuda, the passengers and crew departed in two ships they had built and reached Jamestown in May of 1610. Hopkins left for England in 1614 when he received word his first wife had died, and his experiences would later serve the Plymouth Colony well.

King James I & the Bible

The King James I referenced in the pilgrims' story as their persecutor is the same monarch who decreed a new translation of the Bible – the King James Translation – one of the most often-cited versions of the work due to the beauty of its language and phrasing. The Anglican Church was established by King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547) who broke with the Catholic Church and authorized the translation known as The Great Bible in 1538, but this work was never as popular as the Geneva Bible (first published in England in 1576) which was heavily influenced by the theology of John Calvin (l. c. 1509-1564) who directly influenced the vision of the Puritans.

The Leiden congregation used the Geneva Bible in their services and so did other religious dissenters. In an effort to create a more popular version of the Bible which would be aligned with Anglican beliefs and practices, James I ordered the creation of his own version of the work to be completed by 47 scholars, overseen by the Archbishop of Canterbury Richard Bancroft (l. 1544-1610), and the work was first published in 1611. James I's persecution of religious dissenters and the creation of the King James Bible both arose from James I's need to impose control over the spiritual lives of his subjects as he equated the power of the Church with his hold on the throne.

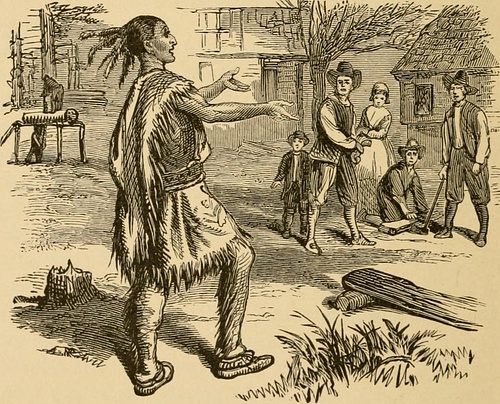

Samoset & Squanto

Samoset (also given as Somerset, l. c. 1590-1653) and Squanto (also known as Tisquantum, l. c. 1585-1622) are the two well-known Native Americans who are regularly featured in the story of the First Thanksgiving. They were not members of the Pokanoket tribe which formed the greater part of the Wampanoag Confederacy governed by Ousamequin (better known by his title, Massasoit, l. c. 1581-1661) who would be so instrumental in helping the Plymouth Colony. According to the neighboring colonist Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647), Samoset was a prisoner of Massasoit who was offered his freedom in return for acting as envoy to the Plymouth Colony. On 16 March 1621, Samoset walked into the settlement, greeting the colonists in English, and later introduced them to Squanto and Massasoit.

Squanto had been kidnapped in 1614 by Thomas Hunt, an associate of John Smith's, to be sold into slavery in Spain. He made his way to England and then back to North America in the company of Captain Thomas Dermer. Squanto found his entire village had died of the plague, and Dermer was attacked and driven off by the Native Americans and so Massasoit took Squanto in. He may have been a prisoner as well and served the chief primarily as interpreter with the English. Between 1621-1622, Squanto secretly tried to undermine Massasoit's authority with the Wampanoag Confederacy, playing the colonists, tribal clans, and Massasoit against each other. He died, possibly poisoned by agents of Massasoit, in 1622. Samoset disappears from the narrative after fulfilling his role as envoy.

Massasoit & the Peace Treaty

Massasoit and then-governor John Carver signed a peace treaty on 22 March 1621 which, though strained at times, would be honored by both parties until after Massasoit's death in 1661. It is sometimes claimed that the pilgrims took advantage of the Wampanoag Confederacy, but Massasoit initiated contact because his population had been so greatly reduced by disease that he had fallen in status and power and had to pay tribute to the neighboring Narragansett tribe while, previously, they had owed it to him. By allying himself with the English, he hoped to regain his former stature – as he did – and the treaty was a means to that end.

First Thanksgiving

The account of the First Thanksgiving is given in the work known as Mourt's Relation (published 1622, republished 1841) by Bradford and Winslow, an account of the first year of the colony, and in Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation (published 1856). The passage from Mourt's Relation is more detailed and reads:

Our harvest being gotten in, our governor sent four men on fowling, that so we might after a special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors. They four in one day killed as much fowl as, with a little help beside, served the company almost a week. At which time, amongst other recreations, we exercised our arms, many of the Indians coming amongst us, and among the rest their greatest king, Massasoit, with some ninety men, whom for three days we entertained and feasted, and they went out and killed five deer, which they brought to the plantation and bestowed on our governor, and upon the captain [Myles Standish] and others. (82)

There is no mention here, nor in Bradford's Of Plymouth Plantation, of the Wampanoag being invited to the celebration. Most likely, Massasoit and his warriors were already nearby on another mission when they heard the discharge of the muskets and came, in accordance with the treaty, to see if the colonists needed help. The First Thanksgiving meal was most likely wild fowl (including turkey, as Bradford mentions them in Of Plymouth Plantation, Book II. ch. 2), corn, beans, squash, fish, lobster, eels, mussels, with berries and nuts for dessert and beer, wine, and “strong water” (liquor) as drink. There were no pies as the pilgrims did not have ovens yet and had no butter nor wheat for crusts.

Conclusion

The pilgrims and the Wampanoag would live peacefully with each other until after the original colonists and Massasoit were dead. Edward Winslow once saved Massasoit's life, and Massasoit was instrumental in returning one of the boys of the colony, who had gotten lost and wound up with the Nauset tribe, back home. Winslow's son, Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680) and Massasoit's son Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676), would face each other as adversaries during King Philip's War (1675-1678) which broke the Wampanoag Confederacy and ended Native American sovereignty in the region as, after the colonists of Plymouth and the other settlements won, Native Americans were sold into slavery, executed, or moved west to reservations.

For a brief time, however, the colonists of Plymouth and the Native Americans held a unique place in history as they banded together to help each other survive in a changing world each needed the other to navigate. Of all the colonies established by the English along the east coast of North America, only the Plymouth Colony honored the treaty they signed with the natives of the land. Later treaties were certainly signed and ratified but were not honored or, if they were, only until they restricted the colonists in taking more land from the natives. Of all the known and little-known facts regarding the pilgrims, this one alone makes them worthy of remembrance, honor, and celebration.