Squanto (l. c. 1585-1622 CE) is the best-known Native American of the pilgrim narrative, famous for helping the Plymouth Colony survive in 1621 CE. He makes up what scholar Charles C. Mann calls the “uneasy triumvirate” of Native Americans who first established a relationship with the English settlers, the other two being Samoset (l. c. 1590-1653 CE) and Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661 CE), the envoy who made first contact with the settlers and the chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, respectively (Mann, 35). Squanto, however, receives the most attention as the “friendly Indian” who was directly responsible for the pilgrims' survival.

There is no denying that, without Squanto's help, the Plymouth Colony would most likely have failed in its first year, but the primary sources do not support the popular vision of the man as the colonists' friend who acted out of genuine concern to help the colony survive. Instead, it seems, Massasoit ordered Squanto to help the settlers after he had signed a peace treaty with them, and Squanto later used his position to undermine Massasoit's authority and stage a coup.

The two chroniclers of the Plymouth Colony, William Bradford (l. 1590-1657 CE) and Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1661 CE), both claim that Squanto was a friend to Bradford, which seems accurate, but this does not mean that the relationship extended to the settlement as a whole, nor that Squanto had any real interest in its survival. The primary sources claim that having returned to his native land after having been kidnapped by the English in 1614 CE to be sold as a slave and finding his entire village wiped out by plague, Squanto was trying to find the means to establish a new life for himself, one in which he was not subservient to anyone, and found a way as guide and interpreter for the Plymouth settlers.

His story is only known through the words of others, however, and any claims concerning his motivation or final goal are therefore speculative. Although Squanto is referenced, often at length, in the letters, journals, and other works of writers of the period, only those by Bradford and Winslow will be addressed in this article due to limited space and considerations of narrative form.

Squanto Before the Pilgrims

Squanto's actual name was Tisquantum (possibly a title, not a personal name) while 'Squanto' was the nickname given him by Bradford (Winslow routinely refers to him as Tisquantum). His story is told in the three works which give the first-hand account of the establishment of Plymouth Colony and its early history:

- Mourt's Relation (Bradford and Winslow, published 1622 CE)

- Good News from New England (Winslow, published 1624 CE)

- Of Plymouth Plantation (Bradford, published 1856 CE)

According to Mourt's Relation and Of Plymouth Plantation, Squanto was a member of the Patuxet tribe of modern-day Massachusetts who kept a seasonal settlement along the coast. In 1614 CE, Captain John Smith (l. 1580-1631 CE) arrived to map the area and establish friendly relations with the natives in hopes of future trade partnerships. The natives of the area were already wary of Europeans after one Captain Harlow had kidnapped a number of them, including the chief of the Nauset tribe, Epenow, in 1610 CE but, according to Smith, they received him well, and he left with reasonable confidence of future trade.

When he set off on his return to England, he left an associate, Captain Thomas Hunt, to conclude the business but Hunt had other ideas and kidnapped 24 natives to sell into slavery in Spain, Squanto among them. When Hunt's ship reached Malaga, he was chastised for the kidnapping, and it seems the prisoners were taken by friars who brought them to the monastery to instruct them in the Christian faith. No details are given regarding Squanto's time in Spain or how he escaped, but he somehow made his way to England where he worked in London for the shipbuilder and merchant John Slane.

At some point before 1619 CE, he was employed by (or with) Captain Thomas Dermer as interpreter for an expedition to Newfoundland. While in Newfoundland, Squanto told Dermer that he would find many willing trade partners among his tribe further south and convinced Dermer to travel down the coast. They arrived at Squanto's old home to find his entire village had been killed by disease and, shortly afterwards, they were taken by Massasoit. Dermer was only spared by Squanto's intervention, but this merely delayed the inevitable since the natives were no longer interested in extending their hospitality only to be betrayed and Dermer was later mortally wounded, finally dying from his wounds when he reached Jamestown. Squanto was kept as a guest (prisoner) of Massasoit.

When the Mayflower arrived in November 1620 CE, the settlers were no more welcome than Dermer had been, and Massasoit's first impulse was to call on the spirits to either kill them or drive them away. After realizing that this was not working as he had hoped, he went with another plan to use the new arrivals to regain his lost status. Massasoit's Wampanoag Confederacy had been the most powerful in the region, exacting tribute from other tribes, until European diseases killed off a significant number of them. By 1620 CE, they had been so reduced that they now paid the Narragansett tribute. An alliance with the immigrants, however, could change the dynamic and so Massasoit decided to make contact and see if the new arrivals could be trusted further than those who had come before.

Squanto Meets the Pilgrims

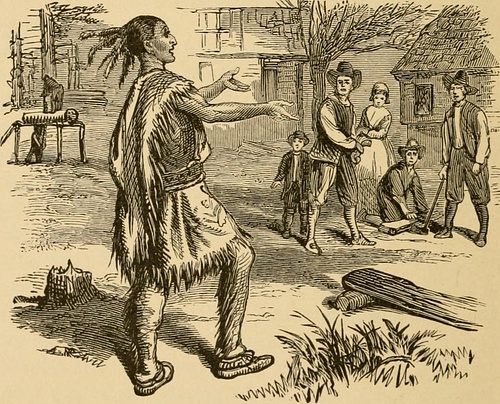

Massasoit had two assets in his village he could send as envoy: Samoset, an Abenaki chief who was being held prisoner, and Squanto, also seemingly a captive, who both spoke English. Massasoit and his right-hand-man, Hobbamock (d. c. 1643 CE), did not trust Squanto, however, and so Samoset was chosen. According to the colonist of the settlement of Merrymount, Thomas Morton (l. c. 1579-1647 CE), Massasoit offered Samoset his freedom in exchange for acting as envoy, and Samoset accepted, arriving at the settlement on 16 March 1621 CE and greeting the colonists in English.

He established a good rapport with the settlers over the next week and said he would return with another who spoke better English than he. The account of the settlers' first meeting with Squanto is given in Mourt's Relation:

Thursday, the 22nd of March, was a very fair warm day. About noon we met again about our public business, but we had scarce been an hour together, but Samoset came again, and Squanto, the only native of Patuxet, where we now inhabit, who was one of the twenty captives that by Hunt were carried away, and had been in England, and dwelt in Cornhill with Master John Slanie, a merchant, and could speak a little English. (55)

Bradford later expands on this account in Of Plymouth Plantation:

His name was Samoset; he told them also of another Indian, whose name was Squanto, a native of this part, who had been in England and could speak English better than himself. [Samoset left and returned later with Squanto who served as interpreter between the colonists and Massasoit in negotiating the peace treaty between them]. After this, [Massasoit] returned to his place, called Sowams, some forty miles off, but Squanto stayed with them, and was their interpreter, and became a special instrument sent of God for their good, beyond their expectation. He showed them how to plant their corn, where to take fish and other commodities, and guided them to unknown places, and never left them till he died. He was a native of these parts, and had been one of the few survivors of the plague hereabouts. He was carried away with others by one Hunt, a captain of a ship, who intended to sell them for slaves in Spain; but he got away for England and was received by a merchant in London, and employed in Newfoundland and other parts, and lastly brought into these parts by a Captain Dermer, a gentleman employed by Sir Ferdinand Gorges and others, for discovery and other projects in these parts. (Book II.ch.1)

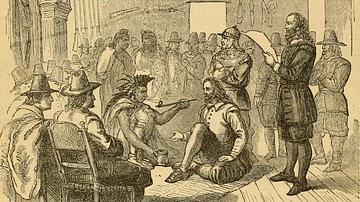

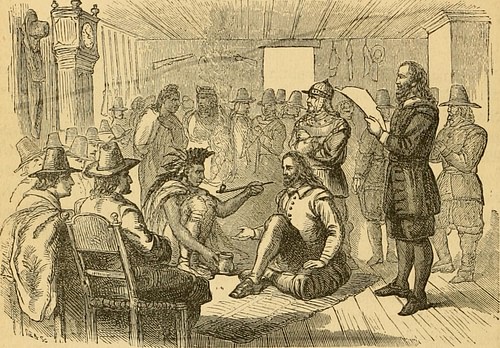

Squanto and Samoset arranged the meeting between Massasoit and the first governor of the colony, John Carver (l. 1584-1621 CE), who signed the peace treaty between the two parties.

The Peace Treaty

Squanto and Samoset also took part in the negotiations and signing of the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty which stipulated:

- That neither he nor any of his should injure or do hurt to any of our people.

- And if any of his did hurt to any of ours, he should send the offender, that we might punish him.

- That if any of our tools were taken away when our people were at work, he should cause them to be restored, and if ours did any harm to any of his, we would do the like to them.

- If any did unjustly war against him, we would aid him; if any did war against us, he should aid us.

- He should send to his neighbor confederates, to certify them of this, that they might not wrong us, but might be likewise comprised in the conditions of peace.

- That when their men came to us, they should leave their bows and arrows behind them, as we should do our pieces when we came to them.

- Lastly, that doing thus, King James would esteem of him as his friend and ally.

(Mourt's Relation, 55-59)

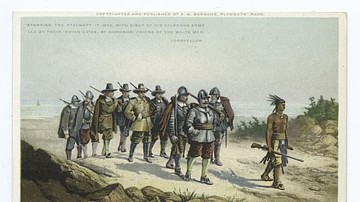

Afterwards, Squanto remained at the settlement to assist the colonists while Samoset disappears from the narrative. Squanto taught the colonists how to plant crops, fish, hunt, and served as their interpreter in establishing trade both with the members of the Wampanoag Confederacy and with other tribes. He regularly accompanied scouting and trade parties on missions along with settlers such as Stephen Hopkins (l. 1581-1644 CE) and the military commander Captain Myles Standish (l. c. 1584-1656 CE), among others. At some point, Massasoit sent Hobbamock and his family to the settlement, presumably to keep an eye on Squanto, and Hobbamock would share Squanto's responsibilities.

Squanto's Attempted Coup

In the fall of 1621 CE, Mourt's Relation and Of Plymouth Plantation report the celebration of a harvest festival, which has come to be known as the First Thanksgiving. The only Native American mentioned by name in Mourt's Relation is Massasoit who is said to have arrived with 90 warriors (and who is never claimed to have been invited), but Squanto and Hobbamock would have also been present at the three-day feast. After the festival, Squanto continues to be referenced as interpreter in trade missions and negotiations but, by 1622 CE, it became clear that he was not actually working for anyone's interests but his own.

He chose a time when the two most effective warriors of the settlement, Myles Standish and Hobbamock, were away on a trade mission (which he also was part of, along with some other colonists) and then had a relative of his arrive at Plymouth, bleeding and claiming to have narrowly escaped Massasoit, claiming the Wampanoag chief was planning to attack any moment. As later revealed, he hoped that Bradford, who by that time had succeeded Carver as governor, would act hastily on the news and launch an attack on Massasoit. Afterwards, it seems, the plan was that Squanto would take Massasoit's place as chief owing to the high regard he was held in by the colonists.

Instead of attacking, Bradford ordered the cannon fired, hoping that Standish and his party was still within earshot and would return; they were and they did, and the story was then relayed to them. Hobbamock, who had already voiced to the colonists his suspicions regarding Squanto, told them the report was a lie because he would have known of any action Massasoit was planning. Hobbamock's wife was sent to Massasoit's village to see if there was any evidence of a war party and reported back there was none and so Squanto's plan was revealed. Bradford writes:

But by what had passed, they began to see that Squanto sought his own ends and played his own game, by frightening the Indians and getting gifts from them for himself, making them believe he could stir up war against them if he would, and make peace for whom he would. He even made them believe the English kept the plague buried in the ground, and could send it among them whenever they wished, which terrified the Indians and made them more dependent on him than on Massasoyt. This made him envied and was likely to have cost him his life; for, after discovering this, Massasoyt sought it both privately and openly. This caused Squanto to stick close to the English, and he never dared leave them till he died. (Book II. ch. 3)

Winslow also relates the incident and provides further detail:

Here let me not omit one notable (though wicked) practice of this Tisquantum, who to the end he might possess his countrymen with the greater fear of us, and so consequently of himself, told them we had the plague buried in our store-house, which at our pleasure we could send forth to what place or people we would, and destroy them therewith, though we stirred not from home. Being upon the fore-named brabbles [disputes], sent for by the governor to this place, where Hobbamock was and some other of us, the ground being broke in the middest of the house, (where-under certain barrels of powder were buried, though unknown to him), Hobbamock asked him what it meant. To whom he readily answered; That was the place wherein the plague was buried, whereof he formerly told him and others. After this, Hobbamock asked one of our people whether such a thing were and whether we had such command of it. Who answered no; but the God of the English had it in store, and could send it at his pleasure to the destruction of his and our enemies. (Good News, 66)

Massasoit, when he heard of Squanto's treachery, demanded he be handed over for execution, but Bradford refused. Squanto was not only his friend but indispensable to the future of the colony. According to the treaty, Bradford had no legal grounds for this action. He claims he was going to honor Massasoit's demands, but a ship appeared on the horizon, which he feared might be French (the colonists' enemy), and only put off handing Squanto over until he could be sure the ship was friendly; after learning it was an English ship, however, there is no mention of his honoring the demands.

Squanto's Death

Bradford's refusal placed a strain on the colonists' relationship with the Wampanoag, but the problem resolved itself when Squanto died, allegedly of a fever, sometime afterwards. Bradford relates the circumstances in Of Plymouth Plantation:

The governor agreed to [a trading mission going 'round the cape]. Captain Standish was appointed to go with them, and Squanto as a guide and interpreter, about the latter end of September; but the winds drove them in and, putting out again, Captain Standish fell ill with fever, so the governor went himself. But they could not get 'round the shoals of Cape Cod, for flats and breakers, and Squanto could not direct them better. The Captain of the boat dare not venture any further, so they put into Manamoick Bay, and got what they could there. Here Squanto fell ill of Indian fever, bleeding at the nose – which the Indians take for a symptom of death – and within a few days he died. He begged the governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen's God in heaven, and bequeathed several of his things to some of his English friends, as remembrances. His death was a great loss. (Book II. ch. 3)

Although Bradford gives the cause of death as "Indian fever", it is possible that Massasoit ordered Squanto's execution by poison, and his agents saw it done. Arguing against this is Bradford's assertion that Standish fell ill with fever shortly before Squanto's death and so it could have been just as Bradford claims and Squanto died of natural causes. This scenario seems a bit too convenient, however, and the speculative claim that he was assassinated has been suggested by a number of scholars in the modern era.

By the mid-19th century CE, the pilgrim narrative had become a foundational myth of the United States, and the figures of Samoset, Squanto, and Massasoit were defined as “good Indians” who had helped the colonists as opposed to “bad Indians” who had resisted the systematic theft of their land and destruction of their culture. The primary documents were available to the public by this time (Mourt's Relation republished in 1841 CE and Of Plymouth Plantation published in 1856 CE), and the story of Squanto was retold without the attempted coup, starting with the help he gave the colony and usually ending with the tale of the First Thanksgiving.

Squanto, or Tisquantum, is more than just the one-dimensional character portrayed at Thanksgiving pageants every year, however, and may have sought to honor the tribe he had lost by making himself chief of another. Even though he acted against them, Bradford characterizes his death as “a great loss” - which is true - but, as important as the primary sources are, without which nothing would be known of Squanto, the loss to history is that his motivations are only given second-hand and will never be fully understood outside of the context of the English narratives which tell his story.