In this interview, Ancient History Encyclopedia is talking to Wendy Orr about her first historical fiction novel set in the Aegean Bronze Age, Dragonfly Song.

Kelly Macquire (AHE): Wendy, thank you for joining me! Do you want to start off just telling everyone a little bit about what the book is about?

Wendy Orr (Author): Aissa is an outcast who is actually the high priestess, the queen's daughter. So, to some extent it is not exactly a retelling, but it jumps off the Theseus legend of Theseus being a sort of hidden son of the king, and that traditional thing of being the outcast and then coming into her own eventually. So, this is on an Aegean island, and this island I actually made up. But what I did was I placed it where Samothrace is. During the writing, occasionally it moved up into the Black Sea, but in the end, I pinned it down, and it was where Samothrace was. Then, for ease and just because I liked it, I actually used a scale model of Samothrace. It is about a tenth of the size, but that let me have a sort of concrete island in my head, while I did not have to have its history.

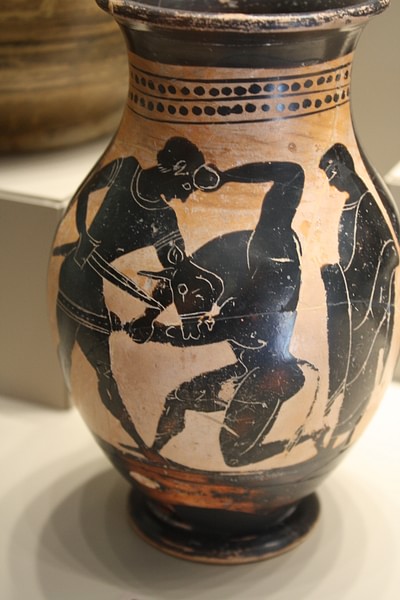

With Dragonfly Song, I used more imagination, but I did a lot of research. And obviously, she goes to Knossos in the end. So, I tried to have all of that part as accurate as I could. Aissa is a young girl, mute from trauma, and she eventually becomes a bull-leaper. I used the Theseus story of the tribute youths going to Crete, and I paired it down because this is such a tiny island. So, she becomes a tribute to go to Knossos and learn the bull-leaping or the bull dances or whatever they were. To me, it seems they had to be a combination of religious ritual and also the excitement of football and sport. I am guessing that not many people survived it. If you did survive, you would be a rock star. I really wanted to play with all that, and I guess that is a sort of mythological feeling of fable, but the history part was really important to me, too.

Kelly: I definitely found the weaving of mythology and legendary history with the archaeology a lot more prominent in Dragonfly Song, and it was a bit more magical, with Aissa and her ability to draw animals to her. What made you want to incorporate a magical element into the novel?

Wendy: You see, again, I often do not know why I have done things in a book. Dragonfly Song took a long, long time to write because I kept feeling that I could not do it because it was too big and because it wanted to be sold in verse. When I started it, it was called the Snake Singer. Actually, I am guessing that it came because of the priestess statues with the snakes. I have thought about these statues for so long, so you start to wonder about the snakes. I thought about cobras and how they dance to the flute and how I spent ages trying to work out how you would sing to snakes to sort of replicate that flute kind of song. I know the snakes are deaf, but they respond to the flute, so obviously, they respond to vibration if they do not hear the noise. Then that broadened into her being able to call other animals but not being able to actually control her gift. It developed very organically, on and off, probably over about five, six years, once I really had this story.

Kelly: I thought it was lovely having these sorts of more iconic and recognizable archaeological stories with the bull-leaping and the snakes, but then bringing in something just a little bit different.

Wendy: One problem when you are writing is that, even if it was purely for adults, you have got to simplify it down because, otherwise, your whole book is nothing but an explanation of how you think Minoan religion might have been, which is actually quite a different book.

Kelly: Must be a difficult balance to manage! As I was reading it, I found that it has got quite a lot of themes that could definitely be brought into a high school English experience such as identity and belonging and self-acceptance. You would not want to take away from such important themes by talking about big questions of their ritual beliefs, which you just could not possibly answer because no one can.

Wendy: No, and it took me ages to research how she made her rope for her sling and things like that. I got onto all sorts of weird mailing lists, and I did this very enthusiastically, and my editor very kindly but firmly pointed out not everybody wanted to read an instruction manual on how exactly to strip the bark, to shred it, to make the rope. Maybe you just need to know that she got the bark, and she made a rope.

Kelly: Why do you choose to write in both prose and verse? It is so lovely, and it works really well. You could come into it thinking that it might be a bit jarring moving from one to another, but I found it very lyrical almost as I was reading it.

Wendy: Oh, well, thank you. I have actually always heard my novels in verse before I write them, and then when I go to write, I have always put them into prose. With this one - and this is what I mean about several years of false starts - I kept trying to write it in prose, and it was not true. But I felt that it was going to be so complex and long and you have to put in a bit of back story.

Kelly: Absolutely.

Wendy: I thought it was just going to be too complex to do in verse. For a year I puzzled with this until finally, I woke up in the middle of one night and, thought "Oh, I'll do it and both". So, I wrote to my editor in the morning and said: "What do you think?" I fully expected her to say no because nobody has done that before. But my lovely editor said "Well, why not? Give it a go!" What actually happened is I probably wrote more of it in verse and then put it back into prose.

Kelly: I know that you went to Crete and you got the chance to research a lot for Swallow's Dance. Did you go there before you finished Dragonfly Song or was that after?

Wendy: It was actually really amazing timing because I finished my final corrections on the proofread on 30 April - I think - and then we flew to Crete on 4 May. I did not have an advance copy even to take with me, but I had a picture of the cover, so I laminated this picture, and I took pictures around Knossos. The real kind of hairs-on-the-back-of-your-neck moment for me was during this incredible day with Dr. Sabina Beckman. I told her with some trepidation about Dragonfly Song. I was sort of making excuses as to why I used the dragonfly motif, and I said it was just that throughout the writing of this book, every time I made a decision or saw what was going to happen, it seemed that I saw a dragonfly within 24 hours. That was when I realized that I not only had to weave them into the story but also that her name would mean dragonfly. Sabina listened to all this, and she said, "but you know, of course, that the dragonfly was one of the symbols of the Minoan artists." I said, "no", and she said, "of course you do, you know this famous fresco." It was one I had never seen or if I had seen it, I had not understood what the figures were on the necklace. So that was such a magical moment for me when she said that.

Kelly: It was meant to be.

Wendy: Yes! So that was quite a different experience to go to Crete, walk through Knossos, and think this is actually the road that my girl walked up. There are different places where they might have had the bull-leaping, but in the end, you sort of choose one for your own emotions. Standing there thinking, "okay I know that I made Aissa up, I know she did not exist, but I truly believe that there were teenagers leaping over bulls in front of a big audience. So, I'm going to say it was in this arena, and that was really phenomenal." In some ways, it was kind of fun to do Dragonfly Song completely from research and imagination. I felt like the only thing that I really got wrong was not realizing how prickly the wild asparagus is.

Kelly: Do you think a reason why you were so interested in writing about the Minoans is that we have got so many images and artifacts from them but no text there, so there was potentially more chance for imagination and creative leeway versus writing on a culture that we know a lot about?

Wendy: I am not sure; that is a really good question. I suspect that if I had started this in an organized way and decided I would write about one period of history and this will be it, I might have felt that that was too loose. I mean, when I was a child, I always thought I was going to write about Roman Britain like Rosemary Sutcliff, who was my big hero as a child and still is. And certainly, with the Romans, there is a lot more text. But yes, I think, maybe it was the psychological puzzle or the freedom to interpret it yourself that has drawn me in. That is interesting; nobody has asked me that before and I had not thought about it, but I do wonder because I love reading different theories, and I am very easily swayed. Then I go back, and I think, no, human beings do not act like that. That does not make sense to me, just like I do not think the Minoans were all sweetness and light, even if they had a high priestess.

Kelly: Or despite the lack of fortifications, there was probably still war.

Wendy: I thought that maybe there is no fortification here, but it was actually a totally defensible natural bit, and actually, maybe there are remains of a wall here.

Kelly: Or potentially they were just so confident in their dominance and their strength and their navy that they did not think they needed them.

Wendy: Exactly. If you have a really powerful navy you may not need to defend all parts of your island. How come there are myths of them getting tribute and everything if they did not have a powerful navy? I think they probably had a high priestess; I feel very convinced of that. Whether she was the only ruler, I also doubt.

Kelly: Yeah.

Wendy: And whether that made everything sweet and light, I really doubt. I was in college in London when Margaret Thatcher was the education minister before she was prime minister, but I do not remember anybody saying this is the softest prime minister we have ever had. I like being able to wiggle around and think this makes sense to me, but also weighing it up with, if not facts exactly, but knowledge approximating the facts as clearly as we can. For example, the fact that nobody agrees with when the Santorini eruption was. You know, for years it was 1450 BCE.

Kelly: And now, it is 1628 BCE.

Wendy: Exactly.

Kelly: And that changes the whole timeline of what people thought was happening and why they thought it was happening. It just completely ruins it, and I think it is fantastic.

Wendy: I love that. It certainly also lets me say this is what I have decided, and if all the really eminent people cannot even decide about this date, then I can make up my mind about some things. One of the reasons that I thought I was so lucky to have this friendship and mentoring from Sabina was that she was an ecological archaeologist. So, her passion was recreating things. She built her own Minoan house.

I will tell you another creepy story. I sent my editor the first draft, or part of the first draft, a short enough section that she could read in two hours. When you send stuff to an editor they might be really bogged down and might not hear from them for weeks. I got an answer a couple of hours later, and when I read this, and I had just come back from walking in the Treasury Gardens, and I looked up and there were dragonflies everywhere.

Kelly: Wow! The world was telling you that you are on the right track, you know, you are doing a good thing. Do you hope that this book and Swallow's Dance as well, will make kids, younger students be more familiar with these different types of history earlier on? Do you hope that they will open up more of history for kids?

Wendy: Oh, I hope so. I do not really care if they are interested in knowing ancient history, I just want kids to be aware that there are other worlds, real worlds. Even though there is that fantastical element, it is not fantasy. People actually lived here before you, people lived in different ways, but they still had the same feelings that you do, and they were just as real as you, and pain hurt them just as much. They may have believed quite differently, but they still felt the same. So, what I also hope is if you are looking at something as far removed as Minoan Crete and you can identify with a character there, then perhaps you can also start to identify with other people in your world now.

Kelly: Thank you so much for joining us, Wendy. It has been a pleasure. Dragonfly Song is highly recommended, especially for those lovers of the Minoans!