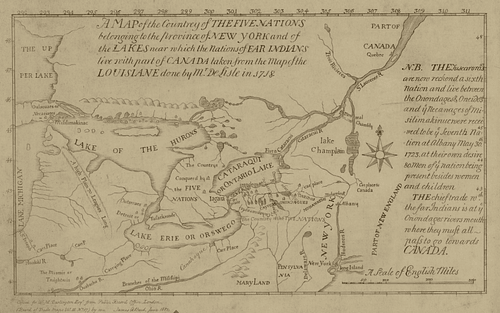

The Haudenosaunee, also known as the Iroquois Confederacy, Iroquois Five Nations, or the Iroquois League, was one of the most powerful Native American polities north of the Rio Grande. They arrived in the historical record in the 16th-century CE when European colonists began interacting with the Haudenosaunee's five constituent nations – the Onondaga, Mohawk (who called themselves the Kanienkehaka), Cayuga, Oneida, and Seneca – in both war and trade. The Haudenosaunee as a nation had a huge impact on the colonial and revolutionary, and Early Republic eras of the United States as well as on the early history of Canada – not to mention their importance in indigenous geopolitics before and after European colonization of the Americas.

Despite their importance to history, how and when the Huadensaunee confederacy began has become a matter of much debate over the decades. The Haudenosaunee themselves have a long-standing oral tradition that describes the origins of their famed confederacy, as well as the constitution the five nations created upon forming this league. Yet, this tradition gives no indication as to the exact year these events occurred. In an attempt to shed light on the matter, many scholars have turned to archaeology and clues hidden in the historical record to determine the date the Haudenosaunee formed.

Hiawatha & the Great Peacemaker

According to Haudenosaunee oral histories, a long time ago, the nations that would one day form their confederacy were at constant war with one another. A Seneca man named Hiawatha lost his wife and daughters to this violence. Inconsolable, he began to wander, and somewhere in the Kanienkehaka's territory, he came across a man named Dekanawida.

Known as the Great Peacemaker, Dekanawida is credited with the vision of uniting the Iroquois nations and bringing peace to their lands. Like many prophets throughout history, the historical figure of Dekanawida has had many miracles attributed to him. According to tradition, prior to his birth, Dekanawida's mother received a vision in a dream that she would conceive a son and he would go on to plant the Great Tree of Peace. Nine months later, still a virgin, she gave birth to Dekanawida. Worried about the child's seemingly supernatural provenance, Dekanawida's grandmother urged her daughter to kill him. Though they tried to drown the infant twice, he returned both times.

While we know very little of the historical Dekanawida, it is clear that he was not Haudenosaunee by birth. Born in the Wendat Nation of southern Ontario, Dekanawida seems to have left his home for reasons unknown. When he enters the story of the Great Peace, we find him living with the Kanienkehaka, the easternmost of the Haudenosaunee nations, where he meets Hiawatha.

When Dekanawida saw the grief from which Hiawatha suffered, he offered to help, performed what would come to be known as the condolence ceremony; first drying the eyes of the weeping Hiawatha, then opening the ears of the grieving man, and lastly, clearing Hiawatha's throat. Now able to see, hear, and speak, Hiawatha could take in and understand Dekanawida's vision for a great peace, and the two men then set out together to spread the word.

Bringing the Nations Together

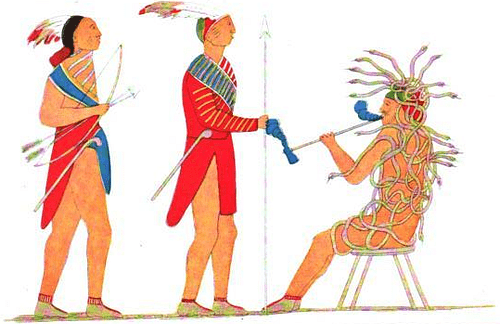

To demonstrate the advantages that peace posed, the Great Peacemaker would take a single arrow in his hands, and show how easily it could be snapped in half. He would then take a bundle of five arrows, representing each of the five nations that would form the Haudenosaunee, and show how, even with great effort, this bundle would not break. The Oneida, Seneca, Kanienkehaka, and Cayuga accepted this message of peace and agreed to join the confederacy. The Onondaga, however, needed more convincing.

During their first visit to the Onondaga, a leading member of the nation who was also believed to be a powerful shaman, named Tadodaho, turned Hiawatha and the Peacemaker away. The rest of the Onondaga assured them that, if they could convince Tadodaho of their message, their nation would join the confederacy. Unable to convince the shaman, Hiawatha and Dekanawida left to speak with the other Haudenosaunee nations farther west. After securing peace with these nations, they returned to the Onondaga and Tadodaho.

According to tradition, whenever Hiawatha and Dekanawida drew close to Tadadaho, the shaman would cause evil happenings to occur. When the Great Peacemaker enlisted the help of others to persuade Tadadaho, the shaman used his abilities to hurt or even kill them. After a great struggle, Hiawatha and the Peacemaker were able to penetrate Tadadaho's defenses and help him clear his mind. After the Peacemaker did for Tadodaho what he had done for Hiawatha, the shaman could once again see reason, renounced evil, and agreed to join the confederacy. The Haudenosaunee confederacy was now complete.

Planting the Tree of Peace

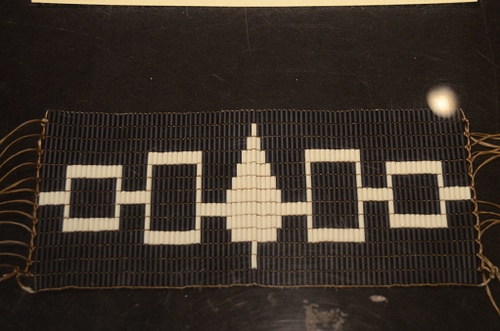

To cement the confederacy, the Haudenosaunee planted a tree, known as the Tree of Great Peace. According to the Haudenosaunee Constitution, which was preserved orally for hundreds of years before being written down in the 19th century CE, Dekanawida and the Five Nations' Confederate Lords planted the tree. A metaphor for the Great Peace itself, the Haudenosaunee recorded how "roots… spread out from the Tree of Great Peace, one to the north, one to the east, one to the south, and one to the west. The name of these roots is the Great White Roots and their nature is Peace and Strength" (Murphy, Constitution, Art. 2).

Interestingly, the Peacemaker planted the Great Tree in Onondaga territory. While the tradition of Hiawatha and the Peacemaker tells us Tadodaho was an evil shaman bent on challenging the message of peace, perhaps the historical Tadodaho was simply a powerful man hoping to retain his power, either through the continued independence of the Onondaga or by elevating his nation's place in the confederacy through negotiation. If this is true, his tactics seemed to have worked. The first line of the Haudenosaunee constitution reads:

I am Dekanawidah and with the Five Nations' Confederate Lords I plant the Tree of Great Peace. I plant it in your territory, Adodarhoh [another name for Tadodaho], and the Onondaga Nation, in the territory of you who are Firekeepers. (Murphy, Constitution, Art. 1)

This was no small declaration; the Onondaga would act as the Confederacy's capital – specifically, the village of Ganondagan. Further, Firekeepers formally opened and closed "all councils of the Confederate Lords" and passed "upon all matters deliberated upon" before rendering a decision. (Murphy, Constitution, Art. 8) Apart from their role as the capital nation, the Onondaga had secured an important position for themselves within the new confederacy.

Dating the Origins of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy

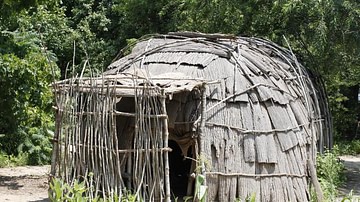

Despite the rather epic nature of this oral history, it does not discuss when the events occurred that lead to the formation of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy. The story of the Peacemaker contends that prior to the Great Peace warfare was endemic among the Haudenosaunee nations. Beginning in 900 CE, a culture called the Owasco by archaeologists moved into the area that would eventually house the Haudenosaunee. Their settlements were planted on hilltops, a fair distance from waterways, typically a mile or two away. The archaeological record shows that a few centuries after the Owasco arrived in the area, Iroquoian peoples, the ancestors of the Haudenosaunee, also began settling there.

The Iroquoian peoples also built settlements on hilltops several miles from streams or lakes. Their towns were heavily fortified, with two or three layers of palisades surrounding them, which were typically 12-20 feet tall. Additionally, evidence has been found which suggests that between 1300-1400 CE Iroquoian towns began to consolidate within these hilltop hamlets. This evidence suggests that war had become a reality of life for the Owasco, if not among themselves then potentially with the incoming Iroquois, and then the Iroquoian nations that replaced them.

Archaeologists have also found evidence of economic exchange within the five Haudenosaunee nations as well as homogenization of material culture among the Haudenosaunee that suggests greater ties between the nations. By dating these artifacts, most scholars place the founding of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy sometime in the mid- to late 15th century CE.

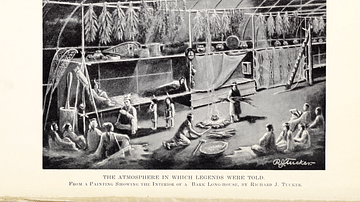

In the Haudenosaunee oral history of how their confederacy came to be, the Seneca received a 'sign in the sky' to ratify the Great Peace. Scholars from the University of Toledo, Jerry Fields and Barbara Mann, felt this could be used to challenge the scholarly consensus of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy forming in the 15th century CE. According to their theory, the 'sign in the sky' the Seneca had seen was a solar eclipse. Using this data, Mann and Fields searched for solar eclipses that had occurred in western New York state at the site of the treaty's ratification, Ganondagan. Their findings showed that a solar eclipse had indeed occurred in Ganondagan, but not in the 15th century CE. Rather, they found the eclipse had taken place in August 1142 CE some four centuries earlier than most scholars believe the Haudenosaunee came together.

Conclusion

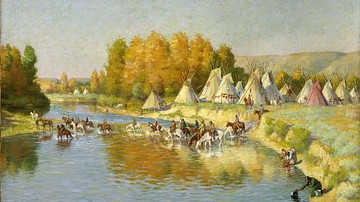

No matter when the Haudenosaunee Confederacy formed, their impact on history cannot be denied. In the decades following their formation, they became one of the most influential Native Nations of the American northeast. The wake of European colonization, however, brought significant changes to all Native Nations. As contact with European colonists increased, countless Native Americans lost their lives, and as the Haudenosaunee fought against the French in Canada and traded with the Dutch and English in New York, they could not keep out disease and warfare either.

The increased need to replace the members of their society led to a period dominated by mourning wars, essentially raids on neighboring nations with the intention of bringing back prisoners to be adopted into Haudenosaunee society. As disease and war became a way of life in the Americas for decades, if not centuries, the Haudenosaunee came into conflict with Native Nations as far west as Illinois and Michigan. This irrevocably altered Native American geopolitics, even resulting in the diaspora of some nations, such as the Wendat.

In the early 1720s CE, the Tuscarora, an Iroquain people originally from central and eastern North Carolina, moved north to join the Haudenosaunee. When the American Revolution began, however, the Confederacy was split. The Oneida and the Tuscarora sided with the Americans; the other four nations allied with the British, believing the British Empire could better keep colonists out of their land. After the war, the Haudenosaunee (including the Oneida and Tuscarora) were forced into signing a treaty with the new United States, which saw them cede large portions of their territory. Despite this, modern scholars now believe that their confederacy's constitution proved extremely influential on the Founding Fathers and how they conceived of a modern democracy.