According to Luke's Acts of the Apostles, the last thing Jesus did before he bodily ascended to heaven was to commission the disciples to 'witness' to his teachings. 'Disciple' meant 'student' and was derived from the various schools of philosophy in the ancient world. There was a master/teacher, and his students collected the teachings and passed them on. From this point forward in the text, however, the term 'disciple' is often replaced by 'apostle'. 'Apostle' (from the Greek 'apostellein' meaning "one sent out") was a herald. The Latin for 'apostle' was 'missio', from which we derive our word 'missionary'.

The apostles were sent out with good news (evangelion in Greek). This became the basis for the later Anglo-Saxon term for 'good news' - 'gospel'. In terms of narrative function, while designated disciples of Jesus initially, when the story takes them from Jerusalem to other areas of the Eastern Empire, they become apostles. They announce the good news that God's final intervention in history was imminent, the fundamental teaching of Jesus.

The Disciples/Apostles

The gospels reported that Jesus called his disciples in the manner of God calling the traditional prophets of Israel for their missions. The first followers were fishermen from the region of the Sea of Galilee and were usually called in pairs. The traditional list of Jesus' 12 disciples includes:

- Peter

- Andrew (Peter's brother),

- John (son of Zebedee)

- James (son of Zebedee),

- Philip,

- Nathaniel,

- Matthew (Levi),

- Thomas,

- James Alpheus

- Judas Alpheus,

- Simon (the Zealot),

- Judas Iscariot.

However, the lists do not always match. Luke reports 70 disciples in pairs of twos and John has Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea as followers. Nevertheless, this group was consistently referred to as 'the Twelve', despite the numbers and different names. The number symbolized the twelve restored tribes of Israel. The prophets had proclaimed that God's intervention would restore the tribes of Israel (now scattered among the nations) and bring them back to the land.

Mark, Matthew, and Luke all reported that during the arrest, the trials, and the crucifixion, all the disciples abandoned Jesus. John alone claimed that "the beloved disciple" stayed with Jesus at the foot of the cross. Later Christians identified "the beloved disciple" as John. The gospels and Acts report that during the post-resurrection appearances by Jesus the disciples were forgiven for their lack of understanding and abandonment. We have evidence that within 20 years of the death of Jesus, a group that included James, Peter, John, & others (as reported in Galatians 2 and Acts 15) was in place in Jerusalem.

In both Mark and Matthew, the angel in the empty tomb told the women that Jesus would meet them in the Galilee. Luke and John have resurrection appearances in and around Jerusalem. The end of Matthew contains what is now deemed the Great Commission:

Therefore, go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything I have commanded you. And surely, I am with you always, to the very end of the age. (Matthew 28:16-20)

This is not an early form of the Trinity and could have been added to manuscripts of Matthew only after that concept was invented in the 4th century CE.

Another source for the motive of the disciples is found in Acts 2. Luke related that during the festival of Pentecost, the spirit of God appeared as fire to the disciples. The disciples were speaking in their own dialect of Aramaic, but Jews from all over the known world heard them in their own tongue. It was the power of this spirit that enabled the disciples to be successful in their preaching, as well as the ability to work miracles.

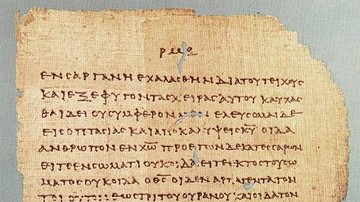

Our sources for reconstructions of the activity of the missionaries are found in Paul's letters (written c. 50s and 60s CE), the Acts of the Apostles (written c. 95 CE), and some of the other New Testament letters of the 1st century CE. Beyond the Christian writings, we do not have contemporary literature from other Jews or non-Christians in this period.

The narrative of Acts follows the opening parameters of the order: the apostles preach in Jerusalem, all Judea (in the cities of Joppa and Haifa), Samaria, and the ends of the earth. Acts relates the travels of Paul in Asia Province (Turkey), Syria, and Greece. The book ends with Paul in Rome, not quite "the ends of the earth" but the ultimate center of the Roman Empire. Unfortunately, if any of the original disciples wrote anything, it has not survived. The consensus understands that fishermen from the Galilee most likely were not educated in Greek reading and writing. Luke provides many detailed speeches, particularly by Peter. However, the speeches in Acts are the product of the author. On the other hand, some scholars claim that the Lukan speeches reflect what would have been typical speeches of the apostles.

Peter “the Rock”

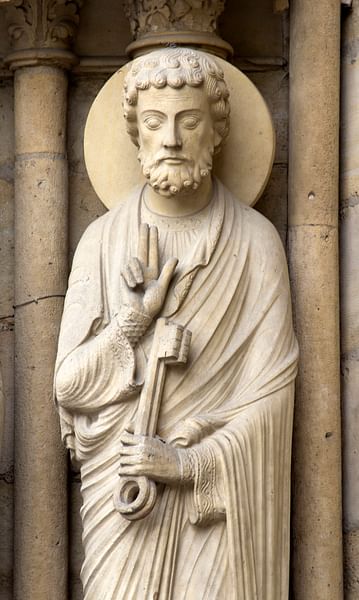

It is only in Matthew's gospel that we find the basis for later traditions concerning Peter:

When Jesus came to the region of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples, "Who do you say I am?" Simon Peter answered, "You are the Messiah, the Son of the living God." Jesus replied, "Blessed are you, Simon son of Jonah, for this was not revealed to you by flesh and blood, but by my Father in heaven. And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock, I will build my church, and the gates of Hades will not overcome it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven; whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven." (16:13-20)

The text plays upon the name Peter, petra meaning 'rock' in Greek). Having the power of "the keys of the kingdom of heaven" meant that Peter is the ultimate source of who gets into heaven. The Catholic Church utilizes this passage to claim direct spiritual descent from Peter to the Pope. The symbol of crossed-keys on the papal crown appears in sculptures throughout Vatican City.

The Methods of the Apostles

To reconstruct the earliest Christian communities, the scholarly consensus agrees that this was a Jewish message and so the followers of Jesus took his teachings to the synagogues first. For centuries Jews had established communities throughout the Roman Empire and synagogues were at the center of their religious and community life. Non-Jews, also known as Gentiles, however, showed a higher rate of interest than the Jews.

The Gentile interest came from the group that Luke labeled God-fearers, non-Jews who were attracted to Jewish values, charity, ethics, and stories. Synagogues were not sacred spaces (that was only found in the Temple complex in Jerusalem) and so there was no bar to their participation. This Gentile interest surprised many and debate began about how to include them. Those who believed that these people should fully convert to Judaism first (with circumcision, dietary laws, and Sabbath rules), are labeled Jewish-Christians by scholars. Those who accepted Gentiles as Gentiles are labeled Gentile-Christians.

Galatians 2 and Acts 15 describe a meeting that was held in Jerusalem to decide the issue. The decision was taken that they could join the assemblies of Christ-followers, but only if they followed Jewish incest laws, avoided meat with blood in it, and ceased the worship of all the other gods (idolatry). This became known as the first Apostolic Council.

Paul, Apostle to the Gentiles

The one apostle we know the most about was Paul, a Pharisee who had opposed this new group. He had a vision from Jesus (in heaven), who told him to be “the apostle to the Gentiles.” Paul the Apostle had never met Jesus when he was on earth, but he claimed that this vision authorized him to have the same standing as the original disciples (as an apostle). Paul traveled to many cities of the Eastern Roman Empire, where he established communities of believers.

For Paul, Gentiles come in as Gentiles. The prophets of Israel had said that in the final days of God's restoration some Gentiles would turn and worship the God of Israel. This turning, he claimed, demonstrated their repentance in turning from the great sin of idolatry. Paul's letters indicate that he was an educated Jew, not only well-versed in the scriptures, but well-versed in the concepts of higher learning in the Roman Empire through the schools of philosophy. He combined both in his arguments. Because of the absence of any writings of the original disciples, we cannot determine if they taught using the same methods and arguments as Paul.

While a decision had been taken in Jerusalem concerning the Gentiles, apparently the debate continued for several decades. It is one of the main topics in Paul's letters, where he often accuses false apostles of attempting to undo what he had preached. He does not name these false apostles and scholars assume that this group represented those who formed the first community in Jerusalem: Peter, James, and John (Jewish-Christians). By Paul's own admission, there was no love lost between him and this group. He sarcastically referred to them as the "so-called pillars" of the community (Galatians 2). On the question of Gentile inclusion, it remains unknown exactly what each of the original apostles taught in their travels. We know that Gentiles began to outnumber Jews by the end of the 1st century CE, and without written evidence, we have to assume that the original disciples accommodated their inclusion.

Paul's letters also reveal the debates and tensions in the first communities, both internal and external. Jews in the cities of the Empire had long ago worked out an accommodation with their neighbors. The new teaching of no idolatry had the potential to upend relationships vis-à-vis Rome, and it led to the official persecution of Christians by the end of the 1st century CE. Some of Paul's letters are written from prison, and Acts related various times that Paul was imprisoned for civil disturbances. In Acts, however, a sympathetic Roman magistrate always releases Paul.

The Sufferings of the Apostles

The gospels all have Jesus predicting that his followers would suffer persecution from both the Jews as well as the governing authorities. In the Acts of the Apostles, we have stories of their constant harassment and arrest. Luke claimed that Peter and John were arrested several times by the Sanhedrin (the Jewish city council) and were imprisoned. This was followed by their miraculous escapes.

Luke also related the story that Herod Agrippa I (r. 41-44 CE as king of the Jews) decapitated James, the brother of John. He was later struck by a lightning bolt from God for his hubris of thinking himself divine. This story of Herod Agrippa is also found in the writings of Josephus, a 1st-century CE Jewish historian. However, Josephus does not mention the death of any Christians. Josephus also related the death of James, Jesus' brother by the Sanhedrin (62 CE), a story which is absent in the Acts of the Apostles.

New Testament Letters & 2nd-century CE Legends

Some letters eventually became canonized in the New Testament and claim to be written by the first disciples, 1 and 2 Peter and 1, 2, and 3 John. The Petrine letters are introduced by Peter the Apostle and are addressed to communities in Asia Province. The letters remonstrate against false prophets and encourage perseverance in the light of persecution in that area. Of note is the admonition to "honor the Emperor" and not make waves (1 Peter 2:17).

Many scholars challenge both the authorship and date of the Petrine letters. The writer utilizes an advanced level of rhetoric and philosophy in his arguments which cannot be credited to a Galilean fisherman. Equally problematic is the fact that official persecution of Christians by Rome most likely began under Roman emperor Domitian (r. 83-95 CE) and not during the lifetime of Peter.

There are three letters assigned to John, but authorship remains a topic of debate. The tradition claims that they were written in Ephesus toward the end of the 1st century CE by John the Elder. This individual was understood to be the "beloved disciple" of the fourth gospel (and the author of that text), John, the brother of James.

In the 2nd century CE, literature began to appear that filled in details of the activity of the apostles. Many of these are titled acts of the apostles, meaning deeds. They narrated their travels, their teaching, their miracles, their sufferings, and eventual deaths. The acts follow the style and structure of what is known as Greek Romance Literature. These novels were popular and usually related stories of lovers who undergo separation and adventures but are reconciled in the end.

One of the most elaborate is The Acts of Peter. The story follows his travels throughout the Roman Empire and his last years in Rome. It provides more details of Nero's (r. 54-68 CE) alleged persecution of Christians after the fire in Rome (64 CE), a story that was only first attested by Tacitus c. 110-115 CE). The Christians of Rome encouraged Peter to flee and save his life because of his importance as a witness. He left Rome along the Appian Way where he saw a vision of Jesus coming toward him. He asked, "Quo vadis, domine?" ("Where are you going, Lord?") and Jesus told him that he was on his way to Rome to die again. Peter then knew what he had to do, as an atonement for his prior denial of Jesus. He turned around, was arrested, and died in the amphitheater that Nero used that night to execute Christians. This is the source of the story that he asked his executioners to crucify him upside down, as he was not worthy to die in the same manner. Thus, Renaissance art depicts the death of Peter this way. The site of Peter's vision is marked along the Appian Way as a pilgrimage stop.

During the 2nd century CE, Christian writers attempted to define and explain Christianity to the Roman authorities. Their teachings were validated upon the premise that the material was handed down from the original apostles to these successors (bishops) in the cities. The writings of this second generation were collectively named the 'Apostolic Fathers' in the 17th century CE. These epistles and treatises became important in the eventual determination of what became orthodoxy in the 4th century CE.

The Deaths of the Apostles

Historically, we cannot confirm how the apostles met their deaths. But by the 2nd century CE, the tradition claimed that they all died as martyrs. This concept was directly borrowed from Judaism, from the story of the Maccabean Revolt against Greek rule (167 BCE). Following the stories of the brothers in 1 Maccabees, Christians applied the same rationale to anyone who died for their faith. The reward was instantly being taken up into heaven.

By the 4th century CE, Christians made pilgrimages to the traditional sites and tombs of the apostles. It was understood that the apostles, now in heaven, could serve as mediators between God and Christians and could be petitioned in prayer. This became known as the cult of the saints, where it was claimed that all the original apostles were now in heaven. Stories, known as martyrologies that detailed the arrest, conviction, and suffering of these individuals, were created, and many of these utilize the template of the suffering and death of Jesus so that his disciples are understood to have died in imitation of Christ.