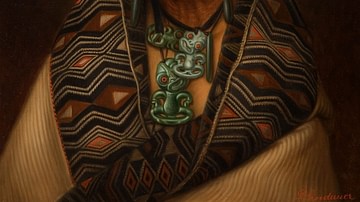

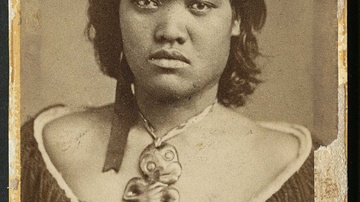

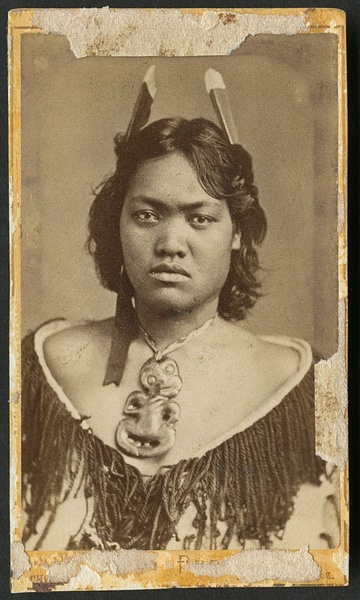

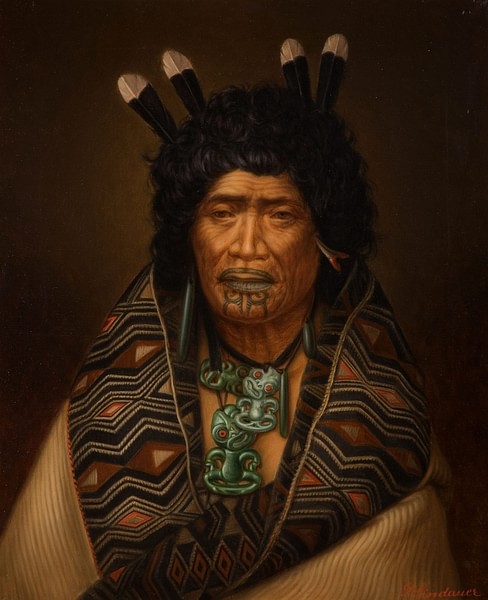

The hei tiki is a small personal adornment, fashioned by hand from tough pounamu (New Zealand greenstone or nephrite jade), and is worn around the neck. Hei means something looped around the neck, and tiki is a generic word used throughout Polynesia to denote human figures carved in wood, stone, or other material.

The cultural history and mythology of the tiki are important to the geographic area in Remote Oceania called the Polynesian triangle, which encompasses Aotearoa (New Zealand), Hawaii, and Easter Island as its corners and includes more than 1,000 islands.

These islands have various forms of tiki in common. There are ancient stone and wood carvings of tiki in the Marquesas, first noted in 1595 CE with the arrival of Europeans to the Marquesan Archipelago, and the word tiki appears in Polynesian languages. While it is tiki in Aotearoa and the Cook Islands, it is ti'i in Tahitian and ki'i in Hawaiian.

As a cultural expression, the greenstone hei tiki ornament worn by the Maori of Aotearoa is globally recognised, but what may not be known is the long history of the hei tiki, which is specific to New Zealand.

The Supernatural & Physical Origins of the Hei Tiki

Strictly speaking, tikis are large humanoid figures carved in wood or stone and were used to guard the entrances to places considered tapu (sacred) or to protect sites. On Easter Island, for example, over 200 monolithic humanoid statues known collectively as Mo'ai were discovered in 1722 CE by the Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen (1659-1729 CE). These statues (except for seven) face away from the ocean and look toward the villages of the Rapa Nui people, guarding over them. Similarly, the Maori of Aotearoa would place intricately carved wooden tiki figures at the entrance to a pa (fortified village) or marae (meeting ground).

In the Marquesas, tiki statues have been found with carved hands resting on protruding stomachs. The ancestral belief in this part of Polynesia is that ritual knowledge, genealogy, and oral tradition are held in the stomach, and the tiki's hands protect memories and sacred traditions.

In Polynesian mythology, tiki often represents the first human being on Earth created by the atua (deity) Tane, who, together with Hine-ahu-one, is considered humankind's progenitors. In areas of Polynesia, carved tiki figures were often thought to be a repository for a certain god's mana (prestige). An example is the Hawaiian tiki atua Kanaloa, who was the ruler of the sea realm and embodied the ocean's power (Tangaroa is the Maori equivalent).

The hei tiki – a cultural object worn around the neck - is considered a taonga tuku iho (treasured heirloom) because each hei tiki is handed down from one generation to the next and emotionally connect to the memory of tupuna (revered ancestors). No two hei tiki are alike and each one has its own personality imbued with wairua (spirit).

Ancient origins for the hei tiki lie in Hawaiki (the ancestral homeland of Maori, thought to be in the East Polynesian islands). A Maori legend tells of the explorer Ngahue who had a disagreement with his wife. He fled Hawaiki but was chased by the fearsome fish, Poutini, and they made landfall in the Bay of Plenty (North Island of Aotearoa). Poutini fell into a deep pool and was turned into a greenstone canoe. Ngahue returned to Hawaiki with a piece of the pounamu taken from Poutini, which he fashioned into the first hei tiki adornments.

A Southeast Asian influence has also been posited. Horatio Gordon Robley (1840-1930 CE), a soldier in the British Army who had grown up in India and Burma (present-day Myanmar), arrived in New Zealand in 1864 CE. He noted similarities between the hei tiki and Buddha figures, particularly the position of the in-turned legs and hands. Hand-drawn illustrations showing Robley's view of the hei tiki's evolution can be seen here.

The supernatural origins of these stories and beliefs credit the source of tiki mana to Polynesian deities and creation narratives, but the physical origin of hei tiki is uncertain because of the lack of archaeological evidence.

As a treasured taonga, hei tiki would be cared for and handed down within a family, so there are relatively few archaeological finds. It is most likely that early pounamu hei tiki pendants appeared c. 1550-1600 CE (a Maori history date range known as the Classic Period). The Classic Period is characterised by single-pendant adornments fashioned from pounamu and often curvaceous in style, whereas the Archaic Period (pre-1450 CE) featured necklaces often worn together with pendants. Archaic adornments were also made from softer materials such as ivory, shell, and serpentine.

Around 23 hei tiki were found in the former pounamu working village of Whareakeake on the Otago Peninsular (Aotearoa) by 1900 CE. Whether these were trade tiki (for trade with other Maori iwi or tribes) or to meet the new demand from European collectors is unknown.

Earlier, Archaic-period tiki pendants - although archaeological examples are few and far between - are quite different in style, featuring more angular lines, upright head, hands resting on the chest, abbreviated legs, and many different looks. The New Zealand anthropologist, H.D. Skinner (1886-1978 CE), sketched examples of the Archaic style hei tiki with the earliest dated example being a drawing of a hei tiki from Doubtless Bay (Aotearoa) by the French explorer J. F. M. de Surville (1717-1770 CE) in 1769 CE. Te Papa Tongawera, New Zealand's national museum, has an online collection of tiki from both the Archaic and Classic periods.

What can be established from historical records is a stylistic leap occurred during the 16th century CE from the Archaic to the Classical style when hei tiki was increasingly fashioned from pounamu using toki (an adze) also made from pounamu. These adzes were highly-prized possessions in their own right and were taonga handed down through the generations.

Hei Tiki Use & Meaning

The German ethnologist Karl von den Steinen (1855-1929 CE) gave his opinion on the artistic merit of the hei tiki when he said the Maori adornment was "perhaps the ugliest object the artistic genius of a people ever created by years of labour" (quoted in Skinner, 309).

The squat, humanoid appearance of the hei tiki with its enlarged head (about one-third the size of the figure) and prominent eyes is, however, a significant output of Maori creativity, but did the hei tiki mean anything beyond oha tupuna or heirloom worn in fond remembrance of ancestors?

It has been suggested that during funerals and times of grief, the hei tiki was used as a surrogate for the deceased when the body could not be recovered, and it was placed on the ground, sung to, and wept over. When a person of status died, such as a chieftain, the hei tiki was buried with the body and recovered at a later time (during the hahunga or ceremony for shifting the bones) when it was believed to have increased mana and special value.

The hei tiki is also strongly associated with female fertility, and women would wear it during pregnancy and to encourage easy childbirth. The enlarged head of the tiki shape and contortion of limbs suggests the tiki is a human embryo and possibly that of an unborn child (a particularly powerful spirit). Early European visitors, however, saw men wearing the hei tiki, which suggests that it was considered a personal adornment with a connection to revered ancestors.

The hei tiki was also used as a protective talisman. During the 1814-1815 CE visit to Whangaroa, John Liddiard Nicholas (1784-1868 CE), who accompanied the Reverend Samuel Marsden (1765-1838 CE) on one of his journeys to Aotearoa, noted a taua (war party) of around 150 men who were wearing hei tiki around their necks.

Common Visual Characteristics & Types of Hei Tiki

Robley, in 1915 CE, noted two types of hei tiki. The first type is known as Robley Type A with the tiki head resting on the shoulders, and with both hands positioned on the thighs. Type B is rarer with the tiki head raised, showing a defined neck cut free of the shoulders, and with one hand raised to the chest or mouth and the other remaining on the thigh. Type B hei tiki also lack ribs, and one shoulder is hunched. Both types may be seen on the Te Papa blog.

Some hei tiki are carved with the head inclining to the right and some to the left. There does not appear to be any particular significance to this, but the common 45-degree angle of the head tilt was well-established by 1769-1777 CE. The head tilt may also be due to the use of the rectangular adze blades used to cut and carve hei tiki.

The typical large eyes were made from paua shell (abalone) or filled with red sealing wax of European origin.

In the 1960s CE, a theory was proposed by American orthopaedic surgeon Charles O. Bechtol (1912-1998 CE), who considered the hei tiki shape might represent nine congenital deformities. Bechtol studied available photographs, drawings, and hei tiki at the Smithsonian Institution, the Chicago Natural History Museum, and the Bishop Museum in Honolulu. He concluded that the tilted head is due to torticollis – a condition in which the muscles of the neck spasm and twist, causing the head to lean at an odd angle. The hunched shoulder he attributed to Sprengel's abnormality, and the three toes and fingers typical of the hei tiki Bechtol thought could be syndactylism (a fusing of digits). Congenital club foot was the reason he gave for the feet of the hei tiki pointing toe-to-toe.

Interesting medical observations, but there is no evidence to suggest that Maori fashioned the hei tiki to represent abnormalities. Instead, the evidence points to the hei tiki as taonga with complex layers of cultural interpretation.

Hei Tiki Colours

New Zealand pounamu has a wonderful translucent quality with different colour combinations. When pounamu is heat-treated, the hardness of the material is strengthened, and when the surface is ground, a pearly white, grey-green colour with a silver sheen is revealed. This colour is known as the inanga variety and was prized by Maori, along with kawakawa (named after the dark green leaves of the native kawakawa plant). Kahurangi is a vibrant apple green with high translucency, kokopu has reddish-brown to blue tones with distinctive brown speckles, while Tangiwai is an olive blue-green. Tangiwai is bowenite although it was included in the pounamu category. It was rarely used to fashion hei tiki because it is softer than pounamu.

A hei tiki collection studied by Dougal Austin, Senior Curator Matauranga Maori at Te Papa, showed a clear preference for the inanga variety of pounamu, with 65 percent of hei tiki made from this variety, while 15 percent were heat-treated.

From Pounamu to Plastic

Toward the end of the late 19th century CE, hei tiki had become part of mainstream culture with many pakeha settlers (New Zealanders of European origin) wearing them as personal adornments and manufacturing hei tiki. The notion of the mana of the whanau (family) residing in the hei tiki and being a connection to revered ancestors (and a cultural object in its own right) was replaced by commercialism. Aotearoa saw the rise of a pakeha jewellery industry, particularly in Dunedin (South Island), and a colonial reinvention of the hei tiki. Numerous hei tiki were also lost to overseas private collections.

Between 1867-1938 CE, 50,000-100,000 imitation tiki were made from greenstone in Germany by a well-known jewellery manufacturing company and were imported back into the New Zealand market. Hei tiki could be mass-produced (often from plastic) with cost efficiency in industrialised cities such as Birmingham in the United Kingdom.

To a great extent, the misappropriation of hei tiki mirrors the declining fortunes of Maori during the 19th century CE. By 1896 CE, the Maori population was approximately 42,000. Although exact figures are uncertain, the pre-European Maori population estimated by Captain James Cook (1728-1779 CE) in 1769 CE was around 100,000. The population decline was due to disease, loss of land to European settlers, and casualties of Maori-colonial wars (1840s-1870s CE).

By the early 20th century CE, the hei tiki had become a lucky charm and an imperial object. At least one greenstone hei tiki set sail in 1905 CE with the All Blacks (New Zealand rugby team) bound for a tour of Great Britain. The tiki image was synonymous with sporting prowess and a burgeoning pakeha or broader South Pacific identity.

New Zealanders took the hei tiki to war – prisoners of war in a camp in Millwitz, Poland, produced the camp newsletter, The Tiki Times, the escort trawler H.M.S. Lord Plender always carried with them a block of wood carved with a tiki design, and The Beatles were given large plastic tikis in 1964 CE when the band toured Aotearoa.

The word tiki had entered the popular Western lexicon and was a pop culture icon with the opening of tropical-themed tiki bars illuminated by flaming tiki torches. Tiki movies such as Hei Tiki (1935 CE), Pardon My Sarong (1942), South Pacific (1958), and Blue Hawaii (1961) enthralled cinema audiences with their glimpses into a world filled with cool trade winds, palm-thatched huts, and Polynesian maidens bathing beneath waterfalls.

Cultural Resurgence

By the 1970s CE, fascination with hei tiki as pop culture, lucky charms, and sporting mascots had given way to serious attention being paid to contemporary expressions of hei tiki as a Maori art form, with young Maori hei tiki carvers like Rangi Kipa (b. 1996 CE) using Corian (manufactured by DuPont) as a bridge between Maori and pakeha understandings. Pounamu carries with it cultural meaning, whereas newer materials such as Corian, or working in whalebone and ivory, make hei tiki accessible to a broader New Zealand identity.

Although there are many hei tiki still in private "tribal art" collections around the world (and are therefore disconnected from their whakapapa), young Maori artists will create a contemporary art form that will hopefully see hei tiki restored as a taonga.