A Model of Christian Charity is a sermon delivered by the Puritan John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE), second governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, either just before or after his ship, the Arbella, set sail from England for North America in 1630 CE. The sermon has become famous for the passage in which Winthrop compares the colony to a 'city on a hill', a reference to the biblical passage from Matthew 5:14 in which Jesus Christ encourages his followers by telling them, "You are the light of the world. A city that is set upon a hill cannot be hidden," meaning that all the world would be illuminated by the light of the Christian message and would look toward Christians to provide that light.

In this same way, Winthrop believed that the colony he and his followers were establishing would shine like a beacon to the world and, if they were faithful to this vision, would bring all people to Christ while, if they failed, they would become worthy of the world's scorn and God's displeasure.

The sermon informed the establishment and governance of the Massachusetts Bay Colony as well as its policy toward religious dissent. In his sermon, Winthrop emphasized the importance of a collective, unified effort in making the colony a shining 'city on a hill', and anyone who challenged that vision was not tolerated. Among the best-known dissenters were Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) and Anne Hutchinson (l. 1591-1643 CE) who were both banished, but there were others who were asked – or ordered – to leave when it became clear they would not conform to the Puritan vision.

In the 20th century CE, the 'city on a hill' reference was invoked by President John F. Kennedy (served 1961-1963 CE) and President Ronald Reagan (served 1981-1989 CE) alluding to the United States of America in general. The sermon is considered one of the primary inspirations for the concept of American exceptionalism – the belief that the United States is superior to other nations – which has informed the self-image and governmental policies of the nation since its establishment.

Puritan Migration & Colonization

Puritanism was a response to a perceived lack of reform in the Anglican Church. The Protestant Reformation (1517-1648 CE) broke the unity of the Catholic Church and Protestant sects in Europe formed diverse denominations, which rejected the practices, orders, and policies of Catholicism. King Henry VIII of England (r. 1509-1547 CE) joined the Reformation, not from a sincere interest in religion, but because he wanted to divorce his wife, and this was forbidden by the Catholic Church. In response to the Church denying him the right to divorce, he formed his own – the Anglican Church – but had no great interest in making major reforms other than replacing the pope with the English monarch and some superficial changes in worship and the role of priests.

Puritans were Anglicans who objected to the retention of Catholic practices and beliefs by the new Church. The term was originally a derogatory slur given by mainstream Anglicans to those who claimed the Church should be 'purified'. The Puritans referred to themselves as 'saints'. Puritans continued to serve in significant positions as clerics and would attend services but quietly (and sometimes not so quietly) advocated more drastic reform to bring the Anglican Church in line with the model of the early Christian community as depicted in the biblical Book of Acts. By the time of the reign of Elizabeth I of England (1558-1603 CE), Puritans were forming their own congregations, which met in secret because such gatherings were against the law. Since the monarch was the head of the Anglican Church, any dissent or criticism of the Church was considered treason.

Under James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE), Puritans were persecuted with fines, imprisonment, and execution and many fled to the Netherlands where the government was more tolerant of religious diversity. One such congregation, which was comprised of Puritan Separatists (those who believed the Church was completely corrupt and so separated themselves from it) settled in the city of Leiden, the Netherlands, but when they found that James I could reach them even there, they left for North America aboard the Mayflower and founded Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620 CE. Plymouth Colony became the first successful English colony established in New England and encouraged others to follow them.

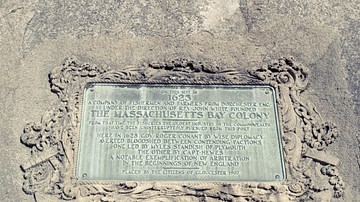

In 1630 CE, an expedition was financed by the Massachusetts Bay Company to expand upon a colony established in 1628 CE by the Puritan Separatist John Endicott (l. c. 1600-1665 CE), its first governor. John Winthrop was elected by the company to take over from Endicott and left England with four ships and 700 Puritan colonists for the promise of the New World where they would be free to worship as they pleased.

This expedition was the first in what became known as the Great Migration (or Puritan Migration) which would eventually bring over 20,000 colonists to North America between 1630-1640 CE. Winthrop delivered his sermon either just before leaving or, as traditionally believed, after his ship, the Arbella, had left England. The purpose of the piece was to impress upon the colonists the importance of their mission which Winthrop interpreted as a commission from God, a covenant between the colonists and the divine, which could not fail.

A Model of Christian Charity

Winthrop had good cause for concern since earlier colonies had been begun successfully only to be abandoned. The Popham Colony was established in the region of present-day Maine in 1607 CE and failed after only 14 months. The Plymouth Colony lost 50% of its population in the winter of 1620-1621 CE and would have failed if not for the intervention of the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy. In 1623 CE, a settlement at Cape Ann was established and abandoned two years later. Winthrop was determined that his colony would not suffer the same fate, and he made his determination clear through his sermon.

A Model of Christian Charity begins by establishing the nature of human existence, claiming that God is in control and everything happens for a reason. Some people are meant to be rich, some poor, some are supposed to rule, others are to be ruled. This, Winthrop claims, is in conformity with the natural world in which there is no equality among animals. Further, this order is divinely mandated so that the Holy Spirit might better work among the rich to care for the poor and with the poor to accept such care humbly to the greater glory of God. In this ordered world, everyone had need of everyone else, but it was not one's own greatness of character which made one rich nor any deficit in a person that made one poor, but all was predestined to glorify God. Winthrop writes:

All men being thus (by divine providence) ranked into two sorts, rich and poor; under the first, are comprehended all such as are able to live comfortably by their own means duly improved; and all others are poor according to the former distribution. There are two rules whereby we are to walk one towards another: Justice and Mercy. These are always distinguished in their act and in their object, yet may they both concur in the same subject in each respect. (Hall, 166)

A rich man may fall into trouble and require help from the poor, and the poor, of course, should gratefully accept assistance from those more affluent. In order to walk with Justice and Mercy in accord with one another, one must follow the golden rule as given in the biblical Book of Matthew 7:12: "Whatsoever you would have that men do unto you, do also unto them." One is only able to follow this rule, however, if one is aware of and accepts God's unconditional love. This love is given freely by God through Jesus Christ and, as Winthrop notes:

From the former considerations ariseth these conclusions:

- First, this love among Christians is a real thing, not imaginary.

- This love is as absolutely necessary to the being of the body of Christ, as the sinews and other ligaments of a natural body are to the being of that body.

- This love is a divine spiritual nature, free, active, strong, courageous, permanent, undervaluing all things beneath its proper object, and of all the graces this makes us nearer to resemble the virtues of our heavenly Father. (Hall, 167-168)

Having established God's love as the binding force among them, Winthrop goes on to propound the elements which make up their present mission:

- The People

- The Work

- The End

- The Means

He then goes on, one by one, to discuss each aspect. The people are fellow Christians who are "knit together by this bond of love and live in the exercise of it" and so are as a single family of believers (Hall, 168). The work before them is different from other colonies or churches which have been established in the past because their mission has been undertaken "by a mutual consent through a special overruling providence", in other words, God himself has ordained their mission and they have accepted the responsibility (Hall, 168). The end, Winthrop stresses, "is to improve our lives to do more service to the Lord, the comfort and increase of the body of Christ whereof we are members that ourselves and posterity may be the better preserved from the common corruptions of this evil world" (Hall, 168). The means to accomplish this end is a "conformity with the work and end we aim at," which must be undertaken seriously and with dedication, unlike other churches which only pretend at devotion, and the means will produce the desired end if the colonists "love one another with a pure heart" and "bear one another's burdens [looking] not only on our own things, but also on the things of our brethren" (Hall, 168). Winthrop emphasizes the importance of the means in that there has never been a more important end to achieve since the days of the biblical patriarchs.

Winthrop then explains why this is so in describing their mission as a covenant with God, just as binding as any covenant depicted in the Bible, which will bring great rewards if honored but dire punishments should it be broken. Winthrop writes:

Thus stands the cause between God and us, we are entered into covenant with him for this work, we have taken out a commission, the Lord hath given us leave to draw our own articles we have professed to enterprise these actions upon these and these ends, we have hereupon besought him of favor and blessing. Now, if the Lord shall please to hear us, and bring us in peace to the place we desire, then hath he ratified this covenant and sealed our commission. (Hall, 169)

Once the covenant is ratified, Winthrop says - as in once they have landed safely at their destination - the responsibility for keeping it is upon the colonists, and failure is not an option:

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us; so that if we shall deal falsely with our God in this work we have undertaken and so cause him to withdraw his present help from us, we shall be made a story and a by-word through the world, we shall open the mouths of enemies to speak evil of the ways of God and all professors for God's sake; we shall shame the faces of many of God's worthy servants, and cause their prayers to be turned into curses upon us till we be consumed out of the good land whither we are going. (Hall, 169)

Winthrop ends the sermon by quoting the patriarch Moses and encouraging his fellow colonists to choose life in adhering to the vision he has imparted so that they may all prosper in the land God has given to them.

Influence on the Colony

The sermon achieved its end as evidenced by the dedication of the colonists in keeping the covenant by, first, building the settlements. Everyone, including those who were elected magistrates, worked together to build their own homes as well as those of others and public buildings. Winthrop rejected Salem, which had been established by Endicott in 1628 CE, as capital and founded Boston as the center, with other settlements – Cambridge, Charlestown, Dorchester, Medford, Roxbury, and Watertown – following swiftly afterwards. Unlike Plymouth Colony, the casualty rate of the first year was low – 200 deaths out of 700 – and the Massachusetts Bay Colony was already thriving by 1632 CE.

This conformity continued to be observed after the initial settlement in adherence to the acceptable code of behavior set down by the magistrates. Those who continued to work toward the common goal of success and prosperity were welcomed; those who sowed dissent and threatened unity were expelled. The first famous example of this was the separatist preacher Roger Williams who criticized the colony on theological and moral grounds as well as condemning the Plymouth Colony. Williams felt Winthrop's colony was too legalistic and not in keeping with the spirit of God and objected to both colonies taking land from the Native Americans without paying them. He was banished in 1635 CE and founded his own colony, Providence, in modern-day Rhode Island, which he purchased from the local natives.

In 1637 CE, the midwife Anne Hutchinson was brought before the court for undermining ecclesiastical authority and subverting 'true teachings' and was banished in 1638 CE; she followed Williams and founded Portsmouth, Rhode Island. Others were banished as well in the interests of maintaining the original vision of complete cohesion and conformity to the covenant the colonists believed they had forged with God and were required to honor.

Conclusion

A Model of Christian Charity, although frequently cited today in encouraging Christian congregations or elevating the status of the United States in speeches, applied only to those Christians who believed as Winthrop did and behaved as he understood a Christian should. Others who believed differently were not tolerated and were punished with exclusion not only from the colony but, as far as the Puritan theology was concerned, from the grace of God, consigning them to damnation. When the image of the 'city on a hill' has been invoked since in referencing the United States, its original meaning and context is almost always omitted.

The United States prides itself on inclusion and freedom for all citizens and a welcoming policy toward immigrants no matter their nationality or religion, but the original English settlers were interested in neither of these. The Puritan 'city on a hill' was not inclusive but exclusionary and elitist. It was only after the Puritans lost their spiritual and political hold on the region that this paradigm would change although, as recent history shows, the exclusionary practices of the Puritans remain beneath the veneer of the welcoming, inclusive, self-image the United States continues to claim for itself.