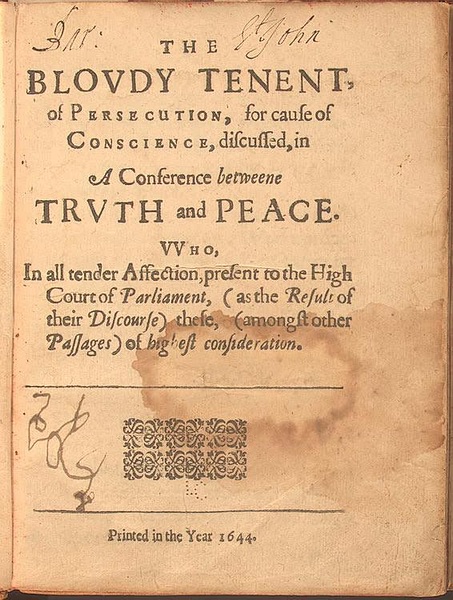

The Bloody Tenent of Persecution (original title, The Bloody Tenenent of Persecution for Cause of Conscience) is a 1644 CE book by the Puritan separatist Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683 CE) which is best known for its arguments supporting the separation of church and state. Williams believed that sincere religious devotion was poisoned by political policy and any governmental influence on religion could only be detrimental. This is the opposite of how the concept of the separation of Church and State is understood in the modern era when it is recognized as a preventative against religion adversely affecting political policy.

Williams was banished from Massachusetts Bay Colony for holding "strange opinions" which ran counter to the views of the magistrates of Boston. He afterwards founded the colony of Providence Plantation (modern Providence, Rhode Island) and returned to England in 1643/1644 CE to secure a charter for his colony. It was while he was there, waiting for the legal machinery to provide him with the charter, that he wrote The Bloody Tenent of Persecution as an answer to the magistrates of Boston who had banished him and one of them in particular, the Reverend John Cotton (l. 1585-1652 CE), whom he singled out as holding especially dangerous views concerning theocratic government.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony's government appeared to be a democratic republic in which officials were elected by popular vote but, in reality, was a theocracy (government informed by a specific religious belief) because no official could hope for election who did not support the legalistic religious views and practices of the colony. Williams claimed that no elected official of a government had authority over the religious beliefs and conduct (insofar as it was based on one's beliefs) of the citizenry. Governments only had authority over civil matters; the Church alone should preside over ecclesiastical concerns and one's individual beliefs were that person's own business.

The Bloody Tenent of Persecution was burned in England when it was published in 1644 CE and sparked a literary duel between Williams and Cotton over the next few years arguing the twelve central claims of Williams' book. The work informed the philosophy of the colony of Providence and, eventually, proved influential in the formation of the government of the United States of America, notably in the Bill of Rights concerning the separation of church and state.

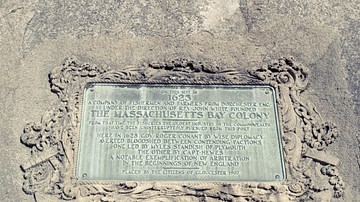

Massachusetts Bay Colony

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was established in 1630 CE in the first wave of what is known as The Great Migration (also The Puritan Migration, 1630-1640 CE) during which Puritans, fleeing persecution in England, left their homeland to settle in the region of New England, North America. The Plymouth Colony had been established in 1620 CE by Puritan separatists and, after its success, other colonies were founded, Massachusetts Bay being among the first.

The Puritans flocked to the New World in order to practice their faith freely without fear of persecution by civil authorities. The Anglican Church had replaced the Catholic Church in England, substituting the monarch for the pope, and since the monarchy was the head of the new church, any criticism of church policy or practice was regarded as treason. Puritans objected to the retention of aspects of Catholicism in the Church and wanted to see it 'purified', but some Puritans went further, declaring the Church wholly corrupt, and insisting believers separate themselves from it and form their own, independent, congregations; these people were known as separatists.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony was informed by the vision of the English Puritan lawyer John Winthrop (l. c. 1588-1649 CE) who envisioned it as a 'city upon a hill' which would be a model of Christian piety for the rest of the world. This model could only be fully realized, he claimed, if everyone in the colony conformed to the same vision of what it meant to be a Christian and worked together toward a single goal. Winthrop made his vision clear in his sermon A Model of Christian Charity delivered to the colonists before they reached the New World and impressed upon them the importance of complete conformity in thought, word, and deed. The colonists, Winthrop said, had made a covenant with God in agreeing to become part of the expedition and, if they kept this covenant, would be rewarded by divine blessings; if they did not, they could expect God's well-deserved wrath.

Williams & the Boston Magistrates

Williams arrived in Boston, the capital of the colony, in 1631 CE with a reputation as a powerful Puritan preacher but quickly fell out of favor with Winthrop and the other magistrates owing to his unorthodox views. As a separatist, Williams did not approve of the Puritan vision of retaining ties to the Anglican Church in order to 'purify' it from within and advocated for complete separation. More importantly, however, he disagreed with the legalism of the Puritans of Boston and maintained that the practice of one's religion was up to the individual who was granted liberty of conscience by God himself to pursue whatever course in belief one thought best.

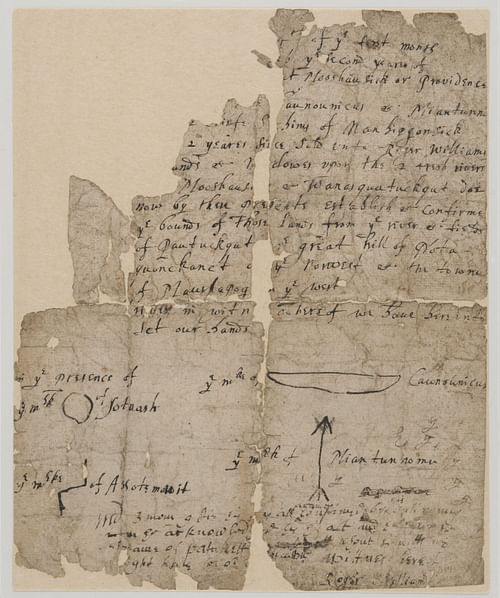

After coming into conflict with the Puritans, Williams left to find a new home with the separatists of Plymouth Colony but, after two years, found them just as intolerant and legalistic. During this time, he made friends with the Native Americans of the Wampanoag Confederacy as well as other tribes in the region such as the Narragansetts, learning their language and listening to their complaints about the new arrivals in their land. He wrote a tract criticizing colonial policy in which he claimed that King James I of England (r. 1603-1625 CE) had no rights in granting land to the Plymouth Colony and neither had King Charles I of England (r. 1625-1649 CE) concerning Massachusetts Bay. These lands had been stolen from the Native Americans, Williams noted, and no further colonies should be established without proper compensation to the Native Americans, the land's rightful owners.

Williams returned to Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1633 CE and accepted a position as assistant pastor and then as pastor of the church at Salem. That same year, he was called to court to answer for this tract as well as other "strange opinions" he had been sharing with his church at Salem. John Winthrop presided over the hearings and John Cotton sat in judgment among the other magistrates. Between 1633-1635 CE he was called to court a number of times and warned to stop spreading dissent among his congregation and the magistrates went so far as to pressure the Salem church to oust Williams to keep him from preaching. Their efforts included a document claiming civil government had authority over religious matters (the work known as A Model of Church and Civil Power). Williams resigned his position to spare his congregation trouble but continued voicing his opinions as he always had until he was banished and fled the colony, narrowly escaping deportation back to England, in 1636 CE.

He founded Providence Plantation on land he purchased from the Narragansett tribe, paying them their asking price, and established a colony based on complete religious freedom. Unlike Massachusetts Bay, where conformity to a single vision was considered vital to spiritual and communal success, Providence emphasized the individual and encouraged people of all faiths to settle there. In 1643 CE, Williams returned to England to secure a charter for the colony in order to prevent its takeover by Massachusetts Bay. While there, with time on his hands, he wrote two of his most famous works, A Key into the Language of America (the first book on Native American language and customs in English) and The Bloody Tenent of Persecution for the Cause of Conscience; the latter in answer to the magistrates of Boston generally and John Cotton specifically.

The Bloody Tenent of Persecution

The book is a dialogue between Truth and Peace, both protagonists, discussing the biblical passage from Matthew 13:24-30, 37-43, the so-called Parable of the Sower:

The kingdom of heaven is like a man who sowed good seed in his field. But while everyone was sleeping, the enemy came and sowed weeds among the wheat and went away. When the wheat sprouted and formed heads, then the weeds also appeared. The owner's servants came to him and said, 'Sir, did you not sow good seed in your field? Where then did these weeds come from?' 'An enemy did this', he replied. The servants asked him, 'Do you want us to go then and pull them up?' 'No', he answered, 'because while you are pulling the weeds, you may uproot the wheat with them. Let both grow together until harvest. At that time, I will tell the harvesters: First collect the weeds and tie them in bundles to be burned; then gather the wheat and bring it into my barn.' (Matthew 13: 24-30)

Matthew 13:37-43 goes on to explain how the wheat is the people of the Kingdom of Heaven and the weeds are those who pursue sin and cause disruption; at the final judgment, God will determine the wheat from the weeds. Williams' two protagonists make clear that it is up to God to determine this, not any Christian magistrate, and, further, that no political official should claim authority over areas – such as one's religious faith and whether one is ultimately a "wheat" or a "weed" – because government can only administrate civil, not religious, matters. When government takes it upon itself to root out those it considers weeds, it is overstepping its authority since the Bible makes clear God has prohibited this.

This dialogue is only a part of the work, however, and Williams makes this clear in his preface, which, in the present day, is often printed as if it were the complete book because it presents all of the arguments Williams later develops in his twelve sections. The preface reads:

First: That the blood of so many hundred thousand souls of protestants and papists, spilt in the wars, of present and former ages, for their respective consciences, is not required nor accepted by Jesus Christ the Prince of Peace.

Secondly: Pregnant scriptures and arguments are throughout the work proposed against the doctrine of persecution for the cause of conscience.

Thirdly: Satisfactory answers are given to scriptures and objections produced by Mr. Calvin, Beza, Mr. Cotton, and the ministers of the New English Churches, and others former and later, tending to prove the doctrine of persecution for the cause of conscience.

Fourthly: The doctrine of persecution for the cause of conscience is proved guilty of all the blood of souls crying forth for vengeance under the altar.

Fifthly: All civil states, with their officers of justice, in their respective constitutions and administrations, are proved essentially civil, and therefore not judges, governors, or defenders of the spiritual, or Christian, state and worship.

Sixthly: It is the will and command of God that, since the coming of his Son the Lord Jesus, a permission of the most Paganish, Jewish, Turkish, or anti-Christian consciences and worships be granted to all men in all nations and countries; and they are only to be fought against with that sword, which is only, in soul matters, able to conquer: to wit, the sword of God's spirit, the word of God.

Seventhly: The state of the land of Israel, the kings and people thereof, in peace and war, is proved figurative and ceremonial and no pattern nor precedent for any kingdom or civil state in the world to follow.

Eighthly: God requireth not an uniformity of religion to be enacted and enforced in any civil state; which enforced uniformity, sooner or later, is the greatest occasion of civil war, ravishing of conscience, persecution of Christ Jesus in his servants, and of the hypocrisy and destruction of millions of souls.

Ninthly: In holding an enforced uniformity of religion in a civil state, we must necessarily disclaim our desires and hopes of the Jews' conversion to Christ.

Tenthly: An enforced uniformity of religion throughout a nation or civil state confounds the civil and religious, denies the principles of Christianity and civility, and that Jesus Christ is come in the flesh.

Eleventhly: The permission of other consciences and worships than a state professeth, only can, according to God, procure a firm and lasting peace; good assurance being taken, according to the wisdom of the civil state, for uniformity of civil obedience from all sorts.

Twelfthly: Lastly, true civility and Christianity may both flourish in a state or kingdom, notwithstanding the permission of diverse and contrary consciences, either of Jew or Gentile. (Preface, 1-2)

Commentary

Williams' main point throughout is that political intervention in religious matters is not only bad for religion but also for government as it causes civil unrest (clearly expressed in his eighth point concerning civil war). Whenever a political agenda is joined to religious ideals, both the government and the faith are degraded and the people suffer. Scholar Frank N. Magill sums up the book's basic message:

Within the setting of a civil society, Williams' argument goes on, a church has the same nature and status as a medical society or a business corporation. A religious society has its own functions, which are distinctly separate and different from those of a civil society. Civil harmony and order are the responsibility of the state and not of the Church. Christians have a duty as Christians to protect the purity and integrity of their churches, but they have no warrant whatsoever for ridding civil society of Jews, Muslims, pagans, and others who do not properly belong in the Church. Such persons are clearly qualified for full membership in civil society. (437)

The book was addressed specifically to John Cotton because Williams believed (wrongly) that Cotton had been the main author of the document A Model of Church and Civil Power, which had been sent to the church at Salem by the Boston magistrates in 1635 CE when they were pressuring the church to dismiss Williams as pastor. Cotton, actually, had nothing to do with this work, but it did express his views that the state could, and should, enforce conformity with the religious views of the majority of the citizenry in order to preserve unity and harmony of spirit.

Conclusion

The work criticized the English monarchy regarding its policies of colonization of North America as well as those of the colonies established thus far and so was burned by order of the king when it was published in England in 1644 CE. Orders were given for Williams to be arrested but, by that time, he had already left on the return trip to Providence. Enough copies of the book survived to circulate among the public, however, and Williams brought others with him back to New England. Cotton read the book and responded with a refutation justifying his position which only encouraged Williams to write a second work refuting Cotton's apologetics in 1652 CE.

Neither Cotton nor Williams ever conceded any major points in the argument, and Massachusetts Bay continued to operate as a theocracy while Providence maintained its vision of individual religious rights as a true democratic republic in which any male citizen over the age of 21 could be elected to public office regardless of their religious convictions. The Bloody Tenet of Persecution would later influence the philosophical writings of John Locke (l. 1632-1704 CE) whose vision informed the Founding Fathers of the United States of America, especially Thomas Jefferson (l. 1743-1826 CE), one of the framers of the U.S. Constitution and Bill of Rights. In the present day, the work is considered a classic on religious freedom and the necessity of the separation of church and state for a stable and inclusive civil society.