During the 1st century CE, a sect of Jews in Jerusalem claimed that their teacher, Jesus of Nazareth, was the 'messiah' of Israel. 'Messiah' meant 'anointed one', or someone chosen by the God of Israel to lead when God would intervene in human history to bring justice to the world. Jesus was crucified by a Roman magistrate, Pontius Pilate, c. 30 CE for proclaiming a kingdom that was not Rome's. Shortly after his death, his followers claimed that he was resurrected from the dead and was now in heaven at the right hand of God. Those who followed the teachings of Jesus ('Christ', the Greek for 'messiah') would also earn resurrection in the afterlife.

This message (the 'good news' (gospel) of the kingdom) was spread by his followers to the cities of the Eastern Roman Empire and beyond. The initial reaction was one of shock and confusion. The hero of the story was not only dead, but dead by crucifixion, the Roman punishment for treason. Paul recognized how radical this was by referring to "the scandal of the cross" (1 Corinthians 1:23).

During their travels, the missionaries encountered non-Jews (the Gentiles of the New Testament), who wanted to join the movement. The apostles decided that the Gentiles did not have to convert to Judaism, and they quickly outnumbered Jewish followers. However, these Gentiles had to cease idolatry, which upended the age-old concept that one's religion was the way one lived one's life, the customs of the ancestors handed down by the gods. Transferring one's allegiance to the new group not only required a lifestyle change but often divided families. From the evidence of Paul's letters and the Acts of the Apostles, such teaching led to civil disturbances, and by the end of the 1st century, Rome began to persecute and execute these people for this teaching.

Hero Cults & the Imperial Cult

Sometimes half-human, half-divine, Greek heroes such as Hercules had performed great deeds in life, and after their death, they were believed to be among the gods or in the Elysian Fields in Hades. This process was known as apotheosis ('to deify'). Several towns claimed to have the tombs of these heroes where people made pilgrimages to pray. These sites incorporated the social aspect of patron/client relationships, the obligations between the social classes. The heroes could serve as mediators at the court of the gods for the benefit of their communities. Hence, they were patron gods/goddesses. The Romans first borrowed the idea at the tomb of Scipio Africanus who defeated Hannibal in the Second Punic War (218-201 CE).

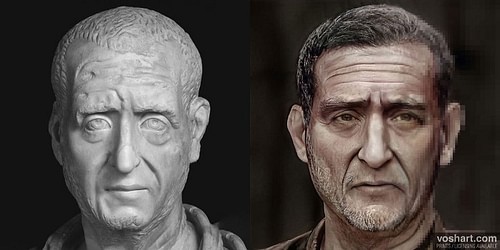

The imperial cult arose after the assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE as the common people left tokens at the site where they burned his body in the Forum. Julius died with no legitimate son and named his great-nephew, Octavian, as his adopted, legal heir, the future Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE). When a comet appeared over the city during the funeral games, the people and Augustus proclaimed this a sign that Ceasar was now a living god. The Roman Senate condoned an official cult, which also benefitted Augustus who was now the son of a god. From this point on, most Roman emperors were deified upon their death.

After the Battle of Actium and the end of the civil wars in 31 BCE, the eastern client-kings petitioned Augustus to allow them to build temples and worship him. He recognized the fiscal and propaganda advantage of these temples and so granted permission. They were to be temples to the goddess Roma where people could pray for the welfare of the Roman Empire and the first family.

The Great Fire of Rome & the Jewish Revolt

Nero (r. 54-68 CE) became infamous as the first Roman emperor to persecute Christians. When he was accused of starting a devastating fire in Rome in 64 CE, to allay suspicions, he blamed the Christians. He arrested them and invited the displaced poor to a banquet and show where Christians were tortured and crucified. This is when Peter allegedly died upside-down on a cross. Although the site, Vatican Hill, later became the basilica of St. Peter's church, the story is problematic because we have no eyewitness testimony for these events. The earliest source is the Roman historian Tacitus (56-120 CE), writing c. 110 CE. If, in fact, Nero did this, he was on his own. There was no official policy concerning Christians.

When the Jews revolted against the Roman Empire in the year 66 CE, Nero sent the future emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79) to take care of it. Vespasian was battling in Galilee when Nero committed suicide in 68 CE. A turbulent time, known as the Year of the Four Emperors (69 CE), followed, and when Vespasian emerged victorious, he left his son Titus in charge of the rebellion. In the year 70 CE, Titus (r. 79-81 CE) laid siege to Jerusalem and destroyed the Jewish Temple. Jews had traditionally donated to the upkeep of the Temple; this amount would become a Jewish tax they would now send to Rome as war reparations.

The Crime of Atheism

Vespasian's second son, Domitian (r. 81-96 CE), renewed all the old policies that usually got emperors killed. He quickly went through the treasury and then remembered his father's Jewish tax, the collections of which had been neglected. Domitian sent the Praetorian Guard to scour the tenements looking for Jews to pay up. This is most likely when Rome became officially aware of people who followed the Jewish god but were not Jews and nor did they follow the Roman religion, the customs of the fathers.

Domitian insisted upon being addressed as 'Lord and God', and he ordered everyone in the Empire to worship at the imperial cult temples with sacrifices in the form of cash donations. Christians, however, refused to obey this command and, as a result, were charged with atheism. Atheism meant disbelief in the gods and, at the same time, it was a civil crime against the state. Not respecting the state cults meant that you did not want the Roman Empire to prosper. Angering the gods in such a way could bring on natural disasters and wars, and therefore, atheism was equivalent to treason, and the punishment was death. This is how and why Christians were executed in the arenas. Jews were exempted from the state cults by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE) as a reward to his Jewish mercenaries among his legions in the East.

A second charge related to the Roman social/religious assemblies known as collegia. These were groups who shared common interests or trade skills. Members met under the egis of a god or goddess for a shared meal, however, collegia had to have permission from the government. Christians did not have this license to assemble, and therefore, it was an illegal religion.

Our first evidence of a Christian trial comes from Pliny the Younger (61-112 CE), the governor of the province of Bithynia c. 110 CE. In a letter to the emperor Trajan, he reported that after he arrested some Christians, he brought in some statues of the gods and a bust of the emperor. The ones who refused to throw a pinch of incense while taking an oath were executed. Trajan answered that if Christians openly defied the system, they should be arrested but should not be hunted out.

Crises & Roman Persecution

Traditional histories of Christianity (as well as Catholic litanies) list thousands of Christian martyrs. There is little historical evidence for this claim; over the course of 300 years, we only have evidence for persecution perhaps seven or eight times, and usually only in the provinces. Even then, we only have a handful of names. This is because persecution was directly related to a crisis. Famine, drought, earthquakes, plagues, and invading armies were interpreted as the anger of the gods. For the most part, Christians were tolerated. It is only in the periods of crisis that scapegoats had to be found; it was those Christians who angered the gods. Everyone knew where the Christians lived - in crowded tenements and cities - they were noticeable for staying home during the numerous religious festivals, and during a period of crisis, they were easily arrested.

The two greatest periods of persecution were during the reigns of Decius (r. 249-251 CE) and Diocletian (r. 284-305 CE). In 250 CE, the Empire suffered a plethora of disasters - inflation, famine, invading armies, and a plague. Decius issued an edict that everyone in the Empire had to attend the imperial temples and appease the gods. In addition, people needed a receipt proving that they had been there. A black market of receipts flourished as Christians refused this edict.

After the reign of Decius, persecution ceased for a while. However, the Crisis of the Third Century brought economic and military instability. In constant competition for the throne, out of 25 subsequent "barracks emperors", only three died in their bed. In these short durations of power, a few took the bold step of legalizing Christianity, solely to recruit them into the Roman army. We know some Christians joined the legions, but most of them sat it out. As the traditional magistrates and patrons of the cities were away at war, Christians took over the traditional benefices of the cities. Through their charity of food and clothing and their early hospitals, these Christians became popular with the masses.

In 284 CE, Diocletian set about setting restoring the Empire. In 302 CE during one of the sacrifices, a priest discovered horrible entrails in the animals. Diocletian blamed the Christians, ordered their arrests, and also ordered them to burn their sacred scriptures. This became known as 'The Great (and Last) Persecution.' Upon Diocletian's unprecedented retirement, various individuals fought over Imperial power. In the West, Constantine I (r. 306-337 CE) successfully defeated Maxentius at the Milvian Bridge in Rome. He later claimed that he won the battle because of the Christian god and became a Christian. The Edict of Milan was issued in 313 CE, making Christianity a legal religion throughout the Roman Empire.

The Arenas

Rome did not have an established institution for convicted felons; there were no set periods of detention or a life sentence. Each city had holding cells for convicted prisoners until the next magistrate was available, and punishment was based upon class. The higher classes on a charge of murder or treason suffered decapitation, the lower-class criminals were executed in the arenas, which were tools of propaganda, providing public demonstrations of Roman law and order.

The venatio, (led by bestiarii, 'beast men'), was a form of entertainment. Rome literally converted arenas with sand and palm trees, and the bestiarii would re-enact the capture of wild animals such as lions, panthers, bears. The animals were also utilized as state executioners. Some convicts were forced to participate in the hunts, but most often they were tied to a stake and then mauled by the animal.

Contrary to popular belief, gladiators did not fight Christians in the arenas. The gladiator games were funeral games that originated with the indigenous Etruscan civilization. Two slaves fought to the death, and the loser accompanied his master in the afterlife. Rome developed this idea into an industry with gladiator schools. Gladiators sometimes fought to the death in a special funeral honor, a munera, but this was rare. Training gladiators was expensive, and no one wasted them on common criminals. Besides, in a sense of good sportsmanship, a gladiator against an untrained convict was a poor showing.

The Critics

Unfortunately, the literature of the ancient world comes from upper-class, educated men, and we have no idea what the average, lower-class Greeks or Romans thought of the new movement. Among the educated elite, however, there was criticism of Christians. Two 2nd-century CE philosophers, who read Christian scriptures and interviewed Christians, wrote treatises against the movement. Celsus in The True Word portrayed Jesus as an ordinary trickster, using magic to sway the crowds and warned that Christians were dangerous because they taught an alternative lifestyle that upended traditional social and religious conventions.

Galen, a 2nd-century CE physician who served the imperial household, had much praise for the healthy Christian practices (moderation in food and drink and curbing of the sexual appetite), but he also criticized their logic, particularly in the Genesis creation story. Galen claimed that it was impossible to create if there was no prior matter. (Hence the later Christian doctrine against Galen known as "creatio ex nihilo" or "creation out of nothing".) Beginning in the 2nd century CE and beyond, Christian bishops wrote responses to such criticism which ultimately became Christian theology.

Another text, known as Octavius by Minucius Felix (c. 197 CE), is often misunderstood as a standard polemic against Christianity. It is a dialogue between two friends, discussing what people think about Christians. This contains the now-infamous charge that Christian initiation involved the candidate killing a non-Christian baby disguised in flour and at the end of the ceremony, trained dogs pulled down the lamps and everyone groped their nearest neighbor in an orgy of sex. This text, however, was written by a Christian, most likely as satire.

The Concept of Martyrdom & the Cult of the Saints

In 167 BCE, the Jews rebelled against the Greek rule of Antiochus Epiphanes who had outlawed Jewish customs. In 2 Maccabees, as the victims were tortured, they made final speeches. They willingly sacrificed their lives because God "will raise them up" ('anatasis' in Greek, 'resurrection' in English), and the term 'martyr' was introduced (meaning 'witness' in Greek). The reward for martyrdom was instant translation to the presence of God in heaven. Christians adopted this concept for everyone who died for their faith.

Over the centuries, martyrologies appeared, stories of the suffering and death of the martyrs. The template was drawn from the passion of Christ the ordeals of Jesus. The Roman government supplied no services in the holding cells, which were damp, dark, and full of rats. Hunger brought on physiological changes to the body, and the prisoner spent the time reflecting upon upcoming death, giving rise to visions. Many of the visions functioned as valid ways in which to settle contemporary disputes in the communities. Further, the martyrologies also provided details of the miracles of these martyrs. There are stories of mutilations of limbs that grow back, sight being restored after blinding, and stories of virgin martyrs who should have been raped before execution because Roman law forbade the execution of a virgin. In these stories, the guards could not perform so that the victim remained intact going to her death.

After the conversion of Constantine, there were limited opportunities for traditional martyrdom. With Christianity now as a legal religion, they began to build churches and took over the municipal basilicas, originally civic halls. In the 380s CE, the bishop of Milan, Ambrose, solved the problem of making these sacred spaces by digging up the skeletons of two older, soldier martyrs and placing them literally in the walls of his new church. This period begins the rise of the cult of the saints. Borrowing the concept of patron gods and heroes, martyrs' tombs became intersections of heaven and earth. Pilgrims traveled to pray for intercession on their part, based on the same concept as the patron/client relationship, creating the patron saints of Catholic tradition.

An innovation to this system was the worship of relics. The bones (and various body parts) were now deemed sacred, holy objects that could facilitate miracle cures. This innovation again shocked both Jews and Gentiles as violating the concept of corpse contamination. Nevertheless, the trade of relics (most of them forgeries) became so outrageous in the Middle Ages, that it was eliminated by Martin Luther's reforms against the Vatican during the Protestant Reformation.

Conclusion

The growth of Christianity and its eventual triumph in medieval Europe is currently a major topic of interest for historians. The traditional view was that Christianity offered a system of morality and solace to a world that was spiritually bereft. This is patently not true; the ancients were just as pious and spiritually awakened as Christians. Christianity absorbed this culture but added unique innovations that provided new meaning, and in a world with no certainty of the afterlife, Christianity provided assurance of one in heaven. When Constantine the Great converted, how many saw the winds of political change as a practical way to survive and get ahead?