The Völuspá (Old Norse: Vǫluspá) is a medieval poem of the Poetic Edda that describes how the world might have come into shape and would end according to Norse mythology. The story of about 60 stanzas is told by a seeress or völva (Old Norse: vǫlva, also called spákona, foretelling woman) summoned by the god Odin, master of magic and knowledge. According to this literary text, the beginning of the world was characterized by nothingness until the gods created the nine realms of Norse cosmology, somehow linked by the World Tree, Yggdrasil.

At the same time, the fate of everything was set in stone by a group of seeresses. In the very beginning, two families of gods were involved in a war, ending with a truce and a wall around their divine citadel of Asgard. However, they would not live in peace forever because the universe has been doomed since the very moment of its creation. Every god has a specific enemy with whom they will do battle and many will be slain, including the chief god Odin.

Context

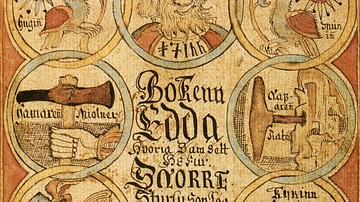

The Northmen of the 8th or 9th century CE whom we usually call Vikings did not really have any written sources for their religion. They carved some images in stone, they made some wooden idols, and they rather recited poems about what they thought the world was like. A few centuries after the age of these daring seamen, traders, and explorers, some Icelanders wrote down such poems remembered from ancestors. This collection of poems is called the Edda, and it is our most precious source of information about what the myths of the Northmen might have looked like.

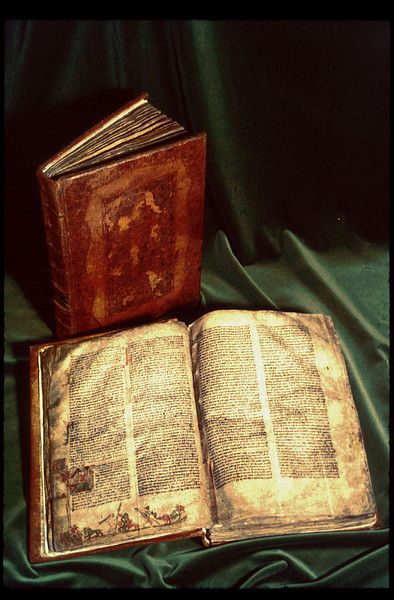

It is written in Old Norse, the language people used to speak in Iceland, Norway, Sweden, and Denmark up until the 15th century CE. These poems are found in two manuscripts, the Codex Regius (King’s book) and another book called the Hauksbók, but the order of the stanzas, the groups of four lines making up the poems, seems more logical in the first book. The first poem of the collection is the Völuspá, meaning the prophecy of the völva. Snorri Sturluson, a 13th-century CE Icelandic scholar, also wrote a version of these tales, quoting much of the poems in his book. The version he knew, however, seems different, indicating that the poems of the Edda were very popular among the Vikings.

How the World Began

According to the Völuspá, Odin, the leader of the Æsir gods, as the most important and mightiest family was called, was always eager for knowledge. He asks a völva, an ancient seeress, to rise from the grave and tell him, the father of the slain (Valfǫþr) – because he takes warriors into his famous hall of Valhalla) – stories of the past. She answers him by mentioning the nine worlds that make up the universe and the ash-tree Yggdrasil, as well as Ymir, a giant out of whose limbs the universe was made. There was "a yawning gap" at the beginning of time (Hildebrand, stanza 3). The creation of the universe seems to have been the work of the sons of Borr: Odin and his brothers Vili and Vé, whose names we know from another poem called the Lokasenna. The three brothers shape the earth, take their assembly seats, and then name the stars in the skies, thus giving an order to the universe. The gods meet at Ithavoll, a mysterious place only mentioned twice in the poem, where they set forges and make tools and set up temples.

At their dwelling, three giant-maids arrive, a possible reference to the Norns. The Norns were creatures even more powerful than the gods since they decided the fate of everyone. A council is held during which we are given a catalogue of the race of dwarves; very few of them are mentioned elsewhere. One of them, Gandalf, was turned into a wizard by Tolkien in The Lord of the Rings. Another one, Dvalin, is important, too, since he seems to have given the dwarves magic runes which made them very skillful, as told in the second poem of the Edda, the Hávamál. Then we have Andvari, the one who tells in a poem called Reginsmál about how Loki, the trickster god, stole his wealth, causing him to curse the treasure that brought the death of Sigurd. Sigurd is the tragic legendary hero who killed a dragon with a cursed treasure, inspiring many authors among whom, once again, Tolkien. After this section with the many dwarves, three gods, Odin, Hönir, and Lothur, continue their work and create mankind out of two trees, ash and elm (Ask and Embla). The fates reappear in stanza 20, where they carved runes on wood and made laws.

The prophetess then tells what she remembers as the first war in the world, between the godly families of the Æsir and the Vanir. The latter is rather linked to fertility and prosperity, although it must be said that Norse gods, in general, cannot be limited to well-defined characteristics. Either way, the story in the Völuspá mentions the goddess Gollveig (gold-might) as a reason for the war, as she was accused of bewitching the gods. The outcome of this war was that all gods received equal right to worship, possibly an allusion to the acceptance of other regional deities into their system of beliefs.

In a sudden change of topic, we then get a glimpse of other major mythical events, such as the rebuilding of Asgard, the fortress of Odin and his family, and possibly one of the nine worlds the prophetess was speaking of. When the giant assigned the task demands the love goddess Freyja as a reward, Loki is requested to play a trick on him to prevent this from happening. As expected, the giant ends up slain by Thor, the mightiest of the gods, which infuriates the giants who eagerly battle the Æsir. The giants were in fact another family of gods - their name does not refer to their size - and many were romantically involved with the gods of the Æsir family.

The End of the World

"Would you yet know more?" (Hildebrand, stanzas 27, 29, 34, 35, 39, 41, 48, 62) This question pops up periodically, reminding us that Odin is the god who always seeks to gain knowledge. The horn of Heimdall, which will announce the final battle, is hidden under the holy tree, where we find another curious object, namely Odin's eye. He sacrificed his eye to the spirit Mímir to gain more wisdom. It seems as if it was then used as a drinking vessel. After being rewarded by the god with rings and necklaces, the völva continues with the real prophecy of the poem. She sees valkyries assemble, so as to join the ranks of the gods for the final battle. Valkyries are the female warriors assigned by Odin to pick up dead brave fighters from the battlefield and take them to Odin. Their name actually means the choosers of the slain.

Before this great event where fates are to be fulfilled, we are reminded of the catastrophe which was Baldr's death, the beloved, fair and innocent son of Odin and Frigg. More details on this are to be found in a particular poem, Baldrs Draumar. Frigg demanded that all creatures swear not to harm Baldr, which they all did, except for the mistletoe, hurled by Baldr’s blind brother under the guidance of Loki. After Baldr got killed with the arrow made out of mistletoe, Loki was punished, and we have a more complete image of his punishment in the Hauksbók manuscript: he was bound to a rock with the bowels of his son Narfi, mauled by his other son Vali, with a serpent dripping poison on him and his loyal wife attempting to collect it in a bowl.

After describing the homes of the frightening enemies of the gods, not only giants and dwarves but also the wicked dead from Hel's realm Nastrond (corpse-strand), the völva warns of another sign of destruction, the stealing of the moon. It would not be wrong to understand this as an eclipse. The final battle is announced by the two apocalyptic roosters: Fjalar and Gollinkambi. Perhaps one of the ultimate signs of the impending doom would be the escape of Fenrir the wolf, the one kept in chains by the sacrifice of the god Tyr, who willingly let him bite off his hand. Dark times will come, "wind-age, wolf-age / soon the world shall fall / not even men / shall spare each other" (Hildebrand, stanza 45). Odin, no matter how much wisdom he has gathered, will still be slain by Fenrir. Yggdrasil is shaking.

The name 'ragna røk', Ragnarök, used to describe this major event, can be translated as the fate of the gods and is found in stanza 50. Other elements of chaos include Hrym, the leader of the giants, the sea-serpent encircling the world, Midgardsorm, and the terrifying ship made of dead men's nails, Naglfar. The giant Surt brings fire from the south and fights the god of prosperity Freyr, whereas Odin fulfills his fate in front of his misfortunate wife Frigg. Thor, son of Odin and the earth, is also destined to fall in this great battle, against the sea-serpent that will kill him with its venomous breath. The apocalypse gains momentum after the episode involving the most popular of the gods, as "the sun turns black / the earth sinks in the sea / hot stars are whirled down / from heaven" (Hildebrand, stanza 57).

Conclusion

Is this truly the end? With humanity lost and the gods defeated? No, according to the poem the world will rise again, because there are still a few gods remaining and they gather and talk about the recent events and the fall of the master of runes, Odin. His son Baldr returns, the fields are once more filled with ripe fruit, the nephews of Odin dwell in heaven. On the mountain Gimle, one can see a great golden hall with a mighty unnamed ruler.

It seems like quite an intense story, but like many other aspects of Norse mythology, many pieces are missing from the puzzle and it has been suggested many times that Christianity might have influenced the last part of the poem. While this is difficult to sort out, the poet was more probably heathen, as suggested by the tone, the images, archaic language features, and style of the poetry. It must also be said that a lot of the Norse creation and destruction myth also living in popular culture nowadays actually comes from Snorri’s interpretation, who turns all those hints in the poem into a much more coherent story.

The original poem, the Völuspá, might seem quite mysterious to both us and late medieval Icelanders, but not to the people it was intended for. On the other hand, it has a unity lacking in many of the other poems, casting a shadow of a doubt whether the myths presented are indeed authentic or whether the author embellished them or added his own thoughts. After all, mythology by its nature is subject to creative reinterpretations. The Northmen themselves probably imagined their major mythical events in different ways than we do today. It is uncertain whether they were indeed thinking of a rebirth after that destructive final event, the Ragnarök. The story of their universe goes in one clear direction, and no one could do anything to prevent the destruction. What was there left to do? Fight with dignity until the very end.