The megalithic temples of Malta and Gozo rank amongst the oldest free-standing buildings in the world. Construction of these temples started c. 3500 BCE, an impressive architectural feat for their time, particularly given that the builders had limited access to materials and did not have metal tools at their disposal. Though we do not know much about how these people lived before their disappearance in 2500 BCE, the temples they left behind can tell us a lot about the progression of their art style and even start to give us a picture of their religious practices.

The Early Neolithic Period

The Early Neolithic Period on Malta can be split up into three distinct phases:

- Għar Dalam Phase - 5200-4500 BCE

- Grey Skorba Phase - 4500-4400 BCE

- Red Skorba Phase - 4400-4100 BCE

The first phase was named after the Għar Dalam Cave, which was discovered on a dig of the Skorba sites near Mġarr on behalf of the National Museum of Malta from 1961-1963 CE. The site, containing human and animal remains, fragments of pottery, stone tools, and other artefacts, was found underneath two later temples - one from the Ġgantija Phase, which was reused and altered in the Tarxien Phase, and the other built in the Tarxien Phase. The Għar Dalam pottery found at the site was notably similar to the Stentinello impressed ware pottery found in Sicily, which supports the widely accepted belief that the first inhabitants of Malta came by boat from Sicily.

After radiocarbon dating analysis of the pottery fragments was undertaken, it was determined that some of the finds were created later than first thought and, to accommodate this, the Grey Skorba Phase and the Red Skorba Phase were officially recognised. The Grey Skorba Phase is characterised by the use of dark grey clay with the addition of white particles in the making of this pottery, whereas, in the Red Skorba Phase, we see the addition of red slip (a mixture of clay and water) being used to coat the pottery, though the white particles still remain.

The evidence we have suggests that the first settlers on Malta were a community of farmers. The discovery of two sickle blades, which can be dated to the Grey Skorba Phase, the bones of domesticated animals, and the remains of wheat and barley all point towards farming. Though, carved limestone rocks which would have likely been used as slingshot ammunition show that it is likely this community also practised hunting. The pebble and earthen floor of a single-story oval-shaped house was found, and evidence of similar domestic settings is also found on the nearby island of Gozo, namely the remains of a village at Santa Verna. Figurines depicting women and dating to the Red Skorba Phase were also found.

The Temple Period

Across the islands of Malta and Gozo, there are seven megalithic temples, a number of which are recognised as UNESCO World Heritage Sites. The Temple Period of Malta is split up into five phases:

- Żebbuġ Phase (4100-3800 BCE)

- Mġarr Phase (3800-3600 BCE)

- Ġgantija Phase (3600-3200 BCE)

- Saflieni Phase (3300-3000 BCE)

- Tarxien Phase (3000-2500 BCE)

Though the Żebbuġ Phase starts c. 4100 BCE, no temples were built until c. 3500 BCE. The Żebbuġ Phase was characterised by the development of rock-cut tombs such as the tombs found at Xemxija by John Davies Evans in the 1950s CE.

The Żebbuġ & Mġarr Phases

The Żebbuġ Phase marks the transition from rock-cut tombs, standing stones, and small shrines to the impressive temples documented in the later phases of temple building. The better-known finds from this period are found at the Ta' Trapna tombs near Żebbuġ in Malta, which were first found in 1947 CE by workmen digging to lay building foundations. These five tombs contained human remains, ornaments of bone and seashell, pottery fragments, and lots of evidence of red ochre paint. The Żebbuġ pottery discovered at the site is characterised by the incised lines used to decorate it - sometimes these incisions were depicting humans, but they were mostly of semicircles, triangles, and other simple shapes. Most of the pottery from these tombs was found in fragments, with only one vessel discovered complete. These were made of grey clay with white chips, similar to the pottery of the Grey Skorba period, but with a polished slip coating. Similar finds were found at the Xagħra Stone Circle.

The Mġarr Phase is a shorter transitional phase just before the first temples were built in the Ġgantija Phase. Unlike the incised lines of the Żebbuġ Phase, the pottery of the Mġarr phase is characterised by curved lines, though the use of red ochre in the decoration of these artefacts is still widely used. Most of the pottery dating from this period was found at the Ta' Ħaġrat temples in Mġarr (Malta) and the fact the pottery pre-dates the temples themselves suggests that a village stood at the site before the building of the temples took place. The major Ta' Ħaġrat temple was built during the Ġgantija Phase and the minor one was built during the Saflieni Phase.

The Ġgantija Phase

The oldest temples in Malta can be dated to the Ġgantija Phase. The best-known temple site from this period is the Ġgantija Temples on the Xagħra Plateau, Gozo. There was extensive restoration work done on the temples in the 2000s CE, and in 2013 CE the complex was opened as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The biggest, oldest, and best-preserved of the two temples that make up the Ġgantija complex is the South Temple, built c. 3600 BCE.

Generally, the architectural structure of these megalithic temples was that of an oval forecourt, which led onto a corridor made up of trilithons (two stone slabs supporting a third on top). This corridor then led onto an open space with apses built off the sides. The number of apses varied; if there were many, a second trilithon passage was built to accommodate them. This is the case in the South Temple whose five apses are separated by a second corridor - there are two apses after the first corridor and three after the second. Discoveries of altars and animal remains suggest that the site was used for rituals likely involving animal sacrifices. Other impressive artefacts include a fragment of a beautiful bowl with a repeated pattern of birds incised into it and jewellery in the form of beads, pendants, and buttons made of stone, bone, and seashells.

Another temple of note from the Gganija phase is the main temple of the Ħaġar Qim site on Malta. First uncovered in 1839 CE by J. G Vance and then excavated further by Themistocles Zammit in 1909 CE, this temple has a paved central area of smooth stone slabs leading onto an original four apses, though more rooms were added later on in the temple’s construction. As suggested by the archaeologist David H. Trump, the right apse was likely used as an enclosure for sacrificial animals, and the animal bones discovered at the site also point towards animal sacrifice being a likely use for the temple. Similarly to the Ġgantija complex, altars were also found at the Ħaġar Qim temple - most striking of all being the one discovered close to the trilithon entrance with plant decoration in relief. The northern temple of the Ħaġar Qim complex is much older than the main temple and has five apses.

The Saflieni Phase

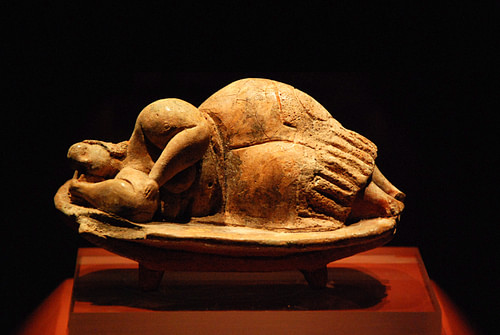

The Saflieni Phase takes its name from the intricate underground burial complexes of the Ħal Saflieni Hypogeum, the biggest hypogeum in Malta, made up of three levels cut into a limestone hill. The first level of the temple is composed of burial chambers cut into the side of a crater made at the top of the hill. The middle and lowest levels were then built down into the hill over time, with the lowest level being 10.6 metres (35 ft) below today’s ground level. Found at this site were the remains of approximately 7000 individuals, with some of the bones being lavishly covered in red ochre. This practice suggests a burial ritual where the mourners painted the bones red to symbolise the blood of life The dead were buried together with some personal belongings and offerings including pendants and painted pottery, as well as figurines of so-called ‘fat-ladies’ and animals.

The decoration inside the hypogeum is that of wall paintings of spirals and honeycomb designs in the same red ochre paint found on the bones. A small nook in the wall was also found that creates echoes, which would have been powerful and haunting background noise to the burial rites. Some of the doorways are made to look like the trilithon entrances found in the temples above ground, showing that the hypogeum may have had a religious significance.

The minor temple from the Ta' Ħaġrat complex is also dated to the Saflieni phase. This 6.5-metre (21 ft) long temple is much smaller than the temple from the Ġgantija Phase and is built using smaller stones. The temple can be entered from the eastern apse of the major temple and contains an oracle apse as part of its design.

The Tarxien Phase

The Tarxien Phase marks the golden age of temple building on Malta and is characterised by intricate decoration, including spiral designs, and well-polished pottery. The most impressive temple complex is the Tarxien Temples themselves. This group of four temples, which is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, was discovered in 1913 CE by a local farmer before being excavated by Sir Themistocles Zammit in the following few years. The site was then restored in 1956 CE. Three out of the four temples found at Tarxien are dated to the Tarxien Phase (3000-2500 BCE) and the fourth one, which is in worse condition, can be dated to the Ġgantija Phase. The architectural structure of these temples is the same as the apse design used in the Ġgantija temples, though the Central Tarxien Temple is unique in its six-apse plan; four of these apses are placed after the first corridor and another two are separated by a second corridor.

The discovery of altars and carvings of animals onto the stone walls of the Tarxien temples suggest that, like at the Ġgantija temple complex, animal sacrifice was one of the uses for these temples. Famously, a relief depicting a bull and sow can be found in a chamber between the Central and South Temples. Arguably the most impressive artefacts of the Tarxien temple site were discovered in the South Temple, including a huge 'mother goddess' statue with a pleated skirt, which was found just outside it. Inside the temple, a stone slab depicting a procession of 22 goats is among several reliefs of animals found in the third apse.

The statues, figurines, reliefs all attest to impressive artistic ability, however, what is perhaps most interesting of all is what the Tarxien Temples can tell us about the construction of the megalithic temples on Malta and Gozo. The discovery of stone spheres found outside the South Temple suggests that, in the absence of the wheel, which had not yet been invented, the builders of these temples moved the huge, limestone slabs by rolling them on these spheres. Stone spheres of this nature were also found alongside the northern temple of the Ħaġar Qim complex, suggesting that this technique was used throughout the temple building phases.

The south temple of the Mnajdra complex, built in the early Tarxien Phase, is another stunning show of the technology the prehistoric population of Malta may have put to use. Lying close to the Ħaġar Qim site, these temples were first excavated by J. G. Vance in 1840 CE before further work to discover new material was undertaken in the 1900s CE, notably by Dr Thomas Ashby in 1910 CE. The south temple, which has a two trilithon passage design, is astronomically aligned. The second passageway and the two megaliths on either side of it are illuminated by sunlight on the equinoxes and solstices. Whether this alignment was purposeful or not is something we can never be sure of given the lack of written evidence, although research done by scholars such as Frank Ventura and George Agius suggests that it may be. The south temple of the Mnajdra site shares an oval forecourt with two other temples, one built much earlier in the Ġgantija Phase and the other built later on in the Tarxien Phase.