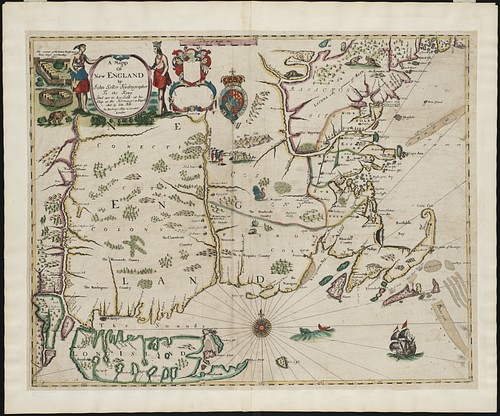

King Philip's War (1675-1678) was the pivotal engagement between the second generation of English immigrants who had arrived in New England and the Native American tribes of the region. The English won the war, and the natives lost not only their land but, in many cases, also their language and culture, at least for a time.

The policies of both sides were informed by earlier Anglo-Native conflicts including the Indian Massacre of 1622 which resulted in 347 English colonists killed by the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy in Virginia, the later Third Powhatan War (1644-1646) which killed over 500 colonists in the same region, and the Pequot War (1636-1638) during which the Pequot tribe sought to enlist the Narragansett in the same sort of operation against the English.

The conflict was begun by Metacom (also known as King Philip and Metacomet, l. 1638-1676), chief of the Wampanoag Confederacy, in response to the policies of Plymouth governor Josiah Winslow (l. c. 1628-1680), which encouraged colonial expansion into Native American territory, and colonial usurpation of Native American rights concerning justice. Metacom's father, Massasoit (l. c. 1581-1661), had signed the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty with the first governor of Plymouth Colony, John Carver (l. 1584-1621), on 22 March 1621 which promised mutual aid and protection as well as the right of each party to punish their own for crimes. When the colonists hanged three high-level Wampanoags for murder in June of 1675, Metacom, tired of English lies, broken promises, and land theft, launched his first offensive.

The war devastated the region, destroying English and Native American settlements equally, costing thousands of lives, disrupting trade, and destroying crops. When the English finally could declare victory in 1678, the political, social, and demographic make-up of New England was completely changed. After Metacom was killed in 1676, the Native American initiative flagged and after 1678 those natives who had fought for Metacom's cause – as well as many who did not – were sold into slavery, deported, pushed onto reservations, or absorbed into other tribes. The war was hailed as a great victory for 'God’s People' against the 'heathen' but, actually, it was the inevitable result of English greed and Native American naivete and lack of unity.

Causes of the War

The causes of the war go back to the founding of Plymouth Colony in November 1620. The passengers of the Mayflower found the village of Pawtuxet abandoned - because the inhabitants had all died of European-borne diseases carried by traders c. 1610 - and settled there without ever compensating the tribes of the Wampanoag Confederacy who still used the land. This same model was observed with the establishment of Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1628 and again in 1630. Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683), an English theologian who lived at both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, criticized this policy c. 1633, noting that King James I of England had no right to claim foreign lands already inhabited and his subjects had even less right to settle those lands without compensating the owners fairly.

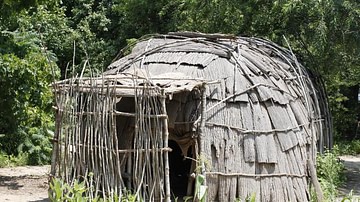

Williams was exiled from Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1636 for his religious views which differed from those of the magistrates, but his arguments concerning land rights of Native Americans certainly did nothing to endear him to the authorities. The colonists continued to take land from the natives, sometimes by way of what they saw as legitimate transactions and sometimes by outright theft. The natives did not fence in their territories because they did not believe they owned the land. In the same way, transactions of valuables for land were understood by the natives as gratuities for use of the land, not as a sale.

The immediate cause of the war was the death of the Wampanoag chief Wamsutta (l. c. 1634-1662) who was succeeded by his younger brother Metacom (King Philip), and the hanging of three Wampanoags, all high-level counselors to Metacom, by the colonists. Wamsutta had died shortly after returning from a meeting with Josiah Winslow at Plymouth, and Metacom claimed he had been poisoned. His claim was most likely true because Winslow had no regard for the natives and saw them as obstacles to progress that should be removed. Even though Metacom did not move against the colonists at this time, Wamsutta's death seems to mark a cooling of relations between the natives and the English.

Between Wamsutta's death in 1662 and the outbreak of hostilities in 1675, the colonists took more land in breach of the Pilgrim-Wampanoag Peace Treaty of 1621. The colonists had been welcomed to the land they had already claimed by the coast, but, increasingly, they were settling further and further inland. Metacom had repeatedly tried to negotiate with both Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay to stop expansion, but the English promises were never kept as they would have hampered profitable land deals made by men like Winslow.

Metacom began discussing an attack on the colonies with chiefs of his tributary tribes and others and news of this was brought to the colonists by one John Sossamon who overheard the talks. Sossamon was a former counselor and interpreter of Metacom's who had left to live with the English. He was a so-called 'praying Indian' – one who had converted to Christianity, learned English, and adopted English culture and dress. The praying Indian often served as interpreter in land deals and negotiations and so passed relatively freely between native and English villages. Sossamon’s report resulted in a call from the colonists for Metacom to explain himself - which he did, denying the truth of Sossamon’s account - but only after Sossamon was found dead.

Two months later, although many people had been interrogated and none had any information on the murder, eyewitnesses were suddenly produced by Winslow, and three Wampanoags were charged with Sossamon's murder. On 8 June 1675, these men were hanged by the English in direct breach of the 1621 treaty which made clear that each party would be responsible for punishing their own. Three days after the hanging, the Wampanoags were arming themselves outside Swansea Colony, and the first attack was launched against Swansea on 24 June 1675, starting the war.

Timeline of the War

The timeline of King Philip's War is well documented by colonial writers although some accounts seem to repeat the same information. The following timeline is constructed from a number of works but relies primarily on scholar Jill Lepore's The Name of War: King Philip's War and the Origins of American Identity, xxv-xxviii:

1675:

- 29 January: John Sossamon killed

- 8 June: Sossamon's alleged killers are hanged at Plymouth Colony

- 11 June: Wampanoags are in arms at Swansea Colony

- 14-25 June: Rhode Island, Plymouth, and Massachusetts Bay colonies attempt negotiations with Metacom and other chiefs

- 24 June: Wampanoag Confederacy attacks Swansea

- 26 June: Massachusetts Bay militia join Plymouth Colony militia in defense of Swansea

- 26-29 June: Wampanoags attack Rehoboth and Taunton; Mohegans go to Boston with an offer to fight for the English

- July 8-9: Wampanoags attack Middleborough and Dartmouth

- July 14: Nipmuck tribe attacks Mendon

- July 15: Narragansetts sign a peace treaty with Connecticut colonies

- July 16-24: Massachusetts envoys attempt to negotiate with the Nipmuck tribe

- July 19: Metacom and his army escape to Nipmuck territory

- August 2-4: Siege of Brookfield - Nipmucks attack Massachusetts troops and besiege Brookfield

- August 13: Massachusetts Council orders Christian Indians confined to praying towns

- August 22: Native American warriors kill seven colonists at Lancaster

- August 30: Captain Samuel Moseley arrests 15 Hassanemesit tribal members for Lancaster assault and marches them to Boston

- September 1-2: Wampanoags and Nipmuck attack Deerfield. Massachusetts forces led by Moseley attack the village of Pennacook

- September 12: Battle of Bloody Brook – 57 out of a 79-man company killed; colonists abandon Deerfield, Squakeag, and Brookfield

- September 18: Narragansetts sign a peace treaty with the English in Boston while Massachusetts troops are ambushed near Northampton

- October 5: Pocumtucks attack and destroy Springfield

- October 13: Massachusetts Council orders Christian Indians removed to Deer Island

- 19 October: English repel an attack from Indians from Hatfield

- 1 November: Nipmucks take Christian Indians captive at various points

- 2-12 November: Commissioners of the United Colonies order an army to attack the Narragansetts.

- 7 December: Massachusetts Council issues a broadside explaining the case against the Narragansetts

- 19 December: The Great Swamp Fight - Colonial forces attack the Narragansett stronghold in the Battle of the Great Swamp; over 600 Narragansett killed as well as women and children of other tribes

1676:

- c. 1-14 January: Metacom leads his people to New York seeking help from the Mohawks; Mohawks side with the English and attack him, driving him back to New England

- 27 January: Narragansetts attack Pawtuxet (area of Plymouth Colony)

- 10 February: Lancaster Raid - Nipmucks attack Lancaster settlement; Mary Rowlandson taken captive

- 14 February: Metacom and his tribe attack Northampton, MA; council debates erecting a wall around Boston

- 21 February: Nipmucks attack Medfield

- 23 February: Indian assaults within ten miles of Boston

- 1 March: Nipmucks attack Groton

- 26 March: Settlements of Longmeadow, Marlborough, and Simsbury attacked

- 27 March: Nipmucks attack Sudbury settlement

- 28 March: Indian bands attack Rehoboth

- 20 March: Providence Colony is destroyed

- 21 April: Sudbury Fight - Indian bands attack Sudbury settlement, killing half the militia

- 2-3 May: Mary Rowlandson is released and returns to Boston

- 18 May: Battle of Turner’s Falls - English forces attack sleeping Indians near Deerfield; 200 Native Americans killed in revenge for Battle of Bloody Brook

- 30 May: Indians attack Hatfield

- 31 May: Christian Indians are moved from Deer Island to Cambridge

- 12 June: Indians attack Hadley settlement but are repelled

- 19 June: Massachusetts issues a declaration of amnesty for Indians who surrender

- 2 July: Second Battle of Nipsachuck – colonial victory; Major John Talcott and his troops begin sweeping Connecticut and Rhode Island, capturing large numbers of Algonquians who are transported out of the colonies as slaves throughout the summer

- 4 July: Captain Benjamin Church and his soldiers begin sweeping Plymouth for Wampanoags

- 11 July: Indians attack Taunton but are repelled

- 27 July: Nearly 200 Nipmucks surrender in Boston

- 2 July: Benjamin Church captures Metacom's wife and son

- 12 July: Battle of Mount Hope - John Alderman, an Indian solder under Church's command, kills Metacom/King Philip.

1677-1678: Northern and Southern tribes continue the war without Metacom's leadership, finally surrendering in 1678. The war is concluded by the Treaty of Casco of 1678.

Pivotal Battles & Events

Every engagement of King Philip's War was brutal, hand-to-hand combat or massacre on both sides, but a number of these are considered pivotal in that they directly resulted in another episode of carnage or significant step in the war.

Battle of Bloody Brook, 12 September 1675: Metacom observed a company of approximately 79 men gathering crops in the fields for transport to a nearby colony. He had his men cut down trees to block the road the company would have to take, and the convoy of wagons was stopped. The English left their weapons in the wagons to move the logs from the path, and those not engaged with clearing the road went foraging for food. The Wampanoags fell on the group, killing 57 of the 79. This massacre was cited as justification for the campaign against the Narragansetts known as the Great Swamp Fight as well as the later massacre of Native Americans known as Battle of Turner’s Falls on 18 May 1676.

The Great Swamp Fight, 19 December 1675: The Narragansett tribe had remained neutral when hostilities broke out. They had allied with the English against the Pequot tribe during the Pequot War and been rewarded with land and trade agreements. They felt bound by honor, however, to accept the women and children, as well as the injured, from the Wampanoag and other tribes engaged in the conflict. Winslow claimed the Narragansetts were helping the enemy; they claimed they were only offering shelter to non-combatants. On 19 December 1675, a combined militia force from the colonies, led by Winslow, attacked the Narragansett stronghold near present-day South Kingstown, Rhode Island, killing over 600 Narragansett as well as the women, children, and injured of the other tribes. Most of the Narragansett warriors were away from the fort at the time. This event brought the Narragansett into the war on Metacom's side and cost the colonists dearly afterwards through Narragansett raids.

Metacom and the Mohawks, early January 1676: In an effort to bolster his forces, Metacom led his army to New York to seek assistance of the Mohawks. The Pequot chief Sassacus (l. c. 1560-1637) had tried this same tactic during the Pequot War, but the Mohawks killed him and sent his head and hands back to the English as a gesture of friendship. Metacom made out only slightly better than Sassacus in that he lived through the encounter after the Mohawks attacked him, killing many of his warriors, and drove him back to New England. Without assistance from the Iroquois Confederacy, Metacom was left to fight on his own with dwindling resources.

The Lancaster Raid, 10 February 1676: The Lancaster settlement was attacked by Narragansett, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag warriors, killing many and taking others captive. The raid is one of the most famous of the war due to the work of one of these captives, Mary Rowlandson (l. c. 1637-1711), who was later released and wrote the bestselling captivity narrative The Sovereignty and Goodness of God: Being a Narrative of the Captivity and Restoration of Mrs. Mary Rowlandson, which is considered a classic of colonial literature and reliable first-hand account of life in a Native American village.

The Sudbury Fight, 21 April 1676: After a native coalition destroyed the fortified settlement at Marlborough, Massachusetts, the Bay Colony sent one Captain Samuel Wadsworth and 50 militia to the area to protect survivors. Sudbury was destroyed and Wadsworth’s militia lost half their number in a well-coordinated attack by over 500 native warriors. This was the last Native American victory in the war. As with earlier engagements, the Sudbury Fight encouraged further engagements as the colonists sought revenge.

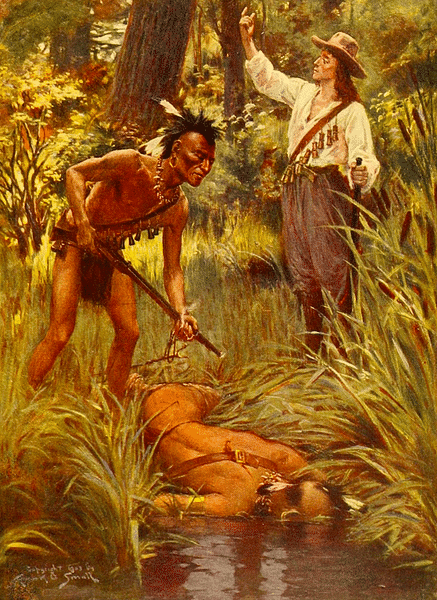

The Battle of Mount Hope, 12 August 1676: The militia under Captain Benjamin Church (l. c. 1639-1718) and Josiah Standish (l. c. 1633-1690), both of the Plymouth Colony, were led to Metacom’s camp on Mount Hope by a praying Indian named John Alderman, who had formerly been one of Metacom’s counselors before converting to Christianity. Alderman identified Metacom and shot him in the back, killing him. Church then gave Alderman the chief’s head and hands which, for a price, Alderman would show to others afterwards until he finally sold the head to Plymouth Colony for 30 shillings. Metacom’s death effectively ended the war although tribes continued to fight on to the north and south of the region until 1678.

There are many more pivotal moments in the war, as well as shifts in policies such as those regarding the praying Indians. Christian natives had always been trusted more than non-Christians, but the colonists would have had in the back of their minds the memory of the Indian Massacre of 1622 at Jamestown. In March of 1622, the Powhatan Confederacy launched a one-day attack on the settlements, killing 347 colonists, and this was preceded by natives feigning an interest in conversion in order to lower English defenses. Accordingly, during King Philip's War, no Native American was completely trusted and Christian natives were often treated quite poorly, first confined to their towns and cut off from their farms and food supply, and then approximately 1,000 relocated to Deer Island in October 1675 where many died of starvation and exposure.

Conclusion

As in the case of the Pequot War, King Philip's War was lost by the natives, in large part, due to a lack of unity and the persistent belief on the part of some factions that they would be treated better by the English than others. During the Pequot War, the Pequots had tried to win the Narragansetts to their side, but the Pequots and Narragansetts had traditionally been rivals, and the Narragansetts listened to the advice of Roger Williams and sided with the English, dooming the Pequots. The Mohegans in this war also sided with the English and for the same reason: because they did not believe that what happened to others at English hands would happen to them.

Both tribes were wrong and the Narragansetts, anyway, repeated the mistake in King Philip's War, remaining neutral for the first six months. If the Mohawk had decided to help Metacom instead of the English, they could have made a substantial difference in the war. Instead, they placed their trust in the English who, less than 100 years later, drove them from their New York lands into Canada and forced them to negotiate to get some of them back.

Conflicts would continue after King Philip's War as the English moved west and north, expanding into other territories, and Native Americans became involved in the French and Indian War (1754-1763), pitting tribes allied with the English against those fighting for the French. When the French lost the war, the English took their land south of the Canadian border and settled more colonists there. Native American tribes who had fought for the English, and hoped they would now be rewarded, were eventually betrayed just as the Narragansetts, Mohawks, and many others had been. The reservation system, established earlier, was developed more rapidly after King Philip's War, and native lands shrank along with Native American autonomy.