Life in Colonial America was difficult and often short but the colonists made the best of their situation in the hopes of a better life for themselves and their families. The early English colonists, used to purchasing what they needed, found they were now required to either import items from the mother country, make them, or do without.

Even later arrivals, unless of the upper class, found the New World challenging as most people had to work hard just to survive. At the same time that they were literally creating towns and cities from wilderness, they were contending with periodic attacks from Native American tribes who had been displaced and needed to also be on guard against robbers or even members of their own households (servants or slaves) who could do them harm.

On top of this were the very many supernatural threats to life and health concocted by the devil and his legion of evil spirits which could come at any moment as well as natural hazards such as various illnesses, poisonous plants, wild animal attacks, and the many dangers involved in simple home life; just cooking a daily meal could result in scalding from a cast-iron pot of stew, candle-lit homes of wood and thatch were apt to catch fire, and twine-bound ladders could break.

Even so, these challenges did not deter the thousands of English (not counting convicts, orphans, and others sent involuntarily) from leaving their homes and traveling to the New World in the hope of improving their lives. The strict social hierarchy of England, which almost always kept one in the social class one was born to, was significantly relaxed in the colonies, and a former servant, male or female, was offered the possibility of a much better life, even that of a landowner if they could survive. Between 1630-1640, over 20,000 colonists arrived, and even more followed, pursuing the American dream before the concept was even fully articulated.

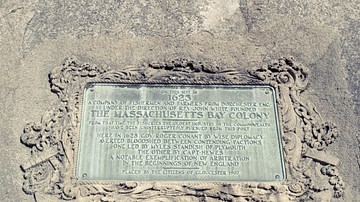

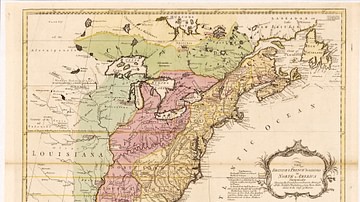

Jamestown was settled first in 1607, then Plymouth Colony in 1620, Massachusetts Bay in 1630, and so on. By 1763, the English had colonized the entire eastern seaboard of lower North America from modern-day Maine to Florida and these settlements were divided into three regions:

Virginia and Maryland, both Southern Colonies, were also known as Chesapeake Colonies. Although daily life in these regions differed owing to climate, the soil, and the kinds of dangers they presented, some fundamental beliefs and one’s daily life were relatively uniform throughout and, among them, was religion and a belief in the very real influence – for good or ill – of supernatural forces on one’s life.

Religion & Superstition

The colonists, whether the so-called pilgrims of Plymouth or the Anglicans of Jamestown, were deeply religious Christians who regarded the Bible as God’s Word and understood they were supposed to live their lives according to its strictures. Belief in the reality of a supernatural deity, angels, and evil spirits encouraged the development of extra-biblical superstitions which conformed to the Christian vision.

The Native Americans were almost instantly identified with dark forces. Even Edward Winslow (l. 1595-1655) of Plymouth Colony, who encouraged friendly relations with the natives, claimed they worshiped the devil. Natives were thought to be able to cast spells, wither crops, hurt or heal at will, by drawing on the power of evil spirits of the devil himself. Fellow colonists could also harness this power, however, and so had to be carefully watched. A woman who could walk the dusty roads of a New England town and arrive at her destination looking more or less as neat and clean as when she had left her home was suspected of being a witch just as a man who seemed unusually strong, productive, or profitable might be.

Conformity to the social norms was expected in every colony – even the liberal Providence Colony which welcomed people of all religions and nationalities or the Provinces of New York and Pennsylvania which did the same – and any aspect of a person’s life which seemed out of the ordinary warranted suspicion. The most famous example of this, of course, is the Salem Witch Trials of 1692-1693 in Massachusetts - which resulted in over 200 accused and 20 executed by hanging - but witchcraft was regarded as a palpable threat in all of the colonies, and witch trials were held before and long after the infamous Salem event. Although marginalized groups, mainly women, were the most frequent targets of accusation, anyone from any social class could be suspected or accused of consorting with the devil.

Social Classes

Although the social hierarchy was more relaxed in the colonies, it still existed and descended from top to bottom:

- Upper-class Landowners

- Merchants and Clerics

- Farmers, Artisans, & Laborers

- Indentured Servants

- Native Americans

- Slaves

People of different classes were identified by the clothing and accessories they could afford, and laws were passed in a number of colonies prohibiting those of lower classes from dressing as their social superiors; doing so warranted a fine or even time in the stocks. The upper class were the landed gentry who owned large plantations in the Southern Colonies or extensive landholdings/farms in the Middle and New England Colonies. Only upper-class, landowning white males over the age of 21 had the right to vote, serve in government, and make laws, although many well-to-do merchants or clerics were also allowed.

Merchants and clerics were next in the order, some of whom were also landowners. Clerics were not only scribes and lawyers but ministers, some of whom were quite wealthy while others struggled to survive. Teachers were also counted as clerics but, outside of New England, were not highly respected. The Puritans of New England placed great value on literacy, founding Harvard University and other institutions, because of their belief that everyone should be able to read the Bible, but few of the other colonies followed suit.

Farmers, artisans, and laborers were those who owned small farms, businesses (brewing, barrel-making, candle-making, dressmaking, shipwrights, etc.), or were skilled or unskilled workers. Below them were the indentured servants, people who had signed a contract to work for four to seven years for someone in return for passage to the colonies, food, and shelter. At the end of their service, they were given a parcel of land, tools, and a firearm. An indentured servant, at least in the early years of the colonies, could rise from the lower class to join the elite.

Native Americans were considered outsiders, and this was more or less true even for the so-called “praying Indians” – natives who had converted to Christianity, settled in towns close to English colonies, dressed in English clothing, and learned the English language. After the Indian Massacre of 1622 in Virginia, during which the tribes of the Powhatan Confederacy killed 347 colonists in Virginia in a surprise attack, natives were viewed with suspicion. The colonists, in fact, justified later atrocities committed against Native Americans by citing the 1622 massacre and the Anglo-Powhatan Wars which followed it.

Below the Native Americans were the African slaves (although many Native Americans were also enslaved). The first West Africans arrived in Virginia at Jamestown in 1619 but, at first, were treated more like indentured servants. Racialized, chattel slavery did not take hold until after 1640 and was not institutionalized until the 1660s. African slaves were considered property, given only the rights their owners thought prudent, and could only be freed under certain circumstances, including saving their master’s life or a member of the family, informing on other slaves planning an insurrection or escape, or upon the master’s death, but freedom was at the master’s discretion, and it was difficult, especially in the Southern Colonies, for a freed slave to move up the social hierarchy.

Homes & Education

Colonial homes also reflected one’s social status. The earliest houses of Jamestown and Plymouth were wood-framed buildings insulated with wattle and daub (sticks, straw, and mud) with thatch roofs. A wooden frame, often of lashed saplings, would be raised with horizontal sticks tied between the saplings and then vertical sticks woven between these. The spaces between the saplings were then filled with a mixture of mud, straw, and dirt (daub) to form walls and insulate the home.

Most houses were a single room (sometimes with a loft) with a fireplace at one end, dirt floors, and open windows as glass was very expensive. To keep out rain and insects, paper shades or cloth was used and various herbs, such as yarrow, were hung as insect repellent. Adults slept on beds of wood slats and thatch and children on mats on the floor. This style of home continued to be standard for the lower class in rural areas throughout the Colonial Period.

Cities, such as Boston, quickly outlawed the thatched roof to prevent the spread of fire. City homes were wood-frame houses with mortice and tenon beams, wood floors, and often two stories tall with the bedroom on the upper story and the lower for the kitchen, servants, and a front parlor for receiving guests. These often had leaded-glass windows and multiple fireplaces. In time, some of the more expensive were made of stone or kiln-fired-brick.

Plantation houses were often (but not always) mansions with multiple rooms and fireplaces, spacious parlors, and servants’ quarters on the third floor and/or in the basement. They had glass windows, ornamentation, extensive landscaping surrounding them, and would be built of whatever material the owner called for.

Education followed this same model in that the sons of the wealthy were sent to school in England or tutored privately while those of the lower classes were illiterate, taught by their parents, or attended a one-room schoolhouse presided over by a communally funded teacher. The Middle and Southern Colonies had no public schools; only the New England Colonies mandated public education. Parents were expected to contribute whatever they could – whether books, money, desks, or firewood for the school’s central stove – and the teacher was often housed in the parents’ homes on a rotating basis.

Although the New England colonists emphasized the importance of education for all, they still felt that males required more than females as they were expected to go into some sort of business whereas girls were to be married, raise children, and care for the home. Girls were taught the basics of writing and mathematics and, for the upper class, to play a musical instrument, sing, and dance. Boys were taught history, geography, writing, mathematics, and were also instructed in their father’s trade. The Christian religion was standard for any course of education, male or female, but how it was interpreted and taught depended on the colony.

Family, Clothing, Food & Leisure

The family was the fundamental unit of the community, and marriage was encouraged. Most men married in their early to mid-20s while girls could be married as young as 15 years old. Men outnumbered women in the colonies which gave rise to the Jamestown Brides program between 1620-1624, which sent young women from England to Jamestown to be married. The women were assured of a “prosperous match” in that they had their choice between many unmarried men and the prohibitive cost of 150 pounds of tobacco (approximately $5,000.00 in today’s currency) to repay the company sending the women meant only the most affluent male colonists could afford to participate.

Colonial families were usually large and it was not unusual for a woman to give birth to 10-15 children in her lifetime. In rural communities, the children became the labor force and so the more one had, the more profitable one’s farm or business. Extended family members often lived near each other or under one roof and, since women frequently died in childbirth and the widower remarried quickly, there were also stepchildren in the home in addition to aunts, uncles, and grandparents.

All of these hands contributed to the household chores as well as whatever business the head of the household ran. Women and female children wove, sewed, and repaired clothing which could be brightly colored wool or cotton, somber clothes for the sabbath, or animal hide shirts and cloaks. Shoes, especially for men, were often mocassins modeled after those of the Native Americans. Women's clothing was more elaborate than men's and could consist of multiple layers of underwear.

Children were expected to work, not play, and those of most classes were already contributing in some way – even just helping to gather firewood – before five years of age. Still, children did have toys and play games. Girls played with dolls, sometimes made of thatch and discarded cloth, and boys with miniature soldiers, animals, and weapons. Some of the games played were tag, blindman’s bluff, and a ball game known as stoolball (similar to English cricket) while in winter sledding was popular.

Adult males enjoyed games such as bowling, billiards, board games, cards, and hunting for sport. Women participated in 'bees' and 'frolics' both of which were gatherings for some central activity like sewing together a wedding dress or quilt, preserving fruits and vegetables, gardening, or some civic activity like improving a local park. Cooking 'bees' were gatherings of women to prepare a large meal, often in conjunction with a barn-raising by the men of the community.

The colonial diet, especially in New England, was based on corn which could be made into cornbread, corn pudding, corn soup, and muffins. Wild deer, rabbit, squirrel, birds, and other game supplemented one’s diet as well as fresh fruit – apples in the New England and Middle Colonies and peaches in the south. The sweet potato was considered an especially welcome addition to a meal although it was thought to be habit-forming, and anyone who ate sweet potatoes daily was not expected to live past seven years of their first taste. Vegetables, in general, were thought to promote illness unless thoroughly cooked but farmers still planted them, ate them, and showed off the best of their crop at community festivals.

Festivals were occasions for relaxation and celebration and usually took the form of a local county fair. Women competed in contests for best pie or preserves or quilting while men engaged in archery and marksmanship contests, wrestling and boxing matches, and competed for best livestock or largest pumpkin or squash. Children of all ages enjoyed horseback rides at the fair, prizes for climbing a greased pole or catching a pig, hog-calling contests, pie-eating matches, and an abundance of food after a good harvest, which is why most fairs were held in late summer or early fall after the harvest was in.

Crime & Punishment

For those who overindulged at the fair, or anywhere for that matter, and broke with accepted social norms, swift punishment followed and most often took the form of public humiliation. Public drunkenness and breaking the sabbath (working on a Sunday or not attending church), for example, were punished by a certain time in the stocks – wooden braces in the town square which secured one’s hands and neck (and sometimes feet) – during which others might throw rotted fruit and vegetables or small rocks at the person while mocking them.

Forgery, robbery, burglary, adultery, and assault could be punished by public whipping, the stocks, a combination of the two, branding, disfigurement, breaking a hand, arm, leg, jail time, or banishment. Jail time was discouraged because it cost the community money to feed the convict and, while jailed, he or she could not provide for their family.

Rape, murder, and witchcraft were punishable by death, but rape was, unfortunately, difficult to prove, and men – especially upper-class men – usually either paid a small fine or were exonerated. The first recorded execution for murder was that of John Billington (l. c. 1580-1630) of Plymouth Colony, one of the Mayflower passengers, who was hanged. Those convicted of witchcraft were almost always hanged, but the colonists contrived many imaginative and painful methods of death including drowning, burning, and pressing someone to death with weights.

Conclusion

Between c. 1614, when the tobacco crop at Jamestown had become the first successful cash crop of the colonies, through c. 1763, when the English colonists defeated the French in the French and Indian War, a whole new culture developed which was based on the concept of individual effort, strength of character, and adherence to the Christian vision leading to success. The promise of Colonial America was that anyone could become anything they wanted to be if they worked hard enough for it.

Protestant Christianity, which emphasized the importance of hard work in glorifying God, was a motivating and sustaining resource for the colonists from the beginning but took on even more significance in the 1730s during the First Great Awakening when the concept of 'universal godliness' was popularized. Everyone, it was claimed, could be touched by the Holy Spirit, no one was beyond God’s reach, and each individual was precious in the eyes of God. This theological vision set well with the newly formed culture of individualism and, in time, encouraged the radical movement to break away from English rule and form the new nation of the United States of America.