Religion and superstition went hand in hand in Colonial America, and one’s belief in the first confirmed the validity of the second. The colonists' worldview was completely informed by religion and so everything that happened - good or bad - was open to a supernatural interpretation.

The Anglican settlers who established Jamestown Colony of Virginia in 1607 and the Puritans who settled the New England Colonies 1620-1630 were Protestant Christians who believed deeply in God, the reality of the unseen world of angels and devils and understood, based upon their interpretation of the Bible, that everything – large or small – happened for a reason: either God’s will or the devil’s wiles.

Many of the superstitions which developed in Colonial America arrived with the colonists while others were a reaction to the threats and uncertainties of the New World. Although these superstitions are regarded by many in the modern day as irrational, the colonists – for the most part – understood them as conforming naturally to the world as they recognized it.

The Bible made it clear that the devil and his evil spirits were as much a reality as God and his angels and either – or both – could be at work in one’s life at any given time. Superstitions, therefore, developed naturally from religious belief and confirmed the colonists’ worldview (what is known today as confirmation bias) and directed their responses to the events of their lives. As more superstitions were “confirmed” through experience, they became more deeply embedded in the cultural consciousness and periodically found expression through events such as witch trials, banishments, and various persecutions of marginalized segments of the population. Although people in the modern day may find many of the acts of the early colonists incomprehensible, they were a natural development of the superstitions encouraged by the religious beliefs of the time.

Religion in Colonial America

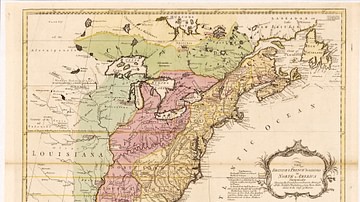

Although it is commonly believed that the English colonies were uniform in religious thought and behavior, this is not so. The colonies of New England were established by separatists (Plymouth Colony) and Puritans (Massachusetts Bay) but over half of the passengers on the Mayflower, which brought the separatists to Plymouth, were Anglicans who worshipped differently, observed Christmas (unlike the separatists and Puritans), and rejected the separatists’ strict moral and behavioral code.

Dissension among the Puritans of Massachusetts Bay Colony was apparent as early as 1633 when Roger Williams (l. 1603-1683) was exiled for contradicting the Puritan magistrates of Boston. He would then establish Providence Colony (modern-day Providence, Rhode Island), which advocated a much more liberal theology, and the colonies of Connecticut and New Hampshire followed this same model as they were also developed by exiles from Massachusetts Bay.

The New England Colonies each insisted their interpretation of Christianity was correct and others were wrong and the same was true all the way down the eastern seaboard. The Quakers who established Pennsylvania were religiously tolerant, welcoming people of all faiths, but still believed their understanding of the Bible was the only right one.

In Virginia, the Anglican Church was thought to be the true church, rejecting not only Catholicism but any other Protestant sect, while Maryland was founded as a haven for Catholics who claimed their church as the original founded by Saint Peter through the authorization of Jesus Christ himself. Religious conflict in Maryland eventually resulted in Catholic persecution and the deportation of Jesuit priests. North and South Carolina followed the Virginian model but, as with all the colonies, not every citizen accepted the view that the 'official' church ordained by God was the Anglican Church and there were invariably conflicts just as there were in the more tolerant and diverse colonies of New York and New Jersey.

All of the colonies could agree on one basic truth of their faith, however, and that was that God was a reality and was ultimately in control of their lives. They could struggle against God’s will, even defy it, but God had the last word. Satan and his demons could try as hard as they liked to disrupt God’s plan but, in the end, according to the assurances of the biblical Book of Revelation, God’s will would prevail.

Omens & Luck

It was not always easy to see God’s hand in daily events, however, especially when these were disappointing or tragic. The death of a young child or a woman in childbirth would be attributed to God’s will but why he should have wanted to take those lives was difficult to understand. Reasons given might range from one’s sins, the community’s sins, diabolic influences, or simply the mysteries of the divine which were beyond human understanding.

Even if one lived the purest of lives as best as one could, one would still experience misfortune, and there seemed little anyone could do about that but accept it. One could catch a glimpse of God’s plan, however, by recognizing omens and acting accordingly. If one avoided crossing the path of a black cat, for example, one was thought to have prevented some minor or major tragedy in the same way throwing spilled salt over one’s shoulder or taking special care on Friday the 13th would.

One especially popular belief in signs and omens was expressed through the practice of moon watching (also known as moon farming) whereby people understood when to plant and harvest crops or engage – or not – in any other activity by observing the phases of the moon. Scholar David Freeman Hawke comments:

A sampling of the lore handed down through the [seventeenth] century reveals that pole beans should be planted when the horns of the moon are up, to encourage them to climb; but a farmer must not roof a building then, for the shingles will warp upward. He should plant root crops during the “dark of the moon” but not pick apples, which will rot regardless how they are stored…No one in the seventeenth century questioned the validity of moon farming, and faith in it persisted far into the future. (159-160)

One could take one’s chances, of course, and plant crops or roof buildings whenever one liked, but it was understood that God had provided the phases of the moon for the benefit of his people and one would do well to recognize and take full advantage of that.

The concept of luck was somewhat trickier to define because if luck were understood as chance then it should not exist in a world governed by an all-knowing and all-powerful God. Everything that happened, happened according to God’s will and so where was there room for chance in this? It came to be understood that God had a hand in luck as well as anything else in that he had provided people with the stars and planets, as well as many other common earthly signs, to direct the course of peoples’ lives. Omens were clearly provided by God to help people make wise choices, it was thought, and if one failed to recognize them that was the individual’s, not God’s, fault.

Paying attention to signs and omens even extended to leisure activities. The gentlemen of Virginia, for example, paid special attention to planetary movements and astrology in gauging their chances of success in gambling. This gave rise to the concept of the stars being aligned in one’s favor. If one paid attention to God’s signs, one could walk away from the gaming table a richer man at the end of an evening, and if not, one would suffer loss after loss. It was not luck that dealt a winning or losing hand at cards, it was God. As more and more people provided anecdotal evidence of the truth of various superstitions – such as "beginner’s luck" – more came to find evidence of that truth in their own lives.

Superstitions in Colonial America

These superstitions, like those of any culture, encouraged communal values but they also expressed the community’s guilt and fears. Belief in the so-called "Indian Curse" can be understood as expressing unaddressed guilt over the colonists’ mistreatment of the natives and unconscious recognition of deserved punishment, while the superstition regarding bad luck following the purchase of a horse with white feathering over all four hooves may have originated in an inability to tell at a glance if the horse was healthy. Since horses were expensive, and few colonists had disposable income, paying attention to a sign such as not being able to see the state of a horse’s hooves was considered vital in making a sound purchase. The horse’s feathering, therefore, was interpreted as a sign to purchase or not purchase the animal.

Believing that everything happened according to God’s will, the colonists found reasons for events even when there was no clear connection between the effect and the cause. An example of this is the belief that if a woman allowed a fire to go out while preparing a meal, her husband would become lazy (or if the meal were being prepared by an unmarried woman, then one’s future husband would be lazy). Conversely, if a young, unmarried, woman was skilled at building and maintaining the hearth fire, she would find a good husband. Superstitions like this one encouraged women to become skilled in making and keeping a fire going on the hearth which was important in a time when, lacking matches, starting a fire could be difficult and keeping it going was important both for heating, making meals, and preparing herbal remedies.

Events which seemed unexplainable to the colonists, such as a fire going out or starting for no reason, found an answer in the supernatural world as depicted in biblical narratives (an angel put the fire out to prevent it from catching the house on fire or a devil started the fire in the haybarn), and once the supernatural was accepted as reality, any seemingly inexplicable event could be ascribed to it. If a piece of wood fell out of the fire onto the hearth once and then a guest knocked at the door, that might just be coincidence, but if it happened more than once – and to more than one person – that was a sure sign of supernatural energies at work and gave birth to the superstition that if a log fell from the fire onto the hearth, it signaled the arrival of a visitor. The number 3 became especially significant in cases such as this, and if an event happened in more or less the same way three times, especially close together in time, it was recognized as a supernatural pattern of significance and led to the belief in bad luck coming in threes.

Many of the superstitions of the colonists of lower North America arrived with them – such as the belief in black cats bringing bad luck, Friday the 13th as particularly inauspicious, a groom not seeing the bride on the wedding day, the dangers of a broken mirror – but others were encouraged by the so-called New World they encountered. The deeply held belief in the "Indian Curse", for example, developed wholly in Colonial America and, most likely, as a subconscious response to guilt over colonists’ treatment of the natives.

Responses to Native American Conflicts

One of the best-known "Indian Curses" is the curse of the Saco River in modern-day Maine. According to one version of the legend, a native chief named Squandro lost his infant son (and in some versions also his wife) when three drunk English sailors threw the child into the river to see how well he could swim. The child drowned (and, in some versions, his mother drowned trying to save him), and the chief leveled a curse that three white people would drown every year in the river to atone for his loss. Although this legend does not appear in written form until the late 19th century, it is thought to have originated in the Colonial Period. Many people in present-day Maine still believe in the curse of the Saco River and the legend serves the same purpose now as it did in the past: to explain an otherwise inexplicable, or unbearably tragic, event.

According to some oral traditions, Squandro was a powerful sachem (chief) of the Sokokis tribe which was allied with the Wampanoag Confederacy under the leadership of Metacom (also known as King Philip, l. 1638-1676) and the deaths of Squandro’s son and wife contributed to the outbreak of King Philip's War (1675-1678). This conflict devastated the New England colonies as well as the Native American tribes of the region. The story of the death of Squandro’s family and his curse may have developed as a way to relieve colonial guilt over the atrocities perpetrated on Native Americans during and after the war when many were sold into slavery, killed indiscriminately, or relocated to reservations, even those tribes which had no part in the conflict. One could find meaning in the drowning death of a loved one by attributing it to the curse.

Witchcraft & Dark Magic

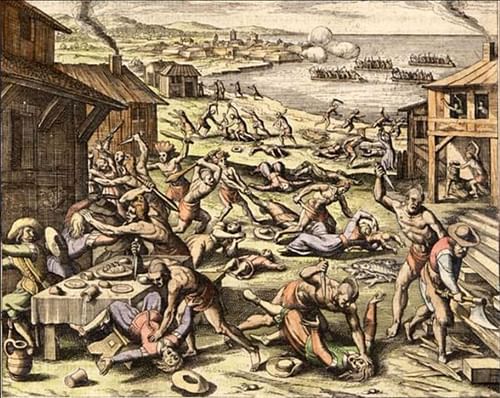

The power of the "Indian Curse" – whether in New England or in Virginia, as in the case of the equally famous Curse of Chief Cornstalk – was considered an irrefutable truth by the colonists because of their belief in the Native Americans as diabolical servants of Satan. This belief was strengthened early on by the Indian Massacre of 1622 in Virginia when, on the morning of 22 March 1622, the chief of the Powhatan Confederacy, Opchanacanough (l. 1554-1646) launched a surprise attack on the settlements, killing 347 people. Prior to the attack, the natives had appeared friendly (purposefully so, on Opchanacanough’s orders, to lower the colonists’ defenses), and this, to the colonists, was proof that no native could be trusted and all posed a potential threat.

The belief in natives wielding supernatural powers continued, however, as they became more marginalized, and it was understood that they had grounds for holding a grudge. Other minorities were equally apt to be suspect though, whether African slaves – who were thought to be able to cast spells through their own associations with Satan – or Catholics whose religious beliefs were considered diabolic by the majority of Protestants.

Witchcraft, thought to be practiced by all three of these groups, was understood as an intimate relationship between a person or people with Satan himself, God’s adversary, who continually plotted against those whom the Bible claimed God had made in his own image. Although the Salem Witch Trials are easily the most famous expression of the fear and hysteria generated by a belief in witchcraft, marginalized people – most often women – were charged, convicted, and hanged or otherwise dispatched in colonies from Massachusetts down to Florida.

Conclusion

Superstitions were embraced further during the 1730s and 1740s through the religious revival known as the Great Awakening when Protestant ministers held large open-air services to awaken the Holy Spirit in the people. Thousands attended these gatherings at which they were "born again" and went home full of the conviction that their lives were to be lived as soldiers in God’s army against the legions of darkness. Every demographic in the colonies was caught up in the Great Awakening – colonists, natives, and slaves – and the majority of these were the poor and uneducated, those who had been marginalized by the upper classes.

Intensely emotional and personal in nature, the born-again experience needed no outside corroboration – the believer experienced the power of the Holy Spirit immediately and dramatically – and there was no need to argue rationally for the truth of the experience when its results were so apparent in one’s life. The Great Awakening encouraged people to "fight the good fight" for God whether by becoming more involved in politics or rooting out witches and other evildoers in their local community. In time, however, this religious emotionalism – which encouraged superstitious belief on a deeper level than before – was met by a backlash of rationalism and restraint.

By the 1750s, the example of upper-class gentlemen, who espoused deism – the belief in a god but not a specific god – encouraged those of the lower classes to follow suit. This is not to say that evangelical, born-again Christianity was suddenly abandoned – it most certainly was not – but the upper-class encouraged a more restrained response to the Christian vision. Unitarianism – which held that all beliefs were equally valid – developed in the colonies around 1774, and the Founding Fathers – almost all deists – based their understanding of government on rational, not supernatural, concepts.

Even so, superstition had become rooted in Colonial American culture and persists even in the present day. People across the United States scoff at the beliefs of the colonists while simultaneously taking special precautions when the 13th of the month falls on a Friday, avoiding black cats, and in many other ways reacting to the unseen world just as the early colonists did.