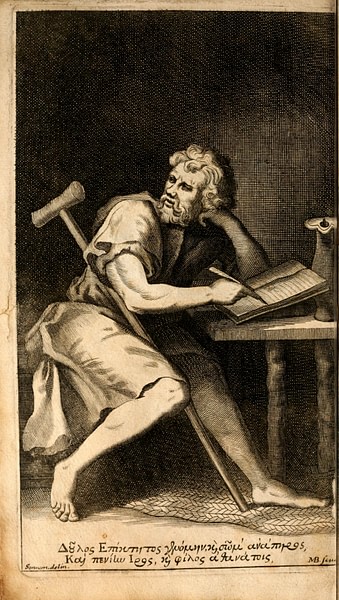

The Stoic philosopher Epictetus (l.c. 50- 130 CE) following the example of Socrates, wrote none of his teachings down, preferring to impart his wisdom to his students through class discussions. His student Arrian collected and edited the lectures and discussions he attended in eight books, of which four remain extant, and distilled his master's thoughts in the Enchiridion (`Handbook'). That philosophy was a way of living, not merely an academic discipline, is apparent throughout the Enchiridion and is expanded upon in his other work, the Discourses. Though born a slave, Epictetus gained his freedom and taught both in Rome and Greece. He learned Stoic philosophy first from his master and developed the fundamental ideas into a philosophy which he felt could liberate one from the slavery of circumstance.

Epictetus' focus was on the responsibility of the individual to live the best life possible through self-control and a recognition of a force in the universe he called the logos. He insisted that human beings do have freedom of choice in all matters even though that choice may be limited by the natural operation of this logos. The logos (Greek for `word' but also with a wider meaning of `to convey thought') was an eternal force which moved through all things and all people, which created and guided the operation of the universe and which had always existed.

In many English translations of Epictetus' works logos is often given as God. Scholar Gregory Hays notes:

Logos operates both in individuals and in the universe as a whole. In individuals it is the faculty of reason. On a cosmic level it is the rational principle that governs the organization of the universe. In this sense it is synonymous with “nature”, “Providence” or “God”(when the author of John's Gospel tells us that `the Word' – logos –was with God and is to be identified with God, he is borrowing Stoic terminology. (xix)

This logos, then, came to be synonymous with the monotheistic Judeo-Christian understanding of God but the seemingly `mysterious' workings of the Universal Mind were not considered by Epictetus to be mysterious at all. The logos was the natural, ever-present, force of life which could be apprehended and understood through reason, not through faith in underlying and unseen good intentions of a benevolent deity.

Because of the natural operation of this logos the individual was limited in choice (one could not `choose' to defy the immutable laws of existence) but still had the power over how to interpret external circumstance and how to respond to it. As the Enchiridion puts it:

Men are disturbed not by the things which happen, but by the opinions about the things: for example, death is nothing terrible, for if it were it would have seemed so to Socrates; for the opinion about death, that it is terrible, is the terrible thing. (V)

How one chooses to interpret external circumstances, not the circumstances themselves, leads one to enjoy a good life or suffer from a bad one. The immense power, and responsibility, of personal choice and freewill was at the heart of the Stoicism of Epictetus while he simultaneously acknowledged that there was much in life which was simply beyond one's control. Hays notes:

The Stoics [defined] free will as a voluntary accomodation to what is in any case inevitable. According to this theory, man is like a dog tied to a moving wagon. If the dog refuses to run along with the wagon he will be dragged by it, yet the choice remains his: to run or be dragged. In the same way, humans are responsible for their choices and actions, even though these have been anticipated by the logos and form part of its plan. (xix-xx)

While it may be tempting for a modern reader to interpret this `plan' as synonymous with a present day religious understanding of `God's Plan' which must be accepted on faith (not necessarily understood) that was not Epictetus' meaning.

The `plan' of the logos was the rational, natural, maintenance of the world which includes, for human beings, aging, sickness, disappointment, and death. These things, which humans define as `bad' or `tragic', are, to the logos, simply a part of the human experience. The logos is not sending `trials' or `tests' to people nor, according to Epictetus, are any of the aspects of human life which are regarded as negative anything other than natural and normal.

Because of the biological make up of a human being, that organism will be subject to age, sickness and death and, because of the psychological make up, a human will experience disappointment when expectations are not met. An important aspect of the foundation of Stoicism is Heraclitus' claim that "Life is Flux", everything is always changing, and so the disappointment one experiences today cannot last into tomorrow unless the person who has been disappointed chooses to make that so. Human beings create their own realities when they lose sight of the rational workings of the logos.

Epictetus claims that the path to freedom from suffering is by accepting the natural order of life and recognizing that, things being as they are, humans will often experience circumstances they will find unpleasant. Acceptance of the human condition, then, is the first step toward liberating oneself from the expectation that life should be any different than what it must, of necessity, be according to the operation of the logos. The second step in liberation is self-control regarding impressions and interpretations we make on a daily basis.

Our lives may be subject to constant change but we are ultimately responsible for how we interpret and respond to those changes. By accepting responsibility for the way we view the world, and how that view affects our behavior in the world, we free ourselves from external circumstances to become our own masters and no longer slaves to time and chance.