In medieval and Renaissance Europe, dogs were considered little more than 'machines' which performed certain tasks, such as guarding a home or tracking game, but this view changed significantly during the Age of Enlightenment (also known as the Age of Reason) of the 17th and 18th centuries.

The Age of Enlightenment was an intellectual movement among the upper-class intelligentsia, which encouraged a re-evaluation and reinterpretation of widely held beliefs concerning the human condition. Prior to the Protestant Reformation (1517-1648), the Catholic Church had shaped European interpretation of life and one’s place in the universe, but afterwards, individuals were encouraged to seek a personal relationship with God based on their own understanding of scripture and this led to greater freedom of spiritual and intellectual pursuits which eventually found expression during the Age of Enlightenment.

Among the many advances this period produced was a re-evaluation of the dog. The Church had declared that dogs were soulless beings and should not be treated with the same regard as humans who had been endowed with an immortal soul. One of the most significant thinkers of the Enlightenment, René Descartes (l. 1596-1650), the philosopher some cite as the "Father of the Enlightenment", decided to prove the Church’s claim true or false by dissecting dogs while they were still alive, even his wife’s pet dog and, finding no evidence of a soul, concluded the Church was correct.

Later thinkers, artists, and poets disagreed with Descartes, however, and featured the animals in their works, often excluding human subjects. Dog collars, which were previously utilitarian devices for controlling the animals, became ornate works of art. Collars were so valuable, in fact, that laws were enacted punishing people for the theft of a collar more severely than if they had stolen the dog itself. The Age of Enlightenment dramatically changed the way people viewed and treated dogs and eventually encouraged the development of societies dedicated to their safety, comfort, and well-being.

Dogs in Art

In 1434, the Flemish artist Jan van Eyck (l. c. 1390-1441) painted what is arguably his masterpiece, the Arnolfini Portrait, of a man and woman in a room with a dog. The two people, presumably a husband and his pregnant wife, seem to be in the midst of a serious discussion, but the small dog at their feet looks attentively out toward the viewer. The painting has long been praised for its intimacy and realism, and this dog is an important aspect of that. This dog has no concern at all for whatever drama may or may not be unfolding between the two humans; its attention is on the stranger - the person now viewing the painting - who has just walked in on this scene.

Impressive as the work is, no other artists chose to represent dogs in such an intimate and realistic manner again until the 18th century when paintings begin to regularly feature the upper class in the company of a favorite dog. The painting Miss Mary Edwards (1742) by the English artist William Hogarth (l. 1697-1764) shows the woman at her writing table stroking the head of her spaniel and A Woman with a Dog (1769) by French painter Jean Honore Fragonard (l. 1732-1806) catches a woman holding up her small white lapdog, wearing a blue-ribbon collar and leash, as though the viewer has just opened the door and surprised her. The dog in this painting, unlike in van Eyck's, takes no notice of the intruder and only has eyes for its mistress.

Dog collars in these paintings and many others, when they are shown, are often bands of gold or silver or, as in the case of Fragonard's piece, ribbon. In many of the Enlightenment paintings which feature dogs, the focus is clearly on the human subject with the dog playing a secondary role in the composition until one artist decided to elevate the dog in art and, in doing so, changed the way people saw dogs in their daily lives.

Stubbs & the Dog

George Stubbs (l. 1724-1806) was an English painter who is probably best known for his depictions of horses. His work with dogs, however, was revolutionary because the dog became the essence of the painting and this suggested that dogs were worthy of that kind of attention and consideration. A fascinating aspect of Stubbs' work is that his dogs have no collars; they are presented as subjects worthy of consideration without reference to a human owner and, in many, with no human presence suggested.

Even in compositions like Huntsman with a Grey Hunter and Two Foxhounds (1760-1761) which includes a human subject and a horse along with two dogs, the dogs are not collared, and they look at each other as though in conversation with little regard for the man and his horse. In A Repose After Shooting (1770) one hunter rests beneath a tree with two dogs as a second steps toward him holding some game. The dogs, neither of which wear collars, look up toward the second man in the same way as the reclining hunter suggesting a complete equality between all three.

All of Stubbs' dogs are depicted as individual, sentient, beings who are just as worthy of respect and care as any human being and are carefully represented as individuals with a specific character. Stubbs was already famous for his realistic and striking horses by his mid-thirties and, though he continued to accept commissions for human portraits, devoted a significant amount of time to painting dogs and, in doing so, elevated their status more than any other painter of his time. If such a famous and talented artist thought the dog worthy of such effort, it was reasoned, others should reconsider how they viewed the animals.

Reinagle’s Musical Dog

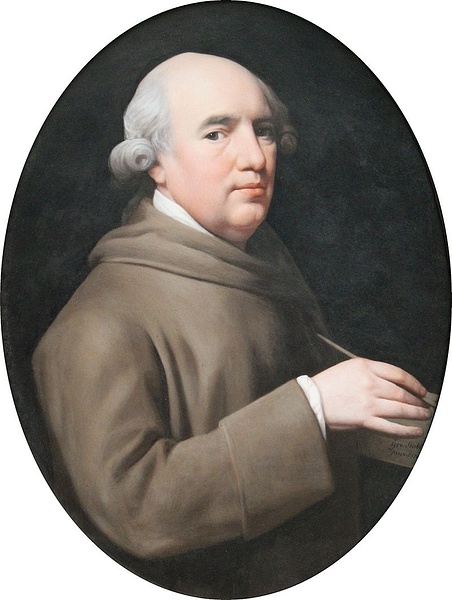

Stubbs’ work with dogs inspired other artists to do the same, and among them was the English painter Philip Reinagle (l. 1749-1833). Reinagle was the student of the famous portrait painter Allan Ramsay (l. 1713-1784), who held the court position of Principal Painter in Ordinary under King George III of England (r. 1760-1820). Reinagle completed many of Ramsay's portraits as well as his own commissions until he became tired of painting people and turned his attention to dogs. It may be significant that Reinagle does not change his subject matter until after his master's death in 1784, but from 1785 onwards, he popularized the dog in portraiture throughout Europe. Reinagle was especially known for his paintings of spaniels, a very popular dog of the day, and the subject of one of his best-known works.

Reinagle's Portrait of an Extraordinary Musical Dog (1805) depicts a brown spaniel with a red collar sitting at a piano with an open score before him. An open window, in the background, shows a pastoral landscape. The dog, paws on the keys and head turned from the window, looks toward the viewer as though one has just interrupted him at playing. The composition carefully mirrors a popular pose of the day in which a young woman would sit at a piano (open window of landscape behind or, perhaps, shelves of books), gazing toward the viewer.

Scholar Lawrence Libin of the Metropolitan Museum of Art observes that the musical score open on the piano is God Save the King and that Reinagle, well versed in music and notation, purposefully crafted a satire of the popular portraiture of the day right down to the music the dog is seen playing from (Libin, 97). The focus of the composition is the dog who looks toward the viewer with a surprised expression as though having just been interrupted at practice. The dog's red collar matches the piano stool, and both reflect the reddish-brown of the piano and the dog's coat to keep a viewer's eye closely concentrated on the painter's vision: a dog playing a popular, and political, tune on the piano.

Dog Collars of the Talented & Famous

This new appreciation for the dog continued throughout the 18th century. Dog collars of the time are often incredibly ornate as seen in two of the pieces from the Leeds Castle Collection in Kent, England, items H31 and H32 (Leeds Castle, 14 & 15). H31 is a hinged English brass collar decorated with scallop-shell and rosette escutcheons and engraved with the owner's initials, while H32 is a hinged iron and brass collar from Germany elaborately decorated with baroque scrollwork. Collars were also sometimes inscribed with pithy sayings related to the dog's character or the owner and easily the most famous of these is by the great English poet Alexander Pope (l. 1688-1744) best known for works such as The Rape of the Lock, his epigrams, and his other satirical verses.

Pope's constant companion was a Great Dane named Bounce who, by all accounts, was very well behaved and a model dog. Bounce is said to have once saved Pope's life from a newly hired valet who sought to kill and rob the poet in his sleep. Bounce had seemed instantly suspicious of the man and left his usual spot at bedtime to hide under Pope's bed and keep watch. When the man entered the room stealthily, Bounce alerted the house, and the would-be assailant was arrested.

Bounce was greatly admired by Frederick, Prince of Wales (l. 1707-1751) who was a friend of Pope's and would often visit the poet at his estate at Twickenham. One day, when the prince arrived, he was given one of Bounce's puppies, which he took back to the royal kennels at Kew Gardens. Shortly after this, a collar arrived for the dog with the inscription: I am his Highness' dog at Kew - Pray tell me, sir, whose dog are you? News of this couplet traveled far, and it seems to have become quite popular. The ornate brass collar from the Leeds collection, number H39 (Leeds Castle, 22) is dated from the late 18th century and has a variation of Pope's couplet inscribed on it: I am Mr. Pratt's Dog, King St. Nr. Wokingham, Berks. Whose dog are you? This latter work obviously lacks the finesse and charm of Pope's work, but this is why Pope is considered a great poet and Mr. Pratt is not. The Pratt collar is not the only one to borrow from Pope's couplet which continued to be popular with dog owners a century later. Another collar, made of brass and dated to the mid-1800s, is engraved: I'm Thos. Thompson's Dog. Whose Dog are You?

The ornate dog collar of leather with an engraved plate attached became so popular it even migrated to the English colonies of North America where dog ownership established one’s social status and such collars enhanced it. The padlock collar, a hinged metal ring attached around the dog’s neck and held by clasps fastened by a padlock, became especially popular in the colonies. The owner held the only key to the lock and so, if the dog were stolen, one could establish ownership by producing the key and unlocking the collar. These collars did not need the engraved plate to establish ownership but that does not mean that they did not have them as a status symbol.

Evidence of the increasing personal interest in the dog as a pet and companion is seen throughout the rest of the 18th century in the colonies and in continental Europe. A famous European example is the dog of the French polymath Pierre Beaumarchais (l. 1732-1799) or, actually, that dog's collar. Beaumarchais had his dog Floretta's collar engraved with "Je m'appelle Floretta. Beaumarchais m'appartient!" (My name is Floretta. Beaumarchais belongs to me!). Beaumarchais was famous in his own time for his writings, music, and revolutionary fervor, and the wit of his dog's collar was seen as a reflection of his intellectual gifts.

As with Pope's epigram in England, Beaumarchais's became a popular sentiment among dog lovers on the Continent. One still sees this very same concept expressed today in bumper stickers and amusing signs claiming that one is owned or has been well trained by one's dog.

Dog Collars & Elevated Status

It would seem there is some truth to this claim as dogs increasingly came to be regarded as esteemed family members, often receiving better treatment than humans of the home. Dogs of the upper-class often had their own pillows and groomers, and even working-class dogs were treated better than they had been previously. The draft dog pulled carts of varying kinds through the streets of London as they were cheaper to keep and feed than a horse or mule. Draft dogs came to be regarded as members of the family and business just as other dogs did in the upper-class homes. The large Greater Swiss Mountain breed was a favorite for pulling large carts and smaller breeds for littler ones.

Each dog had a collar identifying it and the owner even if it worked in a harness all day.

The dog collar identified the dog in the same way a human's personal documents verified their identity. Dogs were legally considered private property and a collar was the physical evidence that a dog belonged to a specific individual. In 1845, the Dog-Stealing Bill was passed into law which made it a criminal offense to take another person's dog. Prior to this bill, the punishment for taking a dog's collar - but not the dog - was seven years in prison. A collar, often ornate and expensive among the upper class, was obviously the property of the person whose name was engraved on it. It was only after the Dog-Stealing Bill was passed that the dog who wore the collar was equally valued under the law.

Conclusion

Although the law was slow in recognizing the value of the dog, increased public awareness of, and affection for, dogs as pets had been growing since the early years of the Age of Enlightenment which would continue to build momentum throughout the 19th century. Although the dog was more highly regarded than it had been, generally speaking, during the Middle Ages and early Renaissance, it was still subject to poor treatment through events such as public dog fights, bear baiting (in which a dog would fight a chained bear), as well as indiscriminate acts of cruelty by people who, for some reason, thought they were better than dogs.

The RSPCA (Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals) was founded in 1824 as the first organization to promote the welfare of animals in the world. Although the Massachusetts Bay Colony of North America had passed the first law relating to the mistreatment of animals, the Regulation against Tyranny or Cruelty, in 1641, that law did not establish an organization, nor had it any reach beyond that colony. The aim of the RSPCA was not only to protect animals from harm but bring those who purposefully injured them to justice. In its first year, it was able to effect the arrests of 63 people charged with cruelty to animals and became even more effective after it was patronized by then-princess and later Queen Victoria (r. 1837-1901) whose favorite pet was her dog Dash long before she became an admirer of cats.

Although the RSPCA made a number of serious mistakes early on which wound up harming more animals than intended (such as the London Police Act of 1839 which inadvertently caused the deaths of thousands of dogs), it still did more good than harm and continued to call attention to animal rights and the basic dignity and respect due to all living creatures. Similar organizations were eventually established in other countries which further elevated the dog’s status as the ubiquitous best friend of humanity, and in the modern day, dogs are among the most popular and pampered pets in the world, rivaled only by cats, late-comers to widespread popularity who benefited significantly from the attention paid earlier to the dog in the Age of Enlightenment.