Constantine I (Flavius Valerius Constantinus) was Roman emperor from 306-337 CE and is known to history as Constantine the Great for his conversion to Christianity in 312 CE and his subsequent Christianization of the Roman Empire. His conversion was motivated in part by a vision he experienced at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in Rome in 312 CE.

Constantine’s Rise to Power

During the Crisis of the Third Century, the Roman Empire had suffered multiple difficulties: drought, famine, plagues, inflation, invading barbarians. Numerous Roman generals had fought over the rule of the empire, resulting in civil wars and the rule of the so-called barracks emperors who were chosen and often quickly replaced by the Roman army. When the dust cleared, Emperor Diocletian (r. 284-305) divided the empire into East and West and appointed co-emperors. Beneath the co-emperors, he appointed Caesars and Augusti to delegate Roman rule. Constantine’s father, Flavius Constantius, was one of the Caesars of the Western Roman Empire and was later elevated to Augustus. Diocletian then took the unprecedented step of retiring to his villa at Split (modern-day Croatia) in 306 CE.

When Constantius and his son battled the Picts in England, Constantius was killed near York in 306 CE, and the legions proclaimed Constantine Augustus on the field. With the retirement of Diocletian, the next several years saw civil wars in both the East and the West over who would become the sole ruler of the empire. Constantine’s opposition in the West was Maxentius and their armies met near the Milvian Bridge in Rome, a bridge across the northern outskirts on the Via Flaminia. Maxentius fell into the river (with his armor) and drowned. Constantine became the sole ruler in the West.

The night before meeting at the Milvian Bridge, Constantine prayed for success in the coming battle. Either in a vision or a dream, he saw an image with the script "In Hoc Signo Vinces" ("In this sign, conquer"). Controversy still swirls around both the event and the image that he saw.

We have two sources for the story: Eusebius (260-340 CE), Constantine’s court bishop, and Lactantius (Lucius Caecilius Caecilius Firmianus 250-325 CE), a court adviser and tutor to his sons. Both these men related the story, but only years after the event. Eusebius reported that Constantine saw the sign of the cross, while Lactantius said it was the superimposed letters chi and rho (the first two letters of 'Christ' in Greek). Whatever Constantine saw or experienced, he credited his victory to the Christian God.

The Edict of Milan

Although Constantine is acclaimed as the first emperor to embrace Christianity, he was not technically the first to legalize it. In the 3rd century CE, various generals issued local edicts of toleration in an effort to recruit Christians into the legions. These edicts then fell by the wayside when the contender was killed in battle.

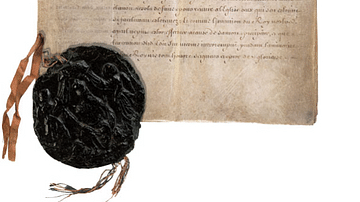

In the Eastern Empire, Galerius (r. 305-311 CE) initially had persecuted Christians but reversed it through the Edict of Toleration in Serdica in 311 CE. Licinius (r. 308-324 CE) had also persecuted Christians sporadically but took the edict of Galerius as a model and met with Constantine in Milan to unify positions. The Edict of Milan was issued in 313 CE, with the added stipulation that Christian property that had been confiscated or destroyed would be returned or compensated with funds.

The word 'toleration' (Latin: tolerantia ("endurance") is often used to describe Rome’s position vis-à-vis the numerous native cults. However, there was no official policy, and what was tolerated was the religious pluralism; everyone respected the gods of others. Rome had a system of collegia, specialized tradesmen and businessmen, who met for shared meals under the auspices of a god or goddess. To meet, the group had to have permission, a sort of license, from the Roman Senate. The term religio licta ("legal religion") is often used, but it was actually coined by Bishop Tertullian (2nd century CE) in his petition for such a license for Christian meetings. His petition was denied at the time.

The Edict of Milan now granted Christians throughout the Empire toleration and permission to meet in their assemblies and so legalized the movement. Christianity was now just one more of the thousands of native cults throughout the Empire.

The Religious Background of Constantine

Scholars continue to debate and examine the rationale for Constantine’s conversion to Christianity. One element involves attempts to determine the demographics of the Roman Empire c. 300 CE. Christianity had grown steadily since the 1st century CE, and by 300 CE, there are estimates that out of a total population of 60 million, 3 million were Christians. (Jews still numbered 11 million). Some contend that Constantine was smart enough to foresee the winds of change. However, Constantine may have perhaps been pre-programmed for some of his beliefs.

During the reign of Emperor Aurelian (r. 270-275 CE) the cult of Sol Invictus ("the invincible, unconquered sun") was promoted as his family cult. This cult also embodied concepts of Jupiter, Apollo, and Helios. Sol Invictus merged with another popular military cult, that of Mithras. At the same time, Aurelian also reorganized imperial finances and regulated imports and the price of food throughout the provinces. His ideals may be summarized as "one god, one empire". Constantius and his son Constantine were both members of the cult of Sol Invictus.

Constantine was most likely exposed to Christian teachings in his travels with his father. It was reported that he helped some Christians receive compensation for damaged property near Trier, before his conversion. He also spent time and received his education in various imperial courts (particularly under Diocletian). We cannot confirm if his mother, Helena, was a Christian before her son’s conversion; such details are only found in later, legendary stories of her.

A Committed Christian?

Many books on Constantine continue to debate Constantine’s commitment as a Christian. Criticism of Constantine's conversion involves the following elements:

- The Edict of Milan legalized Christians but left all the native cults in place.

- The Arch of Constantine (erected in 315 CE near the Colosseum) lacks Christian symbols and contains sculptures of offerings to Apollo, Diana, and Hercules.

- Constantine issued coins with himself in the figure of Sol Invictus and Helios.

- Constantine was not baptized as a Christian until he was on his deathbed.

Whether any of the above points can be interpreted as a lack of commitment is debated. Constantine inherited a vast empire, where he expected loyalty from all citizens. He could not abruptly eliminate the old Roman religion, the traditions of the ancestors which were incorporated into daily life. The native cults would not be outlawed until the edict of Theodosius I in 381 CE.

The triumphal Arch of Constantine was commissioned by the Roman Senate in 315 CE to celebrate his victory over Maxentius. Scholars debate if the arch was built utilizing older arches to Trajan, Hadrian, and Marcus Aurelius to explain the incorporation of these symbols. We do not know how many Christians were in the Senate at that time, but the Senate was always a conservative body.

All emperors promoted their family cults on their coins. However, we cease to find such coins after 319 CE, for unknown reasons. In 321 CE, Constantine forbade Christians to make offerings at native temples. In reorganizing fiscal policy, he had many of the native statues melted down to mint new coins.

The most debated topic of Constantine’s conversion is his baptism. Given the civil wars that were rampant in this period, the best explanation is that Constantine knew that as emperor, he was going to have blood on his hands. In this sense, he was quite typical. He executed one of his wives and their son (possibly because of rumors of sexual immorality). Waiting to the very end to have your sins forgiven made perfect sense in his world. Despite the delay of baptism, throughout his reign Constantine was quite open about his Christian convictions in his letters and speeches:

This God I invoke with bended knees, and recoil with horror from the blood of sacrifices, from their foul and detestable odors, and from every earth-born magic fire: for the profane and impious superstitions which are defiled by these rites have cast down and consigned to perdition many, nay, whole nations of the Gentile world. (Eusebius, Life of Constantine, IV, chapter X, quoted in Schaff)

While native cults and traditions remained, Constantine favored Christians both financially and theologically. As their supreme patron, Constantine endowed Christians with funds to build their basilicas and to acquire property, returned confiscated property, named Christians to high-ranking offices, and exempted Christian clergy from taxes. In theological support, his position as head of the Church as well as the empire contributed to imperial dictates that promoted Christian unity of belief.

The Donatist Schism

During the persecution against Christians under Diocletian (302-306 CE), in addition to arrests, the emperor had ordered Christian clergy to hand over their sacred texts. To avoid imprisonment and the arenas, some, including bishops, had done so. Divisions had grown among the Christian communities, and one group, led by Bishop Donatus, was adamant that these bishops were now defiled. The bishops petitioned Constantine to act as a mediator in this problem. After so many civil wars, Constantine was determined to instill unity throughout the Roman Empire and ordered a policy of "forgive and forget."

Bishop Donatus refused and his followers settled in North Africa where they clashed with Augustine of Hippo a hundred years later. By issuing the order, Constantine effectively became the official head of the Church. This mirrored Augustus (r. 27 BCE - 14 CE) when he combined the position of pontifex maximus, the head of Roman religion, with his role as first citizen. In 324 CE, Constantine defeated Licinius and became the sole emperor. In that position, he essentially expanded the ideas of Aurelian, in that he could now enforce "One God, One Emperor, One Church".

The First Council of Nicaea

After mediating the Donatist Schism, his next major challenge came in 325 CE. A presbyter in Alexandria, Arius, had been teaching that at some point, God had created Christ. Riots had broken out in several cities, and Constantine brought the bishops together at the city of Nicaea to resolve the issue. The Council of Nicaea resulted in the Christian doctrine known as the Trinity, which articulated the relationship between God and Christ. The Council voted to claim that Christ was of the identical essence of God, present at creation, and manifest (incarnated) on earth in Jesus of Nazareth. Until Christ returned, the now Christian emperor stands in for Christ, and so carries the identical power of God on earth as he rules. It was after this council that Christian emperors began to be portrayed with halos over their heads, and the trappings of divine worship.

The concept of a creed (from the Latin credo, "I believe") was a Christian innovation. With multiple native cults, there was no central authority that dictated what all should believe. The Nicene Creed formalized one system of belief that was promoted through the power of the emperor. As such, any dissent was not only heresy but also treason.

The Council of Nicaea also set the date for the empire-wide celebration of Easter. Some communities had insisted on following the gospel tradition of observance during the Jewish Passover. Constantine allegedly wrote:

... it appeared an unworthy thing that in the celebration of this most holy feast we should follow the practice of the Jews, who have impiously defiled their hands with enormous sin, and are, therefore, deservedly afflicted with blindness of soul ... Let us then have nothing in common with the detestable Jewish crowd; for we have received from our Savior a different way. (Eusebius, Life of Constantine, III, chapter XVII, quoted in Schaff)

Constantine elected the practice which churches in Rome followed: the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. The later law codes under Theodosius I (r. 379-395 CE) and Justinian I (r. 527-565 CE) claimed that Constantine also created legislation against the Jews: Jews could not seek converts, were forbidden to own Christian slaves, and could not circumcise their slaves. Christians who converted to Judaism were to receive the death penalty. On the other hand, Jewish clergy were offered the same tax exemptions as Christians.

Constantine is often credited with determining the date for Christmas, too, although no edict has survived. Christians in Rome celebrated the event during the festival of Saturnalia in December. 25 December was also the birthday of Sol Invictus and Mithras and may have been utilized in attempts to unify these festivals. From an ancient calendar, we know that in the year 336 CE, at least in Rome, the celebration was established on 25 December.

The first 300 years of Christianity were dominated by the existence of multiple communities that articulated their beliefs in various ways; until Constantine, there was no central authority to determine dogma and ritual. In the 2nd century, the writings of the Church Fathers produced what eventually became Christian dogma. Many of the same ideas are evident in Constantine’s letters and speeches. The same Church Fathers had invented the concept of orthodoxy (correct belief) against other views, which were considered heresy. Under Constantine, heresy was defined in relation to these earlier Christian views. The property of heretics was confiscated, and their execution was by burning at the stake. The Church Fathers had determined that only the gospels of Mark, Matthew, Luke, and John contained the correct teaching, against the Gnostic gospels, and many scholars believe those four, found in the later Codex Sinaiticus (an early version of the Bible in the 4th century CE), became official under Constantine.

Christian Art & Architecture

Originating as a sect of Judaism, Christians initially held to the ban on images. During the reign of Constantine, Christian art began to flourish, particularly with the craft of mosaics. As patron of the Church, Constantine provided funds for artists and artisans and allegedly had the imperial symbol of either the chi-rho or the cross painted on the legions’ shields.

Christian tradition credits Constantine with creating the cross as a religious symbol, after outlawing crucifixion as a means of execution. No official edict has survived; it comes from the later Christian historian, Salminius Hermias Sozomenus (400-450 CE), who claimed:

He regarded the cross with peculiar reverence, on account both of the power which it conveyed to him in the battles against his enemies, and also of the divine manner in which the symbol had appeared to him. He took away by law the crucifixion customary among the Romans from the usage of the courts. He commanded that this divine symbol should always be inscribed and stamped whenever coins and images should be struck, and his images, which exist in this very form, still testify to this order. (Sozomen, Ecclesiastical History I, 8)

As emperor, Constantine continued the standard practice of building monuments and basilicas (public buildings). Their characteristic shapes helped form the standard of churches, with a nave and apses for side altars. In Rome, Constantine built the first basilicas of St. Peter and St. John in Lateran. His new imperial city, Constantinople, was famous for its imperial architecture.

In 325 CE, Constantine’s mother, Helena, made a pilgrimage trip to Jerusalem. There she claimed to have discovered the sites associated with Jesus, including the "true cross". Constantine then constructed The Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem and The Church of the Holy Sepulcher (housing the tomb of Jesus) in Jerusalem.

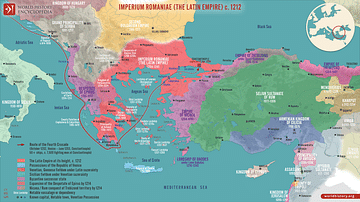

Constantine also built the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. In his will, he wished to be buried there as the thirteenth apostle. The church survived 1204: the sack of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade but was later destroyed.

Despite the skeptics, there is no doubt that Constantine's combining of church and state contributed to the further growth of Christianity and the evolution of its theology. Constantinople became the seat of the Byzantine Empire which ruled throughout the Middle East until the conquest of Islam in 1453: the fall of Constantinople.