Dion is located at the foot of Mount Olympus in the north of Greece, in what would have been ancient Macedon. It takes its name from the most important Macedonian sanctuary dedicated to Zeus ("Dios” meaning "of Zeus”). Legend claims this is the site where Orpheus died and was buried.

Dion features intermittently in the Classical period, notably as the first city reached by the Spartan general Brasidas (d. 422 BCE), who was travelling northwards against the Athenian colonies in Thrace during the Peloponnesian War (c. 431-404 BCE).

However, the site was most important under Macedonian authority, notably Philip II (r. 359-336 BCE) and his son, Alexander the Great (356-323 BCE). Both kings celebrated victories here, and it was at this sanctuary that Alexander conducted sacrifices before his campaign into Asia in 334 BCE.

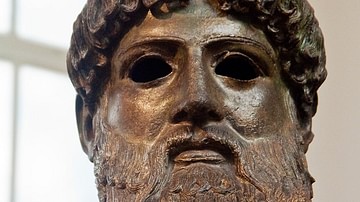

The site was famous in antiquity as the location of one of the sculptural masterpieces of Lysippos (c. 390-c. 300 BCE). At Dion, the 25 bronze mounted companions, who had fallen fighting for Alexander at the Battle of the Granicus in 334 BCE, were displayed. These were taken as spoils to Rome by Metellus Macedonicus (d. 115 BCE) in the mid-2nd century BCE (c. 147 BCE). During the Hellenistic period – after the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BCE – a city was established adjacent to the sanctuary. This city took on an increasingly monumental character under successor kings.

The city was taken by the Romans in 169 BCE but continued to flourish. It was refounded as the Colonia Julia Augusta Diensis in 31 BCE by Octavian (63 BCE-14 CE). Octavian would soon go by the name of Augustus, the first emperor. Dion flourished during the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE when the rapid succession of soldier emperors – particularly during the period known as the Crisis of the Third Century – had a particular interest in the romance of Alexander the Great.

Dion endured into the late Imperial period. It was the seat of a bishopric in the 4th and 5th centuries CE following the spread of Christianity. The site was eventually abandoned as a result of environmental catastrophes.

The remains of Dion can still be seen. The sanctuary extends beyond the walls of the city, traces of which are well preserved in places. To the west of the site, there is a theatre, stadium, and an odeion. Evidence recovered from this area indicates a rich variety of cults, including Dionysus, Athena, and Cybele. Within the city, there is evidence of shops and a bathing complex. The local museum, in the nearby village of Malathria, houses many of the smaller finds. These include funerary monuments, cult statues, and architectural fragments. There are also impressive Macedeonian chamber tombs in the vicinity of Dion.

Odeum

The Roman Odeum of Dion was built in the late 2nd century CE as part of the large Great Thermal Baths complex. An attached series of shops and a public latrine separated the Odeum from the main street. The small, covered theatre was used for concerts, plays, pantomimes, poetry, and musical performances. It had seating for around 400 spectators. Its exacting construction shows the architect was concerned not only with aesthetics but with superior acoustics. Overall, the southeast-facing semi-circular cavea measured approximately 25 metres (82 ft) with ten rows of seating resting on eleven vaulted sections.

Excavations of the Odeum were carried out in the 1970s and 1990s. More recently, extensive restoration work has seen the reconstruction of the cavea and the fallen columns erected. The attached latrines are well preserved, with the seating and floor mosaics visible.Two 1.5 metre (4.9 ft) thick concentric walls formed the koilon with arches supporting the tiered seating. At the upper perimeter of the koilon, a row of narrow columns supported the wooden roof and may have been used for sliding closures to improve acoustics. Behind the orchestra area, four monolithic columns formed a simple skene for theatrical scenery. The covered theatre was enclosed within a rectilinear building measuring approximately 28.5 x 19.5 metres (93.5 x 63.9 ft). The Odeum was badly damaged by earthquake, followed by an extensive fire in the 3rd century CE.

Great Thermal Baths

The Great Thermal Baths were the largest and most lavish baths built in Roman Dion. They were built in the late 2nd century CE and abutted the southern city wall. Entrance to the baths was via a narrow forecourt from the east. The bathing complex was arranged around a large, central reception hall decorated with a beautiful mosaic floor. Busts and portraits of local patrons and important citizens were displayed in the reception hall, including the local philosopher, Herennianos. The reception hall opened onto the changing room. A large heated area for hot and warm baths dominated the southern portion of the building. The extensive underfloor hypocaust heating system and false walls made of terracotta pipes allowed hot air to circulate throughout the rooms.

The marble pool of the frigidarium is located on the western side of the reception hall. The northern wing of the bathing complex was dedicated to social activities and relaxing. It was decorated with marble columns and mosaic floors. One room was reserved for use by members of the cult of Asklepios. A sculptural group of statues was found here depicting Asklepios and his family, including wife, Epione, his sons Machaon and Podaleirios, and his daughters Hygieia, Panakeia, Aigle, Aceso, and Iaso. The sculptures date to the late 2nd century CE but mimic the style of the early 4th century BCE models. A small covered theatre (an odeum) was built as part of the bathing complex and formed its western wing, along with a series of shops and a public latrine. The baths were only in use until the late 3rd century CE when they were badly damaged by earthquake and flood.

The entire bathing complex is beautifully preserved. Access over the standing walls is provided via a raised walkway to show the mosaics and extensive hypocaust heating system. Mosaics include intricate knotwork with scenes of aquatic beasts, floral motifs, a horned bull, and geometric rosettes.

Dion Hellenistic Theatre

The Hellenistic Theatre was built into a natural hill during the 3rd century BCE. It underwent several phases of modification during the reign of Philip V (r. 221-179 BCE) and the Roman period. Theatrical games were held at the theatre, including the nine-day festival in honour of the Nine Pierian Muses.

The northeast-facing cavea extended slightly beyond a half-circle. Its complete diameter is uncertain due to poor preservation and later robbing of material from the theatre. The seats were made of large mud bricks. These were clad with marble before the Roman period. The orchestra was made of beaten earth with a diameter of about 26 metres (85.3 ft). An open stone gutter surrounded the orchestra with small bridges located at the central cuneus and the north parodos.

An underground passage linked the stage with the centre of the orchestra. It included a subterranean staircase (known as "Charonian Steps"), ideal for sudden appearances on stage. The skene was elevated above the orchestra with a colonnaded façade. A wide proscenium with flanking wings housed the mechanical stage equipment. Two large flanking pillars supported the movement of large mechane or cranes. The rear theatre buildings feature a Doric entablature with roof tiles in the Laconic style. Fragments of coloured marble from the proscenium show it was highly decorated.

Much of the stonework from the Hellenistic Theatre was robbed during the Roman period and reused in the construction of the Roman Theatre. Excavations began in the 1970s, and the theatre has been restored to show its size and arrangement. Since the 1990s, the theatre has hosted performances during the Olympus Festival.

Dion Dionysus Villa

The Dionysus Villa is a sprawling, luxurious private residence dating to the 2nd century CE. The villa complex was originally built with five interconnecting tetrastyle courtyards and atrium gardens. It was modified in the 3rd century CE to divide it into three connected villas. The complex of buildings includes a bathhouse, shrine to Dionysus, shops, and an array of domestic rooms.

It is named for a beautiful floor mosaic found in 1987 in the banquet hall. The central panel of the mosaic is 2.2 x 1.5 metres (7.2 x 4.9 ft) in size and made of polychromatic tesserae tiles. It depicts the triumphal Epiphany of Dionysus. The god is shown riding in a chariot, accompanied by a mature Silenus (companion of Dionysus). Two panthers and two centaurs draw the chariot. The centaurs carry a crate of wine and the hidden, sacred symbols of the Dionysus cult. Surrounding the central panel is an elaborate guilloche border with six smaller panels showing masks. These include Dionysus, his enemy Lycurgus King of Thrace, satyrs, Silenus, and the nymph Thetis. The mosaic covers 100 square metres (1076 sq ft) and has complex geometric patterns.

The central villa was built around a large tetrastyle courtyard that opened onto a series of formal entertaining rooms. These rooms included the elaborate triclinium that was decorated with the famous Epiphany of Dionysus mosaic. Bronze fittings from wooden reclining couches (klinai) were found in the room, as well as bronze horseheads, an image of Herakles, and a satyr. An exedra (niche with raised seats) opening off the courtyard contained portrait busts of Faustina the Younger (c. 130-175 CE) and Agrippina the Elder (c. 14 BCE-33 CE). Another room had fragments of a marble Nike. A statue group depicted four Epicurean philosophers – a bearded teacher with a scroll, alongside his three students.

The south villa featured two tetrastyle courtyards. The front courtyard included a well and cistern. A corridor led to the extensive private bathing complex. The larger, rear courtyard gave access to a series of sumptuous rooms, including one with an exedra and a floor mosaic of Dionysus. This same room also had a marble statuette of Dionysus holding a cornucopia and a marble statue of a soldier holding a shield adorned with Medusa’s head.

The entrance to the bathing complex was either via the street or from within the villa. The bathing rooms were arranged around an open courtyard. Three large rooms to the north were ornate reception rooms with mosaic floors. The large pool of the frigidarium was located to the east in an apsidal room. It contained a marble Hercules in the Farnese style. The southern wing consisted of a series of interconnected warm and hot baths with hypocaust flooring. Shops ran along the façade adjoining the street.

The sprawling complex is well preserved with much to see, including standing columns around the atrium courtyards and decorative elements. A raised walkway provides access over some sections for a better view of the mosaic floor panels. Many of the fine statues can be seen in the museum. An extensive recovery and restoration project between 2015 and 2017 saw the complete removal of the famous mosaic to a dedicated building on-site to preserve it. It can now be seen in the Archaiothiki, west of the museum.

Episcopal Basilica

The early Christian basilica was first built in the 4th century CE along the road leading to Mount Olympus. It was expanded in the 5th century CE. In its first phase, the church was built as a three-aisled basilica with a narthex. The entrance was from the western end. Remaining fragments of wall fresco show it was decorated with murals, including architectural motifs. The floor featured a series of geometric mosaics with the central aisle in marble inlay. To the west of the main church was a triconch baptistery. The early basilica was destroyed by earthquake at the end of the 4th century CE.

The arrangement of the Christian basilica can be seen, including the narthex, two phases of the apsidal eastern end, and baptisteries. A raised walkway gives access over the atrium to see the remains of the fountains. Fallen architectural elementals, columns, and inscribed stones lay scattered through the area.A new building was constructed over the ruins in the 5th century CE. It was vastly extended to incorporate a new baptistery. A monumental propylon entrance was constructed from the main road via a porch. This led either to the main church to the east or onto a western atrium. The atrium had colonnades on three sides around a central fountain. Beyond the western colonnade was the new baptistery with a masonry fountain in the shape of a Maltese cross within a paved octagon.

Dion Hydraulis Sector

This large building complex has been named the Hydraulis Sector after the bronze hydraulis (water organ) that was found near the large eastern hall. The hydraulis is a musical instrument invented in the 3rd century BCE by the Greek engineer Ktesibios (285-222 BCE) of Alexandria. It uses water and air to produce sound.

The water organ found at Dion was crafted in the 1st century BCE and is the oldest known example in the world. It measures 1.2 metres (3.9 ft) high and is 0.7 metres (2.2 ft) wide. It has two sets of connected bronze pipes – one row of 24 wider pipes with a diameter of 1.8 centimetre (0.7 inches) and the other of 16 narrower pipes of less than one centimetre (0.39 inches) in diameter. Each pipe is decorated with silver rings to give the appearance of cane. Bronze plates join the two rows of pipe. These plates are decorated with strips of silver ornamented with flowers and guilloches, along with elaborate polychrome glass tiles worked in the millefiori style.

Excavations of the complex found a rich assortment of artefacts that appear to have been left for repair within a metal-working shop. These included precious vessels, bronze lamps, and medical instruments. One instrument is a 1st century CE bronze dioptra (gynaecological instrument) matching those found in Pompeii.The function of the large complex is not known. The two-storey building consists of a large number of rectangular rooms arranged around a central colonnaded courtyard. A brick stairway connected the two levels. This upper level may have been added in the 4th century CE. The western wing of the complex opened onto the main cardo (north-south road) as a long colonnaded stoa or covered gallery.

The large insula block of the Hydraulis Sector can be freely explored. The colonnaded façade that fronts onto the main road is clear, as well as the arrangement of assorted rooms around the central courtyard. The bronze lamps and other artefacts are on display in the on-site archaeological museum. The carefully restored hydraulis is also on display.

Eastern Vespasians

The public latrines in this part of the city were also used by guests at the praetorium. The latrines were located along the smaller eastern road directly opposite the inn. Public latrines were often referred to as "Vespasians" in retaliation to the tax imposed by emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE) on the collection of urine from public toilets.

The Eastern Vespasians are well preserved despite the encroaching marshland. While the marble seating is partially collapsed, it is still possible to see the arrangement of the toilet, the individual latrine holes, and drainage system. The four stone column bases mark the position of the central pool. The entrance was via two side vestibules on the western wall (opposite the praetorium). Between these entrances was a constantly flowing water fountain. The latrines were spacious and arranged around a square atrium with a central pool. The roof was supported by four wooden columns on stone bases at each corner of the pool. A deep water channel ran around three sides of the room with the marble lavatory seat fitted above. A gutter below each seat carried away wastewater.

Praetorium

The praetorium was a guesthouse used by visiting state officials as well as ordinary travellers. At Dion, it was located near the forum at the junction of the main cardo and the road leading to Mount Olympus. A Latin inscription recording the construction of a “praetorium with two tabernae” allowed this building to be identified. The main entrance was from the southern side alongside three shops that fronted the side street. The entrance led onto a large courtyard with a central well and a luxurious triclinium. Five private bedchambers were located along the eastern side of the courtyard. On the western side was a series of stables for draught animals. Adjacent to the stables were two large inns with an antechamber. In the largest of the tabernae rooms, excavators found large storage jars, many clay cups, and hanging lamps.

The walls of the praetorium remain standing to over a metre (3.2 feet) in height. The surrounding paved roadway, large court, and series of surrounding rooms are clearly visible. Pottery from the building is on display in the on-site archaeological museum.

Polygonal Building

The Polygonal Building is located at the intersection of the main cardo and the decumanus (east-west road), which led to the western city gate. The building is part of a larger complex that has not been excavated, and its function is not known. However, it was first thought to have been a palaestra due to a mosaic depicting wrestlers that was found in one of the rooms.

The unusual Polygonal Building covers an area of 1,400 square metres (15,069 square ft). The external walls of the building are roughly square, with the rooms arranged around a central twelve-sided courtyard. A portico surrounds the central court to give access to each of the connected rooms. The entrance is from the south on the street opposite the forum baths.

On the north and south are matching oblong rooms with apsidal ends and paved floors. The southern room featured the mosaic of the wrestlers. A marble table was found in the northern room. Exedras open from the central court on the east and west sides. The east exedra is a large semi-circle, while the west exedra is smaller and rectangular. At each corner, between these various formal rooms, are smaller ancillary rooms.

The walls of the Polygonal Building remain standing to several metres in height. The shape of the courtyard and its unusual arrangement of rooms is clear. Some architectural elements remain on display throughout the complex.

Roman Forum

In the late 2nd century CE, the Roman Forum was built over the top of the Hellenistic agora. The new forum consisted of a rectangular paved courtyard measuring 58 x 68 metres (190 x 223 ft). The Roman Basilica formed the eastern border of the forum. On the other three sides, it was surrounded by porticoes. The northern portico gave access to the public forum baths. To the west of the forum was the Augusteum. The southern portico opened onto a series of shopfronts.

The Roman Basilica was used for commercial and banking activities. It was a long covered stoa of three aisles formed by two rows of Doric columns. Doors at its southern end gave access to the spacious curia where the ruling decuriones of Dion met for assembly.

The Augusteum was a single-roomed temple dedicated to the worship of the imperial family. It had a Doric façade and a mosaic floor raised above the level of the forum. Its walls were painted to mimic coloured marble. Excavations have uncovered fragments of large male statues that originally stood on a semi-circular pedestal.

Sections of paved courtyard and the surrounding portico wall show the arrangement of the forum. Decorated marble architectural elements remain scattered throughout the area. In the Augusteum, a section of painted wall remains visible.

Cardo and Monument of the Shields

The main cardo of Dion was a wide street on a north-south axis that connected the city centre with the nearby religious sanctuaries. The original street was laid out in the late 4th century BCE. In the 3rd century CE, it was paved in large conglomerate stone from nearby Mount Olympus. At this time, its width was reduced to 5.6 metres (18.3 ft) with a stepped kerb. The southern portion of the street was lined with colonnaded porticoes.

The rising water table and subsequent flooding throughout the city in the late 4th century CE required changes to the inner city’s eastern wall. Rubble masonry and building material from earlier buildings were reused to construct a new wall alongside the cardo. One section of wall that runs along the western side of the main street is decorated with alternating panels of shields and breastplates – known as the Monument of the Shields. These panels come from a frieze originally carved in the 4th century BCE for an unknown monumental Hellenistic building. The wall and frieze formed the eastern façade of the basilica in the Roman forum.

The main cardo is well preserved, with the paving and kerb visible for much of its length. Wheel ruts from extensive wagon traffic can be seen along the street. The Monument of the Shields remains standing for several metres. Other sections of rebuilt wall show the reuse of column drums and other architectural elements.

Forum Baths

The Forum Baths were one of several new bathing complexes constructed during the Roman period. These baths went through several transformations between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE. The baths were located immediately north of the new Roman Forum, at the intersection of the main cardo and decumanus.

Access to the baths was via the north porticus of the forum or a monumental entrance from the main cardo. This entrance led to a large reception hall with floral wall paintings and mosaic flooring. Steps led down to the bathing chambers, including frigidarium, tepidarium, and caldarium. False walls between the heated rooms were made with successive layers of terracotta piping that worked as air ducts to warm the walls and floors.

The lower walls of the bathing complex remain standing and show the arrangement of the building. Sections of marble cladding and tiled flooring remain in several areas. Large sections of the hypocaust heating system and terracotta pipes can also be seen.

Baths of the Main Street

Several bathing complexes were built in Roman-era Dion during the extensive rebuilding project of the late 2nd century CE. The Baths of the Main Street were located on the eastern side of the marble-paved cardo, opposite the Monument of the Shields. Two entrances led into the baths from the street via a covered walkway. These both opened onto a large open hall that dominated the western portion of the bath complex. A smaller reception room is located to the south of the building. It featured two marble columns, marble-clad walls, and a mosaic floor. The latrine and frigidarium, with its large swimming pool, are located in the north of the building. The eastern section of the building contained a series of three rooms for warm and hot baths. In these rooms, the hypocaust heating system can still be seen with a series of brick arches and pillars beneath floor level. The furnaces are located behind the bathing rooms to the east.

The lower walls, including marble cladding and floor decoration, remain to show the arrangement of the bathing complex. Fallen marble columns, sections of tiling, and large areas of the hypocaust heating system and terracotta pipes can also be seen.

Houses of Zosa and Leda

These two private houses were located in the southeastern corner of the ancient city. Only a narrow road separated them from the southern city wall. Both houses were built around the 2nd century CE and lavishly decorated.

The House of Zosa was a spacious home with an unusual layout. Most of the rooms were decorated with fine floor mosaics featuring geometric motifs or bird scenes. The owner of the home is proclaimed in an inscription ΤΩ ΕΥΤΥΧΙ ΖΩΣΑ ("for fortunate Zosa") on a mosaic depicting a grouse on a branch. Another mosaic shows brightly coloured birds on the rim of a kantharos jug. The main central hall contains an unusual rectangular feature of three marble-lined cists. The southeastern room had a small shrine within a niche alcove with a cult statue displayed on a pedestal.

The neighbouring home is known as the House of Leda, named for an intricately carved marble table support with a representation of Leda embracing Zeus in the form of a swan. This table support was found in situ in the formal reception hall of the home. The sculpture was crafted in 2nd century neo-Attic, copying a late Hellenistic model. Two other lavish 2nd-century CE marble table supports were also found set on the southern wall – one depicting Dionysus relaxing alongside a panther with grapevines twirling around the base and the other with the head and foot of a lion. The home was further decorated with marble busts and small statues, including a 1st century CE bust of a young boy with his curled hair arranged in a top-knot in the distinctive style worn by devotees of the goddess Isis.

The lower walls to about a height of one metre (3.2 ft) remain and show the arrangement of the spacious homes. Some of the geometric mosaic can also be seen. Replicas of the marble table supports are displayed in the house. The original statues and the mosaic with inscription can be seen in the on-site museum.

Sanctuary of Isis

Located alongside the sacred springs of the river Vaphyras, the earliest sanctuary at this location was dedicated to Aphrodite, Artemis, and divinities associated with fertility and motherhood. The river Vaphyras was also worshipped as a deity. According to legend, the river once ran entirely on the surface and was known as the Helikon. When the women who killed Orpheus went to wash the blood from their hands, the river refused them – it wanted no part of his murder. To not become tainted, the river disappeared underground for 22 stades (approximately 4 kilometres or 2.5 miles) and returned to the surface as Vaphyras.

The Sanctuary of Isis was built during the 2nd century CE. The main entrance to the complex was from the east onto a large courtyard. A secondary entrance with an elaborate propylon was also located to the north. Running roughly east-west through the centre of the courtyard, a long, paved channel with low side walls represented the river Nile. It led directly to the altar and the main temple of Isis Lochia, who protected women following childbirth. The altar was decorated with two marble bulls representing the Egyptian god Apis.

The main temple was a four-columned prostyle temple with a wide porch at the same level as the courtyard. Beyond the columns, a series of stairs led to the raised temple with a pronaos and central cella. The marble steps feature votive slabs engraved with the footprints of pilgrims. The main temple was flanked by smaller ones.

Worship of Aphrodite Hypolympidia (under Olympus) continued in a small nymphaeum to the north (right) of the main temple. The stepped water basin in the centre of the room would have reflected the image of the cult statue that stood within a niche on the western wall - the statue dates to the 2nd century BCE. To the south of the main temple was a one-room shrine dedicated to Isis Tyche (Fortune). It was built of brick with a semi-circular apse on the rear wall to house the cult statue, which overlooked an elongated oval pool. The southern wall featured a series of stepped alcoves. The northernmost precinct enclosure included a stoa, a dormitory for initiates, a hypnotherapy room, and a hall for displaying statues of benefactors.

The sanctuary of Isis was destroyed by flood in the 4th century CE following an earthquake. It remained undisturbed and buried in mud until its recent excavation. A large number of artefacts and statues remained in situ and have been conserved. The sacred springs continue to flow inside the shrines dedicated to Isis Tyche and Aphrodite. The rising water table means the entire sanctuary is partially filled with water. Although the marshy ground makes access difficult, a raised walkway provides access for visitors.

The temples and northern buildings all remain standing to several metres in height. Several columns lie visible in the water or have been raised in situ. Replicas of the statues of Isis Tyche and Aphrodite stand on their pedestals within the curved apse and the nymphaeum. Other votive statues, inscriptions, and dedicatory plaques are displayed throughout the ruins. Along the northern wall, a statue honouring the benefactor Loulia Frougiane Alexandra is on display. Additional finds from the sanctuary can be seen within the on-site archaeological museum, including a relief showing Demeter holding a sheaf and sceptre dedicated to the triad Serapis-Isis-Anubis.

Sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos

Entrance to the Sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos was along a processional sacred way lined with inscribed dedications to the god, often as small columns topped with marble eagles. A square temenos wall surrounded the main temple. The single-roomed temple cella was surrounded by a colonnade. The floor was decorated with mosaics, including a white bull and a double axe. The cella was decorated with images of crows. The cult statue was displayed on the northern cella wall. This finely crafted Imperial-era statue was found within the temple and remains almost completely intact. Zeus is depicted seated on his throne and crowned with a pediment. He holds a thunderbolt in his right hand and a raised sceptre in his left. Also displayed within the temple was a marble eagle that stood with outstretched wings gazing towards Zeus. A statue of Hera found nearby likely stood on the same pedestal as Zeus.

A cistern and water basin are located on the western side of the main temple. In front of the temple stands the main altar alongside a stone block with a metal ring used to tie animals awaiting sacrifice. Within the precinct surrounding the main temple were several long stoas and various rooms used for cult worship. Inscribed votive offerings from throughout the sanctuary date to Hellenistic and Roman times, revealing information about the sacred rites associated with Zeus Hypsistos, including the Roman Nonae Capratinae, held annually on July 7 each year. During this feast and festival, women assisted in the sacrifices, and female slaves were given temporary liberties.

The Sanctuary of Zeus Hypsistos was first excavated in 2003. Today, the ground around the main temple is marshy and difficult to access. The sanctuary walls and the foundations for the main temple and altar remain clearly visible, although the rising water table makes access difficult. Replicas of the cult statue and several votive statues from the sanctuary are on display. Many finds from the sanctuary are also displayed within the on-site archaeological museum.