Carsulae in Umbria, central Italy, was founded c. 300 BCE and only became a prosperous urban centre after it was connected by the Via Flaminia towards the end of the 3rd century BCE. It was granted the status of municipium and acquired a range of impressive civic buildings, including a theatre, amphitheatre, forum, temples, and baths.

The city was eventually abandoned for unknown reasons, possibly because of landslides, and escaped later redevelopment. Roman Carsulae was raided in later periods as a source of stone for new buildings, but substantial ruins of important structures remain. These include the basilica, the theatre dating to the reign of Augustus (27 BCE-14 CE), two temples, the baths, the forum, and an impressive arch over the Via Flaminia.

Tabernae

This series of connected buildings were used for trade and commercial purposes. They were among the earlier buildings in Roman Carsulae and date prior to the Imperial period. Initially, four large rooms with arched entrances were located on the lower level. A second storey leading to the forum terrace was accessible via a stairway on the southern side. The ground-floor rooms had vaulted ceilings and stone counters for the display and sale of goods. The most northern room was converted to suit the construction of the monumental arch over the Via Flaminia. The arch was built as a tetrapylon, or four-columned building, with stairs leading up from the southern roadway to give access to the upper terrace level and the twin temples of Castor and Pollux.

The vaulted rooms were several metres in height, including the arched entrances. The remains of the door hinging, the threshold, and doorstep can be seen. The southern stairs also remain, showing access to the upper level. The tetrapylon has been partially reconstructed around the remains of the stair leading to the forum terrace.

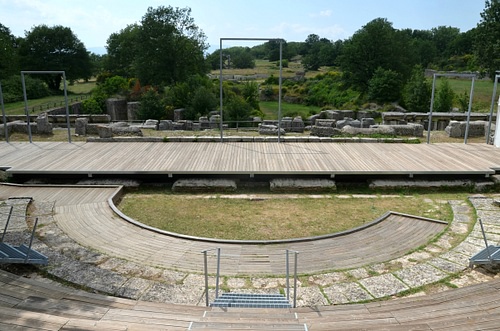

Theatre

The Theatre at Carsulae was built entirely above ground level. It rested on a solid concrete fill with the upper cavea built on a structure of 15 wedge-shaped barrel-vaulted chambers. Access to each chamber was via a vaulted ambulacrum that surrounded the lower cavea and provided a foundation for the upper cavea. Two staircases provided access to the upper level within a rectangular projection off the rear wall of the cavea. Overall, the cavea was almost 63 metres (206 ft) wide, with the seating arranged in four wedges. The seating faced west, directly aligned with the main entrance of the later amphitheatre. The number of seating rows is unknown as nothing is preserved beyond the cavea’s substructure.

Visitors can explore the remains of the theatre, along with the modern reconstruction. The substructure of the cavea is beautifully preserved, and visitors can see the construction method used to form the barrel-vaulted chambers beneath the theatre seating. A modern reconstruction in timber shows the arrangement of the lower cavea. The unusual arrangement of the rear rectangular stairway can also be seen. A wooden stage has been erected to view the foundations of the scenae or main scene area.The orchestra was 20.5 metres (67.2 ft) in diameter and paved in limestone slabs. It was surrounded by a walkway over a drain which connected to a large barrel-vaulted cistern that ran alongside the postscaenium wall. A marble wall separated the walkway from the seating area. The stairs accessing the orchestra were made of pink stone and limestone.

The front of the stage was 35.6 metres (116.7 ft) long, built of brick with a marble veneer, and decorated with three rectangular niches. The main scaenae frons featured a shallow, central curved niche almost eleven metres (36 ft) wide, flanked by rectangular hospitalia. The outer façade of the theatre consisted of 22 piers in opus quadratum, each 1.2 m² (12.9 sq ft) and standing 2.6 metres (8.5 ft) high, that supported arched openings. A series of eight mast holes supported the aulaeum, or stage curtain, which could be raised and lowered to reveal each stage scene.

Thermal Baths

The thermal baths were first uncovered in 1783 when a mosaic in red and white tile, decorated with marine themes, was discovered. It was removed from the complex, and the site was partially recovered. The baths were briefly uncovered in the 1950s, although no record was made of excavation work. Modern excavations at the baths are ongoing, and only a small portion of the bathing complex has been exposed.

The Roman baths at Carsulae were built slightly apart from the main city and appear to have been used by visitors taking advantage of the healing spa waters rather than for daily bathing and cleansing. The mineralised spring water, rich in calcium, was particularly sought after, and Carsulae was a popular therapeutic spa centre from its earliest days. The baths appear to date to the earliest Roman use of Carsulae with several phases of modification up to the 4th century CE. Much of the material used in later renovations included decorative or stamped blocks and tiles from earlier construction dates. The piecemeal patching and repair work makes accurate dating and reconstruction difficult while excavations are ongoing.

The baths were connected via water channels to the cistern near the Via Flaminia and a newly discovered pre-Imperial-era cistern alongside a pre-Roman polygonal wall south of the city. The complex included an ornately decorated rectangular room that has been interpreted as the tepidarium. Its floor featured the marine mosaic that was removed during the 18th century. Box flue tiles (tubuli) lined the eastern wall to allow heated air to circulate around the walls.

The room’s walls were further lined with thin slabs of marble tile. Large fragments of a glass window pane (measuring at least 35 x 33 centimetres or 13.7 x 12.9 inches), which would have fit into the northwest-facing wall, show the room was also solar-heated. A small room opening on the southern side and an apse located on the north-eastern end appear to have been used as caldaria. Hot bathing pools were heated directly by an underfloor hypocaust heating system. Unusually, the hypocaust pilae appear to have been built as a double-storey. An underground brick arch with a ceramic tiled floor connected the underfloor of the apse with the furnace room to pass hot air directly into the chamber. The frigidarium, or cold pool, was located in a recently excavated room to the east.

Excavations have so far uncovered extensive pottery dating to the full period of occupation, as well as ivory hair pins that would have been worn by a woman, a sewing needle, and small glass vessels. One ivory pin was finely carved with the image of a man’s face.

While excavations continue, access to the baths is periodically restricted. Visitors can see the remains of the rectangular room and apse as well as the hypocaust suspensurae and partially excavated mosaics. Slightly beyond the baths, the water channel and polygonal wall can also be seen.

Twin Temples

The twin temples stood on the southern side of the forum. While the divinities to which they were dedicated is unknown, they are generally interpreted as being temples dedicated to the Gemini twins, Castor and Pollux. Castor and Pollux were traditionally associated with health and healing. Cosma and Damiano were the patron saints of healers and doctors. The temples were built in the 1st century BCE on 1.8 metre (5.9 ft) high podiums lined with pale pink limestone within travertine border. The temples were separated by a narrow corridor paved in a herringbone-patterned opus spicatum. Each matching temple featured a front tetrastyle porch which led to a small naos and main cella. The naos was built distyle in antis, with two central columns between the extending cella walls. Separate wide stairways of 13 steps led to each temple from the forum. The stairs also covered the water drainage channels that surrounded the forum.

The imposing high podiums remain overlooking the forum and have been restored with their original pink limestone façades. The foundations show the arrangement of the naos and cella. Visitors can climb the rear stairway to access the temple podium for a view overlooking the ancient city.

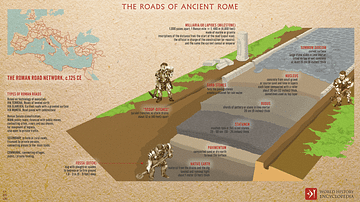

Via Flaminia

The Via Flaminia is the second oldest Roman road after Rome’s Via Appia. It was a consular road, funded by the state, and built c. 220 BCE to link Rome with the northern coastal city of Ariminum (Rimini) over the Apennine Mountains. The road was constructed under censor Gaius Flaminius (c. 275–217 BCE) as a major transport route. It was used primarily for the movement of Rome’s military forces and to supply Rome with grain from the Po Valley.

Carsulae was founded at the same time as the western branch (Flaminia Vetus) between Narni and Forum Flaminii was constructed. Along with its strategic importance (being halfway between Narni and Massa Martana), the fertile soils and freshwater springs made Carsulae a favourable location. The Via Flaminia was restored under Augustus between 27 BCE-14 CE during a period of urbanisation. Augustus oversaw the repaving of the road in the area around Carsulae. The city was then elevated to the status of a municipium and became increasingly prosperous. The new Via Flaminia was built of large, worked limestone blocks. Raised sidewalks (crepidines) on both sides of the road provided additional walking room for pedestrians. New drainage was also added alongside the pavements.

Large sections of the paved Via Flaminia remain visible, and the road is used today by visitors to the archaeological park. In the centre of the ancient town, the raised sidewalk and stone gutter remains in situ. Wheel ruts on the older sections of road show the centuries of use by wheeled carriages transporting goods to Rome.

Amphitheatre

The Amphitheatre and theatre formed a linked complex surrounded by a paved court. The Amphitheatre was built after the theatre in the 1st century CE to stage animal fights and gladiator battles. An epitaph from Carsulae records a gladiator who fought as a pinnirapus iuvenum with a trident and net. The Amphitheatre’s retaining wall dates to the period of the theatre’s construction and may have been used to stage combat events before the Amphitheatre was built. It sat within a natural depression caused by a sinkhole or doline. The ancient Romans were aware of the vulnerabilities caused by the area’s natural terrain and changing hydrological table. They constructed the substructure of the Amphitheatre to withstand ground movement with additional buttresses. The amphitheatre was built in brick and opus vittatum.

The amphitheatre was of modest size, measuring 86.5 x 62 metres (283 x 203 ft). The facades of the shorter eastern and western ends were lined with a series of arches that framed the main entrances into the arena. Gladiators and wild animals likely used the small door at the end of a narrow corridor to access the arena outside of the view of spectators. Additional entrances were located on the longer north and south sides, although these gave access to the upper levels of the seating area.

Only the northern portion of the amphitheatre has been excavated. However, the substructure of the entire oval complex is visible. Visitors can enter the amphitheatre’s arena via the original entrances on the short eastern and western sides. The foundations of the outer rectangular court and earlier retaining wall can be seen, and the immense supporting walls of the amphitheatre itself.

Basilica

The basilica dates to the early 1st century BCE and was used for court proceedings and tribunals. While it was one of the main civic buildings in Carsulae, it stood opposite the forum on the other side of the Via Flaminia. Entrance to the basilica from the main road was via a wide stairway that ran the length of the building. A portico with arched openings gave access to the main room. The large hall measured 30 x 25 metres (98 x 82 ft), and it was divided into three aisles by two colonnades. The wider, central aisle opened onto a connected rear room with an apse at the centre. The attached building on the southern side of the basilica dates to the earliest Roman use of Carsulae and may have been a private residence.

The basilica is poorly preserved, with much of its stone robbed for later construction. The outer foundations of the building remain visible, with the column bases of the colonnades that divided the main hall in situ. The south and eastern portion of the building is better preserved, and the lower walls of the rear apse give an impression of the overall size of the hall.

Church of Saints Cosma and Damiano

The early Christian church was built in the 11th century CE, reusing an existing Roman building. The original Roman building dates to the 1st or early 2nd century CE. The plan of the later church followed the original layout of the Roman structure, which may have been used as a meat market or macellum. The paved Via Flaminia ran directly in front of the building. It was built as a rectangular hall with a rear apse, possibly with internal colonnades in the form of an aisled portico. The southern wall of the church, in particular, shows the Roman arches made of tapered red brickwork that were later filled in. The arches were originally supported by pillars and remained open at ground level. The unmatched stonework courses within the arches show they were added during the church's construction using the original Roman limestone blocks.

The front entrance to the church was constructed reusing Roman materials, including two squat monolithic columns. The simple columns were finished with square plinths instead of decorative capitals. The upper architrave and dentilated cornice are also reused from the original Roman building. In the apse at the rear of the church, the curvilinear window is the original Roman construction.

The Church of Saints Cosma and Damiano beautifully preserves much of the original Roman building. Visitors can see the arrangement of the arches and much of the original decorative work. The carved images of animals and haloed figures on the façade, and the internal frescoes, date to the 11th century CE. Several inscribed plaques and other decorative elements from the Roman city are displayed in the portico entrance.

Cisterns

During the Roman period, natural springs at the base of Mount Martani were diverted towards the town. Five cisterns, two well tanks, and an extensive network of drainage channels and underground aqueducts have been excavated at Carsulae. The most accessible cistern is located on the western edge of the ancient city centre. It was reused during the medieval period as an animal barn. Before the construction of the new visitor’s centre at the archaeological park, it was also used as an antiquarium to display finds from the site.

The largest cistern, which would have been the city’s castellum aquae (primary water storage tank), is located on slightly higher ground, some 100 metres (328 ft) southeast of the theatre. Another long and narrow cistern, consisting of five connected tanks, is located immediately north of the amphitheatre, just off the modern roadway. A fourth cistern is connected to the thermal baths to the south of the city. A small cistern dating to the Republican period was recently discovered during excavations in the town’s northeast.

Each of the cisterns can be seen in varying degrees of preservation. The original walls of the antiquarium cistern remain standing, with the doorways and windows being a later addition. The larger castellum aquae is located slightly outside the main area of the archaeological park. It can be seen just off the walkway on the left side when walking from the car park into the main site.

Curia

A series of two-storey public administration rooms bordered the northern side of the forum. A colonnaded portico ran along the façade of the buildings where the Decumanus ran the length of the forum. The largest building (located on the eastern end) was the curia. It was the seat of the local municipal senate of decurions who were overseen by four magistrates. The curia was built in opus quadratum of limestone blocks alternating with horizontal courses of rubble in opus vittatum and sumptuously decorated with marble. It was built as a long rectangular hall with three arched entrances from the forum. The long, rear wall featured a central apse.

Three smaller rectangular, apsidal rooms were built alongside the western wall of the curia. Their internal walls were lined with marble, and each featured crustae marble pavements. The individual functions of these smaller, neighbouring rooms are not known. However, they were jointly used for related administrative and political activities.

The foundations and some partial lower walls of each of the four buildings can be seen. The rear apses of each building are preserved, along with some sections of marble lining and pavement. The paved Decumanus is well preserved, and visitors can walk the ancient street alongside the administration center of the forum.

Forum

The large public square was located on a terrace at the intersection of the Via Flaminia and the east-west Decumanus. It was shaped as a paved trapezoidal square, with visible remains dating to the modifications made in the Augustan era. Entrance to the forum was marked by tetrapylae. Each tetapylon was 5.5 metres (18 ft) wide with an arch span 3.15 metres (10.3 ft) wide and 7.3 metres (23.9 ft) high.

They were made in opus quadratum with large ashlar blocks of local travertine covered in a façade of pink stone and capped with a decorative pediment. A colonnade ran above the retaining wall and along the eastern side of the forum between the two monumental gateways. The forum was bounded on the southern side by the twin temples standing on their high podium and a long, open portico. On the northern side, the monumental entrance from the Via Flaminia led directly to a series of four rectangular, apsidal rooms, which included the curia and related public administrative buildings. The large temple, located at the far western end of the forum, was identified in 2018 as being the capitolium or main temple dedicated to the Capitoline triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. Excavations in the 1950s found many statue fragments representing the Julio-Claudian family, in particular, a statue of a young emperor Claudius (r. 41-54 CE) from the first years of his reign.

The partially reconstructed monumental tetrapylae mark the entrance to the raised level of the forum. The podium of the twin temples can be seen on the southern side. The best-preserved public buildings are the apsidal rooms of the curia and connected administration offices on the northern side. Only the perimeter walls of the capitolium at the western boundary of the forum have been uncovered, with excavations ongoing. Some sections of the forum’s pink stone pavement can also be seen.

Funeral Monuments

The necropolis located immediately outside the Arch of San Damiano preserves a several monuments dating between the 1st century BCE-1st century CE. The so-called Tower Tomb has been restored to stand at its full height of almost 11 metres (36 ft). Its lower structure is a quadrangular base 4.3 metres (14.1 ft) square and 2.4 metres (7.8 ft) high. Above the base, a hollow cylindrical stone tower with skylights stands 4.6 metres (15 ft) high. The upper pinnacle had two lower steps capped with a tapering conical arrangement. It is decorated with Doric-style embellishments, including a continuous frieze of metope and triglyphs that alternate with carved images of a bull’s head, floral motifs, a dolphin, and urn.

The Tower Tomb has been beautifully restored and stands to its full height, including parts of the decorative Doric frieze. Little remains of the enclosure surrounding the Sarcophagus della Fanciulla. However, the limestone sarcophagus can be seen, and the young girl’s grave goods are on display in the museum. Nearby, a sarcophagus known as the Sarcophagus della Fanciulla was discovered in the 1990s. It was made of limestone with a double kline lid. It contained a lead coffin that housed the remains of a pre-teen girl who was buried with an intricately made gold necklace and earrings. Recent excavations have found that the sarcophagus was located within a rectangular enclosure measuring 8 x 12 metres (26.2 x 39.3 ft). The foundations of the enclosing wall were made in opus caementicium and appear to have supported a two-room building of limestone opus quadratum. The sarcophagus would have been located at the centre of the rear wall of the larger room, which likely contained other burials previously looted. At the centre of the main room, an amphora containing the remains of an infant burial (enchytrismos) was found.

Mausoleum of the Gens Furia

This circular mausoleum dates to the 1st century CE. It was built by cutting into a limestone crag and constructing a terrace wall in limestone opus quadratum. The stone base is approximately 18 metres (59 ft) square. Above the square base, a circular drum-shaped tomb stands four metres (13.1 ft) high with a crowning of crenulations. Inside, six radial walls in opus caementicium would have supported an upper tumulus. The overall height may have been between eleven to 13 metres (36-42 ft).

The tomb likely belonged to the Furia family. An inscription plaque, whose curve matches the mausoleum, records a dedication to the Gens Furia. The inscription honours a father and son of the Clustumina tribe, both named Caius Furius Tiro, who served Carsulae as quattuorvir quinquennalis (four local magistrates who successively served over a term of five years). The plaque was erected by quattuorvir Lucius Nonius Asprenas and two women of the Gens Furia named Secunda and Polla.

The mausoleum remains well-preserved and has been restored. The circular wall of limestone blocks remains standing, including several sections of the upper crenulations. Stairs on the outer wall give access to show the internal arrangements of radial walls. The dedicatory plaque is on display at the Palazzo Cesi in Acquasparta.

Mosaic Domus

Investigations in the area south of the twin temples began in 2017. The excavations in this area are referred to as Saggio E (or Sounding E). Archaeologists uncovered a large residence dating to the first period of monumentalisation in the city during the Augustan era. The luxurious domus features a triclinium (dining room) attached to an enormous banqueting hall measuring 17 x 8 metres (55.7 x 26.2 ft). Its large atrium has a decorative floor in opus scutulatum, a mosaic of black tile with irregular white calcite and polychrome marble insets. The central impluvium was decorated with a mosaic featuring a geometric arrangement of rhombuses. Each of the rooms opening off the atrium was also decorated with ornate mosaic floors, including a main panel of rectangles tightly arranged into squares, with a lower image of an arched portico crowned with merlons.

Immediately south is an internal water basin or tub measuring 3.6 x 1.4 metres (77.4 x 4.5 ft). Another partially excavated room has a mosaic of black and white triangles interconnected to form hexagons. To the west, a room off the peristyle garden courtyard has a complex pattern of orthogonal maze-like meanders formed with alternating black and white squares and hour-glass triangles. Its outer band depicts an isodomic stone wall with a triple-arched gateway and defensive towers, all capped with T-shaped merlons. A series of shops with herringbone-patterned brick floors are located on the northwest side, opening onto the street. Excavations have also found fragments of quality stucco and painted plaster walls. With the exception of ten oil lamps, very few artefacts remained within the domus.

Excavations of the Mosaic Domus and surrounding area are ongoing. The mosaics remain covered for protection while periodic excavation and consolidation work continues. Upcoming seasons plan to excavate more of the domus and an associated hypogeum compartment that is possibly a cistern.

North-East Area C

Preliminary excavations began in 2012 in the large, previously unexplored, open area east of the Via Flaminia and south of the Arch of San Damiano, which marks the northern boundary of the ancient city. The excavations in this area are referred to as Saggio C (or Sounding C). Archaeologists first uncovered a small cistern with a barrel-vaulted roof that dates to the earliest Republican-era occupation of Carsulae. Running immediately alongside the cistern was a well-preserved 14 x 4 metre (45.9 x 13.1 ft) paved section of an early pre-Augustan street, likely one of the northern decumani in use before the realignment of the Via Flaminia. This section of road was preserved by the construction of later buildings and a cocciopesto pavement along its western end. Laying above the paved road was an assortment of debris, including ceramic roof tiles, mortar, and polychrome painted plaster belonging to a later phase of construction. The later buildings included a series of rooms identified as warehouses, and a small semi-hypogean furnace used as a kiln to make thin-walled pottery. Initial construction of these buildings date to the first half of the 1st century CE, with later modifications. The area continued to be used until around the late 3rd or early 4th century.

Excavations in the northeast quarter of the city are ongoing. Visitors can see the exposed pavement, barrel-vaulted cistern, and the foundations of the later buildings.

Northeast Area D

Following successful excavations in 2012 within the large, previously unexplored, open area in the northeastern quarter of the city, an additional trench was opened in 2014. The trench is along the eastern side of the Via Flaminia, halfway between the entrance to the forum and the northern city gate. The excavations in this area are referred to as Saggio D (or Sounding D). A paved area 33 metres (108 ft) long was uncovered that dates to the earliest Republican-era occupation of Carsulae. The road first travels from the direction of the earlier Via Flaminia and then turns to a more easterly direction. This area was modified during the Augustan period when the area immediately north of the road was divided initially into two, and then three, separate warehouse rooms. The original pavement was used to provide access to the separate storage areas. The storerooms were made with limestone walls. Material found within the rooms and paved area includes a huge assortment of pottery, stamped ceramic tile, glass vessels, material from a nearby iron processing forge, and over 60 coins dating to the latest period of occupation during the Theodosian era.

Excavations in the northeast quarter of the city are ongoing, and the angled road with side curbs, water gutter, and extensive wheel ruts can be seen. The three storerooms remain standing to a height of several metres. Consolidation work to conserve the exposed buildings is underway.

Arch of San Damiano

The northern gate to the city, known as the Arch of San Damiano, was built under Augustus between 27 BCE and 14 CE at the same time as the Via Flaminia was repaved. The archway was previously known as the Arch of Trajan after several coins dating to the reign of Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) were found nearby in the 16th century. The city of Carsulae was not fortified and had no city walls. The Arch of San Damiano was built purely as a monumental entrance rather than for defensive purposes. The gate also marked the boundary of the city beyond which were located prominent tombs. The Arch of San Damiano originally consisted of three arched openings. The larger, central arch was wide enough for vehicular traffic, with smaller archways on either side aligning with the raised sidewalks of the street.

A series of three stone steps surrounded the pillars of the central archway. The gateway was constructed with a Roman concrete (opus cementicium) core lined with large ashlar limestone blocks. The blocks fit perfectly and were assembled without the use of mortar. The entire gateway was originally lined with marble slabs. The limestone blocks in the lower portion of the archway were left rough, with smoothed blocks used on the upper portion of the arch (the intrados). While only the central vaulted arch remains, the gate would originally have been surrounded by an abutment and topped with a decorative pediment in the traditional Roman style.

Visitors to Carsulae can walk along the Via Flaminia through the northern gate on the way to the tombs. The central archway remains standing and has been restored to show the full vaulted passageway. The archway has a span of five metres (16.4 ft) wide, with the overall width of the pillars and stepped plinth measuring six metres (19.6 ft). The arch stands 9.2 metres (30.1 ft) high and has a depth of 4.5 metres (14.7 ft) Both the outer stone façade and inner core can be seen, and small holes on the stonework show where the decorative marble slabs were originally fixed.