In this interview, World History Encyclopedia is talking to author Daniel Ogden about his new book The Werewolf in the Ancient World.

Daniel Ogden (Author): Thank you for inviting me!

Kelly (WHE): Of course, we are very excited to have you. Would you tell us a little bit about your new book?

Daniel: This is actually the first book devoted to the subject of werewolves in the ancient world. There is an infinite number of books on werewolves, but there is nothing focussed on the ancient world. The book attempts to understand the ancient evidence in itself and to make sense of the way werewolfism was thought about in the ancient world. But probably the most important contribution is to try to relate the ancient evidence to the more recent evidence, which is the medieval evidence. In the 12th century, there is a sudden upsurge in werewolf stuff in medieval literature, Anglo-French, French, and Norse literature. From then on, there is a continuous tradition. A lot of things change in the early modern period, but nonetheless, there is a continuous tradition. There is a direct link between the modern-day perception and the werewolves back in the 12th century.

The ancient evidence spans from Homer in the 7th century BCE and petered out more or less in about 400 CE. There are 800 years when we have almost complete radio silence on werewolves before they reappear in the 12th century. There are two obvious hypotheses. One is that people in the 12th century were reading the ancient texts and suddenly got interested in werewolves again and restarted it all, which is a perfectly reasonable suggestion. The other, more interesting alternative, is that basically werewolves are deeply embedded in European folklore, and they always were, and they popped up, as it were, for a few centuries in the ancient world, and then during the dark ages, they went underground again, and then popped up more or less as they have been back in the 12th century CE. My argument is that the second hypothesis, the more interesting one, is the right one.

Kelly: So, we do not necessarily know where the myth has originated from. Did it sort of just turn up?

Daniel: No, we do not know where it comes from, and that is also a matter of debate. Some would say is the notion of werewolfism is a projection of ideas about bands of young warriors. It is an unsupported idea that many ancient and indeed more modern societies have this culture of putting transitional youths, maturing youths, into a certain kind of warrior group. In the ancient world, they would have been typically light-armed warriors who are sent off to the borders of a community to patrol the border rather than the heavy-armed, serious soldiers. They would argue that there are many societies that have this sort of young warrior tradition, and werewolves are a way of thinking about young men becoming these sorts of slightly wild, undisciplined, warriors of the margins. I do not believe that myself.

I should say this is a very interesting case, but I do not think that the werewolf grew out of such a social or cultural practice. I think werewolves belong in stories. The home of the werewolf is the campfire horror story, always was. And it is a very striking, powerful idea in itself, which is then used metaphorically by societies in different ways. And indeed, this notion of the youthful warrior band is one sort of thing that the pre-existing notion of the werewolf can be associated with, but there are other things, too. It can be associated, for example, with ideas of disease, and we find both of those in the ancient world.

Kelly: When you are thinking about youths turning into men, there is a lot of other wild animals you could have potentially used that might be more appropriate than wolves. It does not necessarily strike me as something you have to use a wolf for. So, your hypothesis makes a lot of sense.

Daniel: Looking across all the world's cultures, why werewolves, why not were-rabbits, for example? I am very reluctant to talk about the universal features of werewolves beyond the notion of a man turning into a wolf and possibly turning back again. I am reluctant to sort of add any more to our basic definition of the concept. But one thing that is really quite pervasive in the ancient evidence and in medieval folklore, is this notion of 'into the woods'. This phrase 'into the woods' recurs so often. A man turns into a wolf as he runs off into the woods, and occasionally a man runs off into the woods and then becomes a wolf. But there is always this notion of the title of that recent Stephen Sondheim musical, which was very, very well chosen, with being symbolic of our folkloric history.

But I do think that does relate to something fundamental, maybe about the werewolf, that the werewolf embodies this transition or opposition between or negotiation of the civilised human on the one hand and the wild animal on the other. If one gets to that point, one can see that maybe there is some sort of sense in choosing a wolf because there are senses in which wolves might be considered to be the ultimate wild animal. I think another factor is actually that very, very broadly wolves are just about human size, at least the bigger ones can be. It is easy to imagine a transition between a human and a wolf in a way that it is not easy to imagine a transition between a human and a rabbit for example.

Kelly: So, it is like they have chosen the animal the closest to people, and I guess the dichotomy between the civilised man and the wild man goes back so far as well, if you think of the Epic of Gilgamesh, with Gilgamesh and Enkidu who balance each other and they learn something from each other.

Daniel: That is a very good point. Yes.

Kelly: This continuous history, did it alter very much? I know we have had that dark period, but was it just the idea of the man turning into the wolf, going to the woods, and then turning back into a man? Or were there specific points that changed?

Daniel: Well, the notion of the man who recurringly changes into a wolf, I think many people would consider that to be fairly integral to the modern idea of a werewolf.

Kelly: And a full moon?

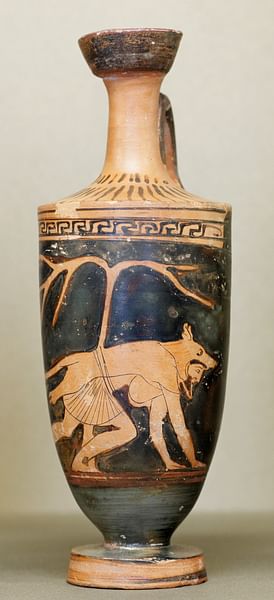

Daniel: Well, that is another thing. That probably starts, as far as our evidence is concerned, in the medieval period. It is not necessarily typical of the way werewolves were thought about in the ancient world. However, the ancient world has one particularly good story about a werewolf, and this is told by Petronius. This story is told in Petronius' novel Satyricon. It is the story of a dinner party given by a nouveau riche person called Trimalchio who is an ex-slave, a freedman. He is completely uneducated but likes to boast of his education and so he gets all these myths wrong. At one point in the dinner party, he and one of his fellow freedmen Niceros exchange campfire horror stories. Niceros' story is about werewolves, so he tells a story, supposedly from his past when he was still a slave himself, and despite being a slave, he had a girlfriend who had a pub. The timing of it is all a bit vague, but seemingly he is setting off during the night to visit her, and his master has a soldier friend staying with him, and the soldier decides to come along for the trip.

They are walking down the road, and it is a road lined with tombs. At one point, the soldier stops to have a pee against the tombs. Niceros is standing with his hands in his pockets and whistling, and when he turns back, he sees that the soldier had actually taken all his clothes off. Then he pees around the clothes in a circle and turns himself into a wolf and runs off. So Niceros goes to the pile of clothes to either retrieve them safely or see what is going on and finds that they have been turned to stone. This peeing in a circle was clearly very magical, and it is clearly designed to protect the clothes. He is terrified now, and he is in a road of tombs anyway, but he imagines himself being attacked by ghosts from all sides as he runs on and finally gets to his girlfriend's house.

The pub is also a farm as well, and his girlfriend tells him he should have been there earlier because a wolf got in amongst the sheep and was butchering them. One of their slaves put a spear through his neck and he ran off with this neck wound. The next morning, Niceros is on his way home, and as he passes the tombs where the clothes were left, the clothes are gone, and there is blood. When he finally gets home, he finds his soldier friend lying in bed with a doctor tending to his neck wounds. At that point, he realised he was a werewolf. You might have thought, well, maybe he might have realised that when you saw him turning to a wolf. But nonetheless, he says that "I refused to break bread with him ever again." I should also say that there is a full moon whilst this is going on, or maybe it says that the moon is brightly shining, so maybe not a full moon.

Kelly: It still references the moon, as if there was an importance in it.

Daniel: Yes, sure. So that is a great story, and there are a number of important ideas. It is quite interesting that the guy says that he only realises the soldier was a werewolf when he finds him in bed with a neck wound. The identifying wound is a very common theme, again, in the later medieval European stories. I think you can see the force of it as a motif already in the ancient world because as I just made clear it is illogical really in the context of the Petronius story. He knew that he was a werewolf when he saw him transform, but it was clearly already such a fundamental, well-established motif that you recognise a werewolf by an identifying wound.

The other point to comment on, of course, is the importance of keeping the clothes safe. The motif is not explained any further in the ancient context, but it does not need to be; it is obvious. Why does a werewolf need to keep his clothes safe? Well, we can easily guess that it is because he needs his clothes if he is going to turn back into a human. That notion of keeping the clothes safe because you depend on them to turn back into a human becomes much more developed in the medieval period.

Kelly: Interesting, because I feel like with werewolves in pop culture nowadays, that does not get explained. In a movie, you see someone just rip through their clothes and turn into a werewolf, and you think, 'okay, are the clothes going to come back when you turn back into a man or do you have to walk home naked'? This does not get explained.

Daniel: Another thing worth saying about that story is that, although we only see him transform into a wolf once, it is clearly assumed that this is something that recurs. And again, that final line, "I refused to ever share bread with him again", is clearly because he fears it might happen again and he might get eaten by a wolf. There is the notion that werewolfism is what you might call cyclical and not a one-off transformation. That is very important in modern ideas of the werewolf.

Kelly: Absolutely, and the fact that he has peed around his clothes suggests he was obviously aware of what he has to do.

Daniel: Yes, and of course, it also implies that the werewolf has magical powers as well. We cannot all just pee around our clothes and turn them to stone.

Kelly: Were werewolves seen as negative or were they revered in cultures? Was it a positive thing to have a werewolf?

Daniel: There are so many interpretations. Already in the ancient world, a number of references seem quite neutral, strangely. Sometimes we hear of sorcerers or witches turning themselves into wolves.

Kelly: So, they were not always men?

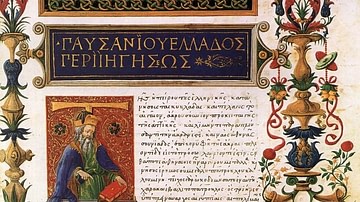

Daniel: The one batch of evidence relating to women turning into wolves is related to witches and that is pretty much confined, I think I'm right in saying, to Latin poetry. Mainly elegiac poetry, actually. Yes, there are female werewolves in the ancient world. There are ostensibly good guys, too. You have to work hard to reconstruct it from references in Pliny and Pausanias. A chap called either Demarchus or Demaenetus was turned into a wolf in Arcadia. The story is told in such an elusive way it is difficult to reconstruct it, but what seems to have happened is - this is my guess anyway - he was attending the sacrifice of Zeus Lycaeus (Wolfie Zeus) on Mount Lycaon (Mount Wolfie) and an enemy, a personal enemy, I suppose, slipped some human flesh into his portion of the sacrifice. The animal sacrifice is shared equally in the usual way, but somehow some human flesh is slipped in, and he eats this, I guess, unknowingly.

It is quite appropriate that actually eating human flesh should be regarded as a way of transforming somebody into a wolf, and this is not the only evidence for that. So having done that, he is turned into a wolf for a period of, I think, nine years, and we are not told how he manages to transform back. I do not know if there was a special way or maybe he just contracted a nine-year curse by eating the flesh. But after that, he becomes a very distinguished Olympic victor, supposedly, and there is no strong indication that he was a bad guy. He seems to be a good guy, and he certainly ended up as a good guy. So, you can have the good werewolf, and I think he was sort of a victim of deceit. That is actually a theme again with those early medieval werewolves as well; they tend to be victims of deceit in some way.

Kelly: That is interesting because I guess when you think about werewolves nowadays, you get both good and bad werewolves in stories, so it is never clear-cut. Thank you so much for joining me today, it has been wonderful chatting with you!

Daniel: Thank you for having me.