Madeira is a group of volcanic islands in the North Atlantic which were colonised by the Portuguese from 1420. The settlement and distribution of land rights on the uninhabited islands was a model the Portuguese Crown would copy in other colonial island groups and in Brazil.

The Madeira archipelago was a handy stopping-off point for ships that plied the trade routes between Europe and the Americas. In addition, with their rich volcanic soil, mild climate, and sufficient rainfall, the islands were exploited for agriculture, especially wheat, wine, and sugar cane, with African slaves being exploited to work the latter plantations. Today, just as in the 15th century, Madeira is most famous for the fortified wine which bears the main island’s name. The islands are today an autonomous region of Portugal.

Geography & Climate

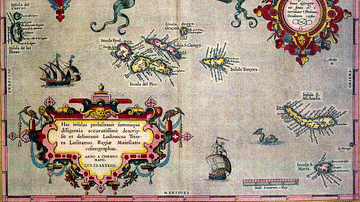

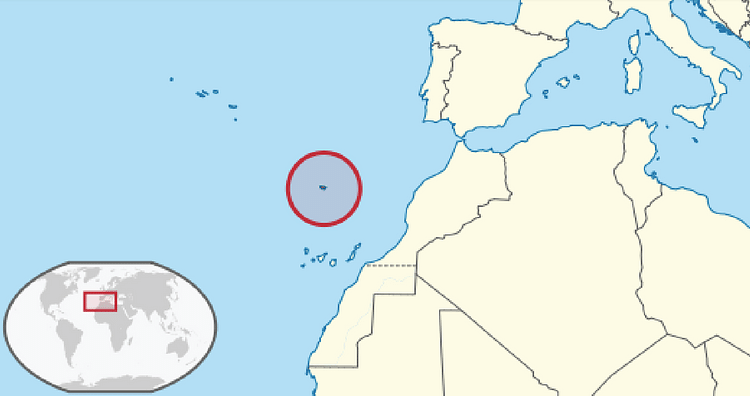

The volcanic Madeira archipelago is located some 800 km (500 mi) from the African coast out in the Atlantic Ocean. The four principal islands of the group are Madeira, Porto Santo, the Desertas islets, and the Selvagens rocks, but only the first two are now inhabited. Madeira is the largest island in the group, 55 km (34 mi) long and 22 km (13.5 mi) at its widest part. The name refers to the plentiful forests on the island. Like the other islands in the group, Madeira is really the top of a submerged mountain and so is dominated by the Ruivo peak which soars 1,861 metres (6,106 ft) above the sea. The advantages of Porto Santo for the early Portuguese settlers were that the island has an area of 42 square kilometres (16 square miles) and mostly flat with few trees, making it ideal for agricultural development, and there are several natural harbours. The climate allows for crops to be grown all year round, which are bountiful thanks to the rich volcanic soil, mild temperatures, and sufficient annual rainfall.

Discovery

The islands were known to both ancient Greek and Roman writers, were possibly visited by Vikings, and were certainly known by Islamic mariners. However, it was not until the early 15th century that the Portuguese, or anyone else, for that matter, took a serious interest in them. Two captains of vessels sponsored by Prince Henry the Navigator (aka Infante Dom Henrique, 1394-1460), who were meant to be raiding the Moroccan coast, landed at Porto Santo in the uninhabited archipelago during a storm in 1418. The accidental explorers quickly realised the potential of the place - one later sailor described it as "one large garden" (Cliff, 71) - and reported back to Henry. In 1419 the Portuguese Crown formally declared possession of the island group, giving its governorship to Prince Henry. The Portuguese military order, the Order of Christ, whose head was Henry, was granted exclusive rights there.

To back up the claim of ownership, an expedition was launched to better explore the islands and find land suitable for cultivation, Portugal then being an importer of grain. At this time, the Portuguese had free reign. A few decades later, Portugal and Spain did squabble over possession of the Canary Islands, but the 1479-80 Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo set out that the latter were Spain’s domain while Portugal took the Cape Verdes, Azores, and Madeiras. There were also some additional vague clauses to the treaty that would cause trouble later such as Portugal’s right to future discoveries in Africa and Spain’s to islands beyond the Canaries, interests which were eventually identified as the Caribbean and even the Americas.

Settlement

The Portuguese Crown partitioned the islands and gave out ‘captaincies’ (donatarias) as part of the system of feudalism to encourage nobles to fund the development of the islands. Nevertheless, the crown still retained overall ownership but gave lordship to Prince Henry and his heirs who in turn distributed estates to their followers. Each ‘captain’ or donatario was given the responsibility of settling and developing their area in return for financial and judicial privileges. The ‘captain’ had his own extensive estate within the territory under his jurisdiction and he could distribute other parcels of land (semarias) to men given the responsibility to clear it and begin cultivation within a set period (first ten but later reduced to five years). These captaincies became hereditary offices in many cases. The model of donatarias would be applied to other Portuguese colonial territories in the future, notably in Brazil.

The first three such governors were knights of the Order of Christ and two were the very men who had arrived on Porto Santo two years before: Tristão Vaz Teixeira, who controlled the northern half of Madeira around Machico, and João Gonçalves Zarco, who had the area around Funchal, founded in 1421. The third captain was Bartolomeu Perestrelo who ruled over Porto Santo. By the mid-15th century, an apparatus of local government was formed with elected officials to govern the burgeoning population. In 1508, Funchal gained official city status.

Many fishermen and peasant farmers willingly left Portugal for a new life on the islands, a better one, they hoped, than was possible in a Portugal which had been ravaged by the Black Death and where the best farmlands were strictly controlled by the nobility. For fishermen, the islands were a handy base surrounded by tremendous possibilities for deep-sea fishing.

Alvise da Cadamosto, a Venetian trader with a license to operate in Madeira, wrote an invaluable record of the islands at that time (as well as Portuguese affairs on the African continent). The account was written around 1468 but describes events of the 1450s and the earlier history of the island:

This island is called the island of Madeira, which means the island of wood because when it was first discovered by the Infante’s men, there was not a palm’s breadth of land which was not covered by immense trees…although it does not possess any port, there are very good anchorages. The land is fruitful and abundant and, although it is as mountainous as Sicily, it is always very fertile and produces 30,000 Venetian stara [4.5 million litres] of wheat each year…The region is very productive and has abundant water and beautiful springs, and there are six or eight small streams that flow through the island…

(Newitt, 56)

The early settlers did sometimes experience troubles despite the Garden of Eden description. Alvise da Cadamosto notes that a fire raged out of control on Madeira which forced all of the first settlers to return to their ships and await offshore for two days until it burnt itself out. At least meat was easy to come across as the island’s wild peacocks, pigeons, and quails had no fear of humans and were easily caught. European farm animals, rabbits, and even Portuguese flora were also introduced to the islands which played havoc with the indigenous species, many of which became extinct.

Sugar Cane & Slavery

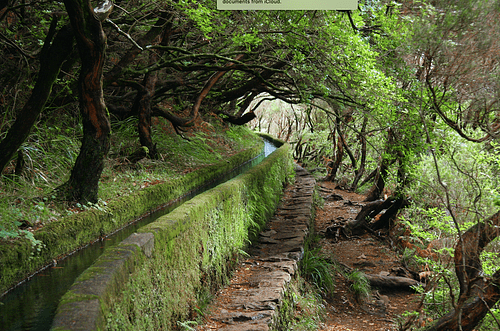

Over time, Madeira’s capacity for agriculture was increased by clearing more and more forest, building stone-walled terraces on the mountain slopes, and creating a system of aqueducts (levadas). Felled trees were made into planks by water-powered mills on the island, and this timber (cedar and yew) was shipped to Portugal and Spain. Around 1455, wheat production was in decline, replaced by sugar cane. This crop was first planted on Madeira using financial backing from Genoese bankers and technical know-how from Sicilian advisors. There were, too, a number of Italian immigrants to the islands as Lisbon at that time had significant communities from the Italian maritime states. Alvise da Cadamosto describes the sugar cane industry:

…Infante had sugar cane planted, which grows to perfection. Different kinds of sugar, amounting to 400 cantara [5,500 litres], are produced, which are useful for cooking or blending, and I understand that they will soon produce a good quantity because this crop is suited to the warm and temperate climate…Many different types of sugar-coated sweetmeat are made to perfection, and wax and honey are also produced though in small quantities.

(ibid, 57)

As the 15th century wore on, sugar began to be exported not only to Portugal but other markets such as the merchants of Flanders and to Constantinople. By the 16th century, exports were booming and the problem was to find sufficient labour to work the plantations. Consequently, slaves were imported from West Africa, sometimes brought by captains sailing from Madeira itself. The number of slaves never outnumbered the European settlers, unlike on other Portuguese islands such as São Tomé. In the latter half of the 16th century, Madeira lost most of its sugar markets to the much larger and more modern plantations in Brazil. Fortunately, the islands had another product to bring the islands more lasting prosperity.

Madeira Wine

Vines were introduced to the island from Crete by the early Portuguese settlers, and these were eventually planted in every valley running down from Madeira's mountain interior. Alvise da Cadamosto gives a vivid description of viticulture on the island:

The new settlers have planted vines and their wines are good and fine. They produce enough for their needs and allow a part of it to be exported. Among these vines are malvoisie grapes from Candia [on Crete], which the infante had brought directly from the Levant. The soil of this island is so good and fertile that the vines produce almost more grapes than leaves and the bunches are enormous, being two palms and I might almost say four palms, long - it is the most beautiful thing to be seen in the world - and there are also black trellis grapes, which have no pips and grow to perfection.

(ibid, 57)

The wine of Madeira was immediately popular with mariners making the voyage from Europe to the Americas, although it was likely not until about 1700 that it began to be fortified. The island group was a common stopping point on the long journey and these sailors then helped spread the popularity of the wine both in Western Europe and in the New World. Fortified by adding a quantity of brandy or sugar-cane spirit (around 10%) to the wine during the fermentation process, the alcoholic content of Madeira is typically 18 to 20% (compared to a strong ordinary wine of 13 or 14%). This high quantity of alcohol allowed the wine to travel well on sea voyages, and another benefit was that it aged extremely well. This is still true of Madeira today and bottles can last for a century or more in cellars. Madeira wines may be sweet or dry depending on the sugar content added and blending. Madeira has a particularly rich caramel flavour thanks to the volcanic soil in which the vines were grown and its unusual ageing process where barrels are not stored in cool cellars but in ‘baking rooms’ or estufas for at least several months. This innovation was a result of mariners better appreciating their wine after the barrels had passed through the tropics on their way to the Americas. Indeed, many barrels of wine destined for England, then a major market for Madeira, were often carried on ships to the Americas and back again as connoisseurs thought this improved the flavour.

Later History

The booming trade in sugar cane and then wine was accompanied by the production of sweet grapes (malvasia), barley, and expensive dyes - red from the resin of the dragon-tree (dracacea draco), known as sangue de dragão (‘dragon’s blood’), and blue from woad (pastel) or litmus roccella (urzela). As time went, on, the islands’ settlements became more European in appearance. The Madeira elite had grown very wealthy, and this was reflected in grand architecture on the island and in luxury imports such as Flemish paintings. The Sé cathedral (1485–1514) in Funchal was built and several monasteries developed, created by the Observant Franciscan Order.

In the 16th century, Portugal had to fight to hold on to its possessions as competition between European powers became more intense. There was also a significant threat from pirates and privateers. A fortress was built on Madeira at São Lourenço. This fortress and others did not prevent Madeira from briefly coming under Spanish (1580–1640) and then British control (1801-2 and 1807–14). From the last quarter of the 17th century, as the population of the Madeiras surpassed 50,000 and the islands could no longer support their own food requirements, many people emigrated even further from their ancestral roots and started a new life in Portuguese Brazil or North America. Today the island group is an autonomous region of Portugal and remains a useful stopping point in the Atlantic - nowadays for cruise ships instead of slave ships - and acts as a relay station for the Atlantic submarine cable system.