The Azores (Açores) are a North Atlantic island group, which was uninhabited before being colonized by the Portuguese from 1439. The Azores were strategically important for Portuguese mariners to use as a stepping stone to progress down the coast of West Africa and as a point of resupply for ships travelling back from the East Indies and those on their way to the Americas.

Migrants from Portugal were encouraged to settle on the various islands of the group so that wheat, vines, and sugar cane were all grown with success and exported to Europe and Africa. The Azores were jealously eyed by other European powers from the 16th century and were often the site of sea battles and land attacks, even if the Portuguese managed to always hold on to them. As Portugal developed its colony in Brazil, many inhabitants of the Azores relocated to South America, often given financial incentives to do so by the Portuguese Crown. Today, the Azores are an autonomous region of Portugal.

Geography & Climate

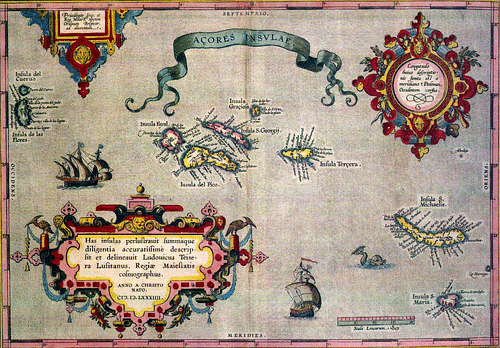

Located some 1600 kilometres (994 miles) from the coast of Portugal out in the North Atlantic, the Azores archipelago consists of nine major islands divided into three groups. The eastern group includes Santa Maria, the Formigas islets, and São Miguel with today's capital Ponta Delgada. The northern group has Flores and Corvo, while the central group has Faial, Graciosa, São Jorge, Pico, and Terceira. The islands are the tops of still-active volcanic mountains of the mid-Atlantic ridge, hence their often steep shores and mountainous interiors. Pico contains the highest peak at 2,351 metres (7,713 ft). The Azores have a subtropical climate with high humidity, making them suitable for growing various kinds of crops.

The Portuguese Empire in the Atlantic

Two captains of vessels sponsored by Prince Henry the Navigator (aka Infante Dom Henrique, 1394-1460) had landed at the Madeira archipelago in 1418 and seen the possibilities for colonization. Uninhabited, the islands were forested, had plenty of water, and benefitted from a mild climate - ideal conditions for agriculture. Settlers arrived on the islands from 1420, planting wheat with success, then sugar cane and vines. The Portuguese colonization of Madeira was just the beginning. The Portuguese Crown was keen to gain more such possessions, especially as Portugal was then a net importer of grain. The turn of the Azores began with their ‘discovery’ by Portuguese sailors in 1427 (although Corvo and Flores were not sighted until after 1450). The evidence that the Azores had been known to Europeans before 1427 is limited to a few possible inclusions on maps. Prince Henry’s captains found that these islands were uninhabited but abundant in forests with plenty of freshwaters. In addition, the total land area of the archipelago was three times that of the Madeira group.

Division of Land

The Portuguese Crown had partitioned the islands of Madeira and given out ‘captaincies’ (donatarias) as part of the system of feudalism to encourage nobles to fund the development of the islands. The Crown still retained overall ownership. This model was replicated on the Azores and elsewhere such as Portuguese Brazil. In the Azores, the process of colonization began in 1439 with overlordship divided between Prince Henry and the regent Prince Pedro, although after the latter’s death in 1449, Henry took over the whole archipelago. Not all the islands were settled at once but, over a period of the next 60 years or so, all would eventually receive settlers starting with the eastern group, then the central, and finally the northern group.

Each ‘captain’ or donatario was given the responsibility of settling and developing their area in return for financial and judicial privileges. The ‘captain’ had his own extensive estate within the territory under his jurisdiction, and he could distribute other parcels of land (semarias) to men given the responsibility to clear it and begin cultivation within a set period. Over time, these captaincies often became hereditary offices, and not all were Portuguese. The captain of Terceira, for example, was Flemish, one Jacome de Bruges.

While Portugal had free reign in the Azores in the 15th century, the Crown did squabble with Spain over possession of the Canary Islands, but the 1479-80 Treaty of Alcáçovas-Toledo set out that the latter were Spain’s domain while Portugal took the Cape Verde, Azores, and Madeira groups. There were also some additional vague clauses to the treaty that would cause trouble later such as Portugal’s right to future discoveries in Africa and Spain’s to islands beyond the Canaries, interests which were eventually identified as the Caribbean and even the Americas. Possession of the Azores certainly helped Portugal expand its empire as the islands became a very handy stepping stone to sailing down the coast of West Africa, opening up that side of the continent and ultimately exploration to the Cape of Good Hope and beyond. The Azores were especially useful on the return journey when ships were obliged to tack against the prevailing northern winds but were at least aided by the high-pressure patterns around the archipelago. The Azores also became useful for resupplying ships sailing back from the East Indies and as a stopover for the Europe-to-Americas run.

Settlement

Settlers on the Azores came from Portugal - humble farmers tired of the advantages given to large estate owners in Portugal and fishermen eager to plunder the island's opportunities for deep-sea fishing. The migrants came from all over Portugal (but particularly Lisbon and the Algarve) and Madeira. Not only Portuguese were attracted but also Spanish, Italian, French, German, and Flemish settlers, many of whom were keen to establish themselves as merchants in the archipelago. Other groups included Jews seeking greater liberty of worship and ‘undesirables’ who had fallen foul of the law in Portugal. However, the distance from Europe did mean that the Azores received far fewer migrants than Madeira.

Just as on Madeira, settlers had to clear heavily forested areas to prepare them for agriculture, and this had to be done without any indigenous population to help. They also had to deal with mountainous terrain, although São Miguel and Terceira are flatter. Other difficulties included the more or less constant westerly winds and high humidity. Travel between islands was not always straightforward, either, since the group, much further out in the Atlantic than Madeira, experienced much more dangerous seas. At least many settlers could build their homes using volcanic basalt blocks and the volcanic soil was a major benefit. European farm animals were introduced to the islands from the 1430s to provide a dependable source of meat, milk, and cheese.

As on Madeira, wheat was the first and most important crop grown with extraordinary yields possible year after year until the early 16th century when overuse of the soil began to take its toll. Vines were cultivated, cotton was grown, and yams were successfully imported and grown. Red die extracted from the resin of the dragon tree (dracacea draco) or the lichen orchil, and blue die from woad (pastel) or litmus roccella (urzela) were other highly lucrative commodities once shipped to Europe. Sugar cane was planted with partial success as the climate was not quite as beneficial for it as on, say, Madeira. In any case, agriculture generally did well across the archipelago as a whole, and by the 16th century, the problem of labour arose as farms expanded. Just as with the Madeira group, slaves were imported from West Africa to work the sugar plantations in the Azores and for use as domestic servants. From the latter part of the 17th century, tea, maize, and sweet potatoes were all grown with success.

Trade was booming both with Europe and the other Portuguese Atlantic islands (Madeira and Cape Verde). Consequently, an elite commercial class developed, particularly on Faial, São Miguel, and Terceira. Unfortunately, this elite was often more interested in the profit gained from exports than the welfare of the islanders with the unhappy consequence that there were frequent food shortages for many Azoreans while ships sailed away with full holds of foodstuffs.

Although the Azores had many positives, there was a significant threat from nature. There was a major volcanic eruption on São Miguel in 1521, which buried the then capital, Vila Franca do Campo. In 1720 Pico was devastated by an eruption. Volcanic activity has continued on several islands over the centuries, and earthquakes continue to be felt regularly today.

The remoteness of the Azores was handy for authorities to deal with political pariahs. For example, Peter II of Portugal (r. 1683-1706) took the throne and exiled his predecessor Afonso VI of Portugal (r. 1656-1683) on the islands for several years. This remoteness did not suit everyone, and many settlers, especially as populations grew on the islands into the 17th century, decided to emigrate to a new life in Brazil where the larger and more modern sugar plantations had cut in on the domination previously enjoyed by Madeira and the Azores. Indeed, the Portuguese Crown, eager to develop Brazil’s tremendous potential for agriculture, sponsored migration, especially if couples included women of childbearing age. Almost 6,000 migrants from the Azores took up residency in Santa Catarina alone. Rio Grande do Sul was another popular destination. Incentives included land, tools, draft animals, seeds, and financial help in the first two years of resettlement.

Attacks by Rival Powers

The strategic value of the Azores was much more important to Portugal than its commercial output. Angra on Terceira became a major port that welcomed and provisioned ships from around the world. The strategic value of the archipelago did not go unnoticed by other European maritime powers in the 16th century. To defend their interests, the Portuguese established a naval base at Angra and built the fortress of São Braz on the island of São Miguel in 1553. In the 17th century, the fortress of São João was constructed on Terceira. These fortresses were in response to repeated attacks by Dutch, English, and French ships from the 1530s onwards and by pirates and privateers.

In 1582-3 ships of Antonio, rival to Philip II of Spain, king of both Spain and Portugal (r. 1556-98 and 1580-98 respectively) attempted unsuccessfully to attack the Azores. These were dangerous times as the European powers now battled for control of the high seas and the riches exploited from America, Asia, and Africa. In 1592 the great treasure ship the Madre de Deus was attacked and captured near Flores. Masterminded by Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1552-1618 CE), it was the greatest ever capture by the privateers of Elizabeth I of England (r. 1558-1603 CE). Sailing from the East Indies and hoping to stop off for resupply at the Azores, the ship had 500 tons of precious cargo, which included gems, gold, silver, rolls of silk, ivory, ebony, Ming porcelain, pepper, spices, and perfumes.

The English privateers were not always so successful, as in 1591 when a Spanish fleet attacked them in the Azores and famously captured the Revenge captained by Sir Richard Grenville (1542-1591 CE). Raleigh organised another raid on the Azores in 1597, this time directly attacking Horta on Faial and causing more havoc with Portuguese shipping in the area. As a result of this attack, the São Felipe fortress (renamed São João Baptista) was built to protect Angra. Despite these threats, the Azores remained throughout a Portuguese possession.

Later History

In 1766 the system of captaincies was abolished on the islands and a single governor appointed with Angra made the capital. The wines of the islands steadily gained a reputation, especially those made on Pico whose vineyards are recognised by UNESCO. Brandy, linen, and oranges were other very successful exports from the 18th century. During the Second World War (1939-45), the continued strategic importance of the islands meant several were used as Allied airbases. Today, the Azores are a popular tourist destination for the dramatic landscape of the volcanic craters and as an excellent place to see whales.