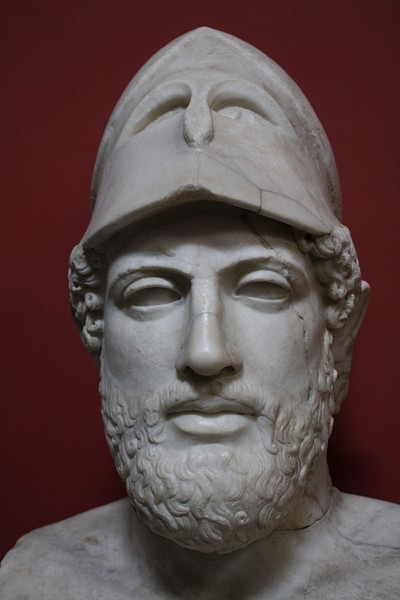

The agora of Athens developed from the 6th century BCE until it was destroyed in the Persian invasion of 480 BCE. Afterwards, the statesman Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE) used funds from the Delian League to restore it as the physical manifestation of the political power of the Athenian Empire.

The agora was first developed during the period of the Mycenaean Civilization (c. 1700 – 1100 BCE) when a fortress was built on the Acropolis and the site below, which became the agora, was used for burials. By the 6th century BCE, it was a residential area that was expanded further under the tyrant Peisistratus (d. c. 528 BCE) and his sons Hippias (r. c. 528-510 BCE) and Hipparchus (r. c. 528-514 BCE), becoming the “birthplace of democracy” after the statesman Cleisthenes (l. 6th century BCE) reformed the laws.

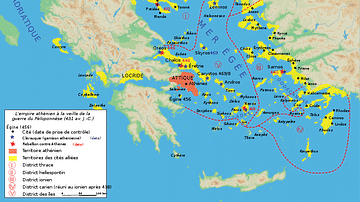

This version of the agora was destroyed in 480 BCE by the Persians, and afterwards, Pericles (l. 495-429 BCE) organized the Delian League, a confederation of Greek city-states, for defense against further Persian aggression. When these anticipated hostilities did not materialize, Pericles used the money donated by the league members to rebuild the agora and erect a temple complex on the Acropolis.

Overcoming the objections of those who viewed this as a misappropriation of funds, Pericles pushed through his agenda. The ancient agora, famous as the site of philosophical, political, and artistic advances, was made possible by Pericles’ vision which transformed a ruin into a thriving cultural center. His elevation of the city, however, was not appreciated by the other city-states, and the establishment of the Athenian Empire that rose as the city was rebuilt led to the Peloponnesian Wars (c. 460-446 BCE and 431-404 BCE). This has led some scholars to criticize Pericles’ political choices while others continue to defend them. Whichever side one aligns with, it is clear that Pericles’ restoration of the agora, and Athens generally, established the city as the premier cultural center of the ancient world.

Development Under Peisistratus

The agora was a residential district by the 6th century BCE but already regarded as an illustrious site because of its association with the Mycenaean Civilization and the great Mycenaean heroes of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Some sort of marketplace was established at the site which dealt in agricultural products from surrounding farms and other items brought up from the seaport of nearby Piraeus.

A rudimentary form of democracy was established by the lawgiver Solon (l. c. 630 - c. 560 BCE) which was overthrown by the tyrant Peisistratus. The term 'tyrant' should be understood in this case as referring to one who reigns by their own authority and their own rules. Peisistratus was not a 'tyrant' in the modern-day understanding of the term and initiated a number of important building projects, including the Panathenaic Way – the street leading from the Dipylon Gate of the city up to the Acropolis - which was already a site sacred to the goddess Athena.

Peisistratus devoted considerable attention to the agora. He found the marketplace inefficiently organized and so had it restructured for greater convenience. He had a number of wells dug to supply the area with water and financed the construction of an aqueduct as well as establishing a number of shrines and temples. When he died in c. 528 BCE, his sons Hipparchus and Hippias succeeded him and continued his policies.

Peisistratus funded his building projects with communal monies (which set the precedent Pericles would later use) and his sons did the same. Under the reign of Hipparchus and Hippias, the Altar of the Twelve Gods was erected at the agora, a monument which served as the mark by which the traveling distance to all points in Athens was measured from. The building known as the “old Bouleuterion”, a communal meeting house, was also built at this time and the boundaries of districts, including the agora, were established by the erection of boundary stones.

Hipparchus was assassinated in 514 BCE by two youths – Harmodios and Aristogeiton – who had no interest in politics and committed the murder for personal reasons and, afterwards, Hippias became more reclusive and erratic. He was finally overthrown in 510 BCE by a Spartan force the Athenians had asked for help. After the Spartans had established order and left, the Athenians rewrote their history casting Harmodios and Aristogeiton as the hero "tyrannicides" who had liberated Athens and erected a bronze statue in the agora in their honor at about the same time Cleisthenes reformed the laws and established democracy.

The Persians & the Oath of Plataea

At this point, the buildings in the agora were largely municipal with residences on the outskirts of the district. Precisely what function these buildings served is unclear, but the agora was primarily an administrative and commercial district when it was destroyed by the Persian Invasion of 480 BCE led by their king Xerxes I (r. 486-465 BCE). Xerxes I was the son and successor of Darius I (the Great, r. 522-486 BCE) who was defeated by the Greeks at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. Xerxes I’s invasion was a campaign of conquest to avenge the honor of his father.

The agora was burned along with the rest of Athens after the Greek defense of Thermopylae was broken and the Persians were free to press home their attack on their primary target, the city of Athens. The Persian forces continued their conquest until they were defeated at the Battle of Salamis in 480 BCE and then at the Battle of Plataea in 479 BCE. The Battle of Plataea, or rather a meeting allegedly held just before it, was later claimed as the reason it took the Athenians so long to rebuild the agora: because they had sworn not to.

The Oath of Plataea is an inscription in stone set up in the Attic district (deme) of Acharnae binding those who took the oath from any attempt to rebuild shrines destroyed by the Persians. To do so, it was claimed, would be to dishonor those who had lost their lives in defense of Greece. The ruins of the agora and other sites would be left as they fell as war monuments honoring the dead. Scholars have unanimously rejected the oath as authentic due to a number of factors (notably that absolutely no mention is made of the oath in any sources of the time, and none appear until after 338 BCE), but the Oath of Plataea continues to be referenced in articles as the reason the agora lay in ruins for so long from 480 to 460 BCE.

Pericles & Restoration

Actually, the claim that the Athenians were slow to rebuild the agora could be an exaggeration. The Persians were defeated in 479 BCE, the Delian League was formed in 478 BCE to defend against further aggression and, while all of this no doubt required considerable time and attention, it is probable that some attempt at restoration was made shortly after 478 BCE. Reconstruction of the agora is thought to have begun around 460 BCE but there is no way of knowing whether earlier efforts were made. The claim of c. 460 BCE is supported only by Pericles’ use of monies from the Delian League, but private benefactors could have contributed quietly on their own. It seems unlikely the city’s commercial district lay in complete ruin for 20 years.

However that may be, by c. 460 BCE, Pericles had turned the Delian League into an extension of Athenian power, and the other members were content to continue to pay dues to the league’s fund as long as Athens kept her word to protect them from others’ aggression. When Pericles began using the funds to restore Athens, the other city-states objected, claiming he was misappropriating public funds – to be used in defense of all of Greece – for a private project: the restoration and beautifying of his own city. The historian Plutarch (l. c. 45/50 - c. 120/125 CE) gives an account of Pericles’ reply:

In response, Pericles used to tell the people that, since they were defending the allies and keeping the Persians at bay, they were not accountable to them for the money; the tribute the allies paid consisted only of money - not of horses, ships, or soldiers - and money, he claimed, belongs to its recipients, not its donors, as long as the recipients provide the services for which they are being paid. (Life of Pericles, 12)

Pericles pointed out further that the tribute paid was not marked for any particular use – it was only paid in the understanding that the Athenian military would protect the other city-states – and so the funds could be used for whatever purpose seemed best. The central marketplace of the agora was renovated, enlarged, and beautified with gardens, trees, fountains, and statuary, and all of the buildings damaged in 480 BCE were restored on a grander scale with new structures built beside them. Scholar Robin Waterfield comments:

The Periclean building program included temples and other buildings elsewhere in Attica (the famous Temple of Poseidon on Cape Sounion, for example). The scale of the program as a whole, and of individual buildings, was extraordinary. The Athenian democracy left monuments of a stature normally associated with self-aggrandizing tyrants or absolute rulers…The most famous and enduring Periclean constructions, however, were religious in function and located on the Acropolis – and of these the best known is the Parthenon, the temple of the virgin goddess Athena. Work began in 447 and the bulk of the monumental temple, including the cult statue, was completed by 438. (91-92)

Pericles personally supervised some of the building projects but was the architect of the vision behind them all. He regularly inspected the work on the Acropolis a well as managing his other responsibilities as an Athenian statesman. Although restoration may have been the initial goal, the end result was complete transformation in an effort to make Athens the most impressive city in all of Greece. Waterfield notes:

One of the popular benefits of the work was, of course, that huge numbers of Athenian and foreign craftsmen were kept in state-paid employment for so long. But the main benefit was intangible: the new buildings taught Athenians to regard their city as a world leader. (91)

After the Persian Invasion of 480 BCE, the Athenian navy became the most powerful in the region and their army was equally impressive. The walls of Athens were improved and strengthened, and the entire city beautified. All of these developments went directly toward Athens becoming the superpower of the region and, since it was clearly regarded as powerful, Pericles felt it should look the part.

Buildings in the Agora

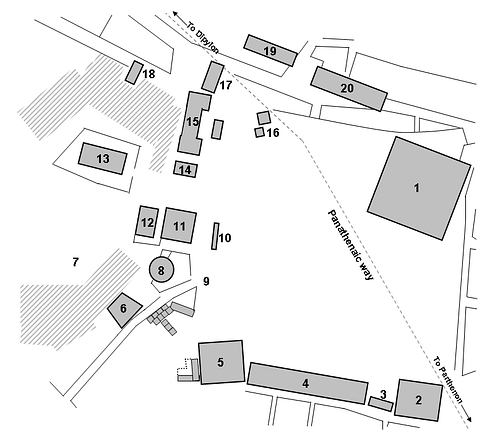

Besides fountains and restoration of shrines like the Altar of the Twelve Gods, the buildings known to have been restored or built by Pericles, or at least were part of his vision for the agora, are:

- The Poikile Stoa (19)

- The Southeast Fountain House (3)

- The Prytaneum (Tholos) (8)

- The Panathenaic Way

- The Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios (15)

- The Mint (2)

- The Dikastiria (Law Court, 1)

- The Stoa of Basileios (17)

- The New Bouleuterion (12)

- The Temple of Hephaestus (13)

- The Boundary Stones (9)

- The Marketplace

The Poikile Stoa (also known as the Painted Stoa) was a masterpiece completed by a private donation of funds from the brother-in-law of Cimon of Athens (l. c. 510-450 BCE), Pericles’ sometimes friend and other times rival. The building was a long structure with porticoes and became famous for the paintings on its walls celebrating military victories such as Marathon.

The Southeast Fountain House was a central well originally built during the reign of Hippias. It operated through a series of terracotta pipes and a pump which drew water up to a spout from which people filled their private containers. The Fountain House became a popular place for informal gatherings and gossip in the agora.

The Prytaneum (Tholos) was the seat of government but also housed the sacred fire that symbolized the life of the community. Heroes of military victories and the Olympic Games were honored at the building where the Council of Citizens also met to discuss administrative matters of the city.

The Panathenaic Way was the sacred road used during the Panathenaic Festival honoring Athena. As noted, it was built by Peisistratus but enlarged and improved upon by Pericles. It entered the agora at the northwest corner, exited at the southeast, and continued up the hill of the Acropolis to the temple complex. The Panathenaic Way still exists today and may still be walked.

The Stoa of Zeus Eleutherios was a building dedicated to the god Zeus as liberator and symbolized the freedom of the community. It was not a temple, no sacrifices were made there, but it seems to have been a communal hall.

The Mint was where the Athenians coined their currency. It was a large, square building located near the Fountain House.

The Dikastiria was the court of laws where cases were heard. It was located near the prison which was used to incarcerate short-term offenders. Although efforts have been made to associate this site with the prison in which Socrates spent his final days, nothing supports this.

The Stoa of Basileios, in the northwest corner of the agora, was where Socrates’ trial was held. The name means “royal stoa”, and it was where the Archon presided over court cases and met with his administrative council.

The New Bouleuterion (a modern-day name for the structure) replaced the old one and eventually became the meeting place for the Athenian Senate.

The Temple of Hephaestus was dedicated to the god who was the patron of craftspeople. It was begun under Pericles’ supervision c. 450 BCE and completed in 415 BCE. In the present day, it is often referred to as the Thesion because it was once thought to have been built in honor of Theseus, the legendary founder of Athens.

The Boundary Stones were the Herma (or Herms), sculptures of the god Hermes or a stack of stones with Hermes’ head or symbol at the top or simply a pile of stones understood to represent Hermes who was the patron god of travelers among his many other responsibilities. The boundary stones were first set in place under Hippias to establish the boundaries of the agora.

The Marketplace, as noted, was enlarged and beautified with fountains and gardens. It was so expansive that this market, routinely referenced as the agora, gave its name to the modern-day term for a fear of open spaces and people in them: agoraphobia.

Conclusion

The growth and enhancement of the physical city of Athens, as noted, directly correlated to its increased political and military power which finally resulted in the First Peloponnesian War (c. 460-446 BCE) with Sparta, which Pericles oversaw as commander-in-chief and which Cimon of Athens concluded in negotiating a truce. After the war, Pericles continued with his building projects and life with his consort Aspasia of Miletus (l. c. 470 – 410/400 BCE) who, according to some of his critics, wrote his famous Funeral Oration delivered in honor of the war dead.

Although he was criticized for far more serious breaches in conduct than claiming authorship of a speech, Pericles remained a popular and admirable leader until his death. Waterfield comments:

The single most important reason for Pericles’ enduring popularity was that he was the first to articulate a vision of the future towards which events of the past fifty years seemed inevitably to be driving Athens – a vision of material and cultural glory for the city, and of leadership of all Greeks everywhere. (103)

Pericles died in 429 BCE in the Plague of Athens that took many of the citizens and never saw the completion of a number of the building projects he had initiated. They were continued in his honor, however, and his vision of a city of splendor was fully realized. Even after it fell to Sparta in the Second Peloponnesian War, Pericles’ vision of the city and the reputation it enjoyed because of him enabled Athens to rise again to become one of the most important cultural and intellectual centers of the ancient world.