The life of wealthy Romans was filled with exotic luxuries such as cinnamon, myrrh, pepper, or silk acquired through long-distance international trade. Goods from the Far East arrived in Rome through two corridors – the Red Sea and the Persian Gulf. The use of different trading routes ensured a constant stream of exotic goods in the Roman Empire.

The Red Sea corridor required a trip by ship of 4,500 km (2800 mi) from India to the Red Sea port cities, followed by a caravan route of 380 km (236 mi) across the Egyptian Desert, and then another 760 km (472 mi) by ship on the Nile to the Mediterranean, for a total distance of 5,640 km (3500 mi). The Persian Gulf corridor required a trip by ship of 2,350 km (1460 mi) from India to the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers and then by caravan across the Syrian desert for 1,400 km (870 mi), for a total of 3,750 km (2330 mi). To get to India, Chinese silk had traveled another 5,000 km (3100 mi) across the rugged, mountainous terrain of Central China to the Indian Ports.

Luxury Goods

Wealthy Romans adorned themselves with cosmetics and perfumes made with cinnamon from Sri Lanka, myrrh from Somalia, and frankincense from Yemen, and they wore clothing of translucent silk from China. The streets were filled with fragrant smoke from frankincense and myrrh wafting from burners at the base of statues of the Roman emperor, and the Roman cuisine was spiced with pepper and ginger from India.

In the 2nd-century CE Roman novel, The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, a rapturous lover relates: "And now, with responsive desire waxing with mine into an equality of love, exhaling from her open mouth the odour of cinnamon, she ravished me with the nectareous touch of her tongue". During another seduction, an alluring temptress admits "The lovely face of your brother, my husband, still lingers in my eyes, the cinnamon odour of his ambrosial body still haunts my nostrils" (Apuleius, Metamorphoses 2.10).

Great braziers of incense were burned at the Colosseum in Rome to cover the stench of the blood and gore left sizzling in the hot sun. The Romans honored their deceased by burning prodigious quantities of incense at their funerals. The wealthier the dead, the more elaborate was the ceremony. Pliny reported that at the funeral of Nero’s (r. 54-68 CE) consort Poppaea, a full year’s supply of Rome’s incense was consumed; so much so that the economy of the Roman Empire was endangered.

In the cookbook of the famous Roman gourmet Apicius, pepper is included in 349 of 469 recipes. In the 1st century CE, the Roman Pliny the Elder described the allure and value of pepper as:

Why do we like it so much? Some foods attract by sweetness, some by their appearance, but neither the pod nor the berry of pepper has anything to be said for it. We only want it for its bite – and we will go to India to get it. Who was the first to try it with food? Who was so anxious to develop an appetite that hunger would not do the trick? Pepper and ginger both grow wild in their native countries, and yet we value them in terms of gold and silver. (Pliny the Elder, Natural History, LCL 370, p. 20-21)

Silk became so popular that the Roman Senate periodically issued proclamations (mostly in vain) to prohibit the wearing of silk on both economic and moral grounds. The poet Juvenal, writing around 110 CE, was appalled "by luxury loving woman who find the thinnest of thin robes too hot for them; whose delicate flesh is chafed by the finest silk tissue" (Bernstein, 2). The Roman philosopher, Seneca the Younger (3 BCE - 65 CE) complained:

I can see clothes of silk, if materials that do not hide the body, nor even one's decency, can be called clothes... Wretched flocks of maids labour so that the adulteress may be visible through her thin dress, so that her husband has no more acquaintance than any outsider or foreigner with his wife's body. (Seneca, LCL 463, 374-375)

Roman Trade through the Red Sea Corridor

Roman trade through the Red Sea corridor began in Ostia or Puteoli from which ships traveled to Alexandria and then Coptos on the Nile. It took about 20 days for the ships to reach Alexandria from Italy and another 11-12 days to move the goods down the Nile to Coptos. A cornucopia of Roman goods flowed into Coptos including sacks of gold and silver coins, fabricated tin, copper, iron, locally produced barley, wheat and sesame oil, Alexandrian glass vessels, grape juice, and wine from Italy and Syria, and purple cloth from Phoenicia. Coptos was a beehive of commercial trading and transport, and a menagerie of merchants and financiers collected there from Rome, Egypt, Arabia, and India.

The merchandise arriving at Coptos was carried overland by camel caravans to the Red Sea ports of Berenike and Myos Hormos. It took about seven days for the caravans to make their way to Myos Hormos (177 km or 110 mi) and twelve days to more southerly Berenike (370 km or 230 mi). Myos Hormos was closer to Coptos than Berenike, but the strong northerly winds of the upper Red Sea made voyages to southern African ports slower and more difficult from there, Berenike was sheltered from the high northern winds by the Ras Banas peninsula and ultimately became the premier trade emporium on the Red Sea. It remained a major trade center for almost 800 years, linking the Mediterranean basin, Near East, and Egypt with the African coast, India, China, and Southeast Asia.

Incredibly, a detailed eyewitness description of ancient travel to Africa and India has been left to us in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, written by an unknown Greek-speaking, Egyptian author in the 1st century CE. The Erythraean Sea was the ancient name for the body of water located between the Horn of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. In this remarkable account, the conditions of the routes are described, along with the emporiums and anchorages along the way, the demeanor of the locals, and the major imports and exports.

From the Red Sea ports, the Romans traveled in two directions. There was a southern African route that went down the Red Sea coast, through the Bab al Mandab Strait, and then along the eastern coast of Africa to Rhapta, close to present-day Dar-es-Salaam. The other route also went through the Red Sea and Bab al Mandab Strait but then veered east across the Indian Ocean to ports along the coast of India. They grabbed the monsoon winds across the open waters of the Indian Ocean to southwest India. There they visited ports along the Indian coast from Barbarikon, on the Indus River, Muziris (Cranganur) on the southwestern Malabar Coast, and then Sri Lanka.

The first major spice trade center in the world became Muziris, located in the Indian State of Kerala on the southwestern coast of India. The exact location is not known. Probably established by 3000 BCE, it remained one of India’s most important trading ports through the Roman period. Black pepper was the major export of this great emporium, but other trade items included locally gathered ivory and pearls, and semi-precious stones and silks from the Gangetic Valley and East Himalayan regions.

Once their ships were loaded, the traders would head back to the Egyptian ports of Myos Hormos and Berenike. There, consignments of their treasures were sent overland on camel caravans and then shipped to the commercial hub of Roman Egypt, the city of Alexandria. The diversity of the goods sent across the desert of North Africa would have been simply breathtaking – Arabian frankincense, Sri Lankan and Chinese cinnamon, Indian pepper, pearls and precious stones, Chinese silks and porcelain, African myrrh, ivory, rhinoceros horn, and tortoiseshell.

Roman Trade through the Persian Gulf Corridor

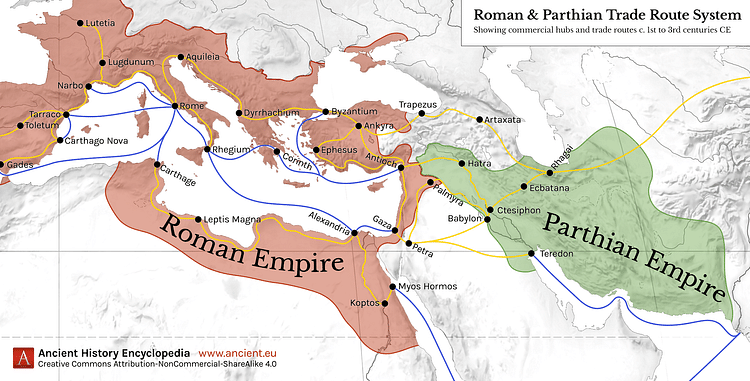

Exotic luxuries from Southeast Asia also traveled to Rome through the Persian Gulf. Silk and pepper were carried first by Indian and then by Persian sailors to the central Persian Gulf ports where they were then moved by land-based caravans north towards the Mediterranean at Antioch. Some silk and other exotic goods were also reaching central Syria via the ancient land routes of the Silk Road, but by the 1st century CE, Chinese silk was being moved to ports of the Indian subcontinent for the last leg of transport to the Mediterranean via maritime routes.

The city of Palmyra controlled most of the caravan trade through Syria to Rome. Popularly known as the "Bride of the Desert", it was founded in an oasis about halfway between the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates River. Inscriptional and archaeological evidence from the first decades of the 2nd century CE tells of the enormous range of goods that passed through the city – slaves, salt, dried foods, purple cloth, perfumes, prostitutes, silk, jade, muslin, spices, ebony, incense, ivory, precious stones, and glass.

Palmyra rose to prominence in a large part through an uneasy compromise between warring Rome and the Persian Empire. The Palmyrene traders kept politically neutral and were able to tap onto the caravan trade routes linking the eastern Mediterranean cities with the harbors of the Persian Gulf and western coast of India. They must have been masters at finding agreement as they had to deal with a diverse array of political authorities representing Rome, Parthia, the Kingdom of Kush, and the nomadic tribes of the desert.

The Palmyrenes were very hands-on in their relationships with their trading partners. They avoided using middlemen and instead established colonies at critical junctures along their extensive trade routes. There were enclaves of Palmyrene traders scattered across the far-flung corners of the ancient world from Babylon in Mesopotamia, Coptos in Egypt, and Merv on the Parthian border. Palmyrenes even sailed with their merchandise on the Red Sea.

Palmyra was made an official part of the Roman province of Syria by Emperor Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) in about 14 CE and Emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE) declared it a free city in 129 CE. During the reign of Septimius Severus (r. 193-211 CE) the city was elevated to the status of a Roman colonia, the highest civic status that could be accorded a city of the empire; in effect, its inhabitants now enjoyed full Roman citizenship status.

Which Way to Rome?

Even though the Red Sea route from Southeast Asia was much longer than the Persian Gulf corridor, it became the preferred route of the Romans for a couple of reasons. One, even though the total distance of the Red Sea – Nile route was about a third longer than the Persian Gulf – Syrian Desert alternative, it required a much shorter overland journey and therefore was cheaper. The shorter caravan distance across Egypt than Syria likely reduced cost. Second, the Romans had almost full control of the Red Sea corridor to India in the 2nd and 3rd centuries CE, while they controlled the head of the Persian Gulf for only brief periods. This meant that the goods procured by the Romans through the Persian Gulf corridor were subject to the tariffs charged by the Palmyra and Parthian middlemen.

In spite of these advantages, the Romans never stopped trading through both corridors. Maintaining two long-distance trade links buffered them against shortages caused by weather and political conditions. Due to the monsoon winds, travel across the oceans was possible only once along both routes. The Romans essentially had two seasons of delivery, a spring one in Antioch and a late summer one in Alexandria. Goods headed to the Red Sea corridor would have left India between December and January, arrived at the Red Sea in February, and got to Alexandria in August. Goods traveling through the Persian Gulf corridor would have left India for the Gulf in November, arrived there between January and February, and made their way to Antioch between April and May. The use a network of trade consisting of multiple routes ensured that the Roman markets would receive Indian Ocean imports at different times of the year and from multiple sources.