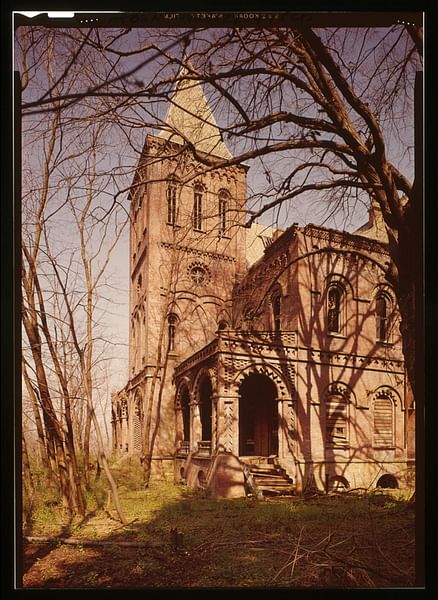

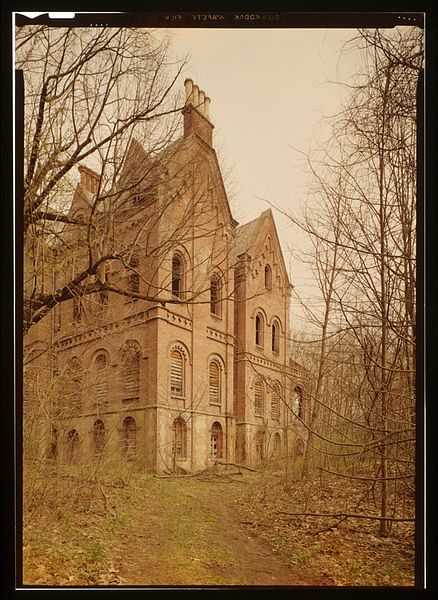

There are many fascinating and forlorn ruins throughout New York’s Hudson Valley, and, among them, the tottering remains of what was once considered the grandest home in the area and among the most famous in the country: Wyndclyffe. Between its construction in 1853 and its decline after 1876, it was a symbol of wealth and power.

Wyndclyffe was the home of the millionaire spinster Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones (l. 1810-1876), who was the aunt of writer Edith Wharton (l. 1862-1937). Best known for her novels The Age of Innocence, The House of Mirth, and Ethan Frome, Wharton visited the house as a child and hated it, calling it intolerably ugly, but she seems to have been in the minority opinion.

Although the house is a ruin today, considered far too unstable to save, it was once the site of grand parties overlooking the majestic Hudson River where men and women of the Gilded Age strolled across the rolling lawns and took tea in the ornate sitting rooms whose windows looked out upon carefully manicured grounds.

The house, like all of the great mansions of the Gilded Age, exemplified the custom of wealthy Americans creating an artificial landscape around a central house from which nature could be appreciated without having to bother with the various pests and threats of the natural world, a custom that scholar Harvey K. Flad as termed the "parlor in the wilderness". Jones’ estate is said to have been so elaborately ornamented, both the house and grounds, that it gave rise to the expression “keeping up with the Joneses”, a reference to one’s attempts at matching a neighbor’s displays of affluence with one’s own.

The house and lands were left to Jones’ nephew and sold in 1886. They then went through a number of owners over the next 60 or so years as the house declined. The lands were steadily sold off and the house became too expensive to maintain. It was abandoned in 1950 and began the slow decline and collapse that leaves it in ruins today.

The Gilded Age & Parlor in the Wilderness

The American author Mark Twain (l. 1835-1910) coined the phrase 'the Gilded Age', which refers to the period between c. 1870-1917 in America. He intended it as a negative commentary on an era which glittered on the surface but was corrupt beneath owing to the greed of robber barons who engaged in unscrupulous business practices to increase their wealth at the expense of the common good. Today, however, the phrase is generally understood in a positive light with reference to a transformative time in America's history when urbanization and industrialization increased rapidly and the United States entered the modern age or, more commonly, to the age of the great estates and wealthy American aristocracy prior to the implementation of income tax in 1913 and America's involvement in WWI in 1917, which led to the War Revenue Act that further taxed the rich.

This period saw extensive development of towns and cities throughout the regions that were not still held by Native Americans, including the city of Manhattan. As one of the greatest centers of industry and commerce, Manhattan was home to some of the wealthiest families in the country but, as it developed further, and became more crowded, the rich established second homes to the north in the Hudson River Valley. The region was already known to the upper class who began establishing estates there in the 18th century, but in the 19th, these large manors proliferated, as did grand hotels to accommodate guests visiting them, spas, and other industries. The concept of 'getting out to the country' became associated with one’s health and some of the wealthy who visited the Hudson Valley for that purpose eventually built homes there. Flad comments:

"Taking the waters", breathing pure air, or even drinking fresh milk offered acceptable reasons for Americans to travel, especially those who lived in cramped, smoke-filled, dirty cities, and travel for edification and refinement in taste could be justified as morally acceptable. The fact that such recreational activities might also assist in one’s climb upward in the social hierarchy eventually became reason enough to travel to resorts. They were public spaces where private acts could be less restrained and where lives might be transformed. (359)

These spas and resorts, with their ornate buildings and carefully manicured grounds, became what Flad refers to as the embodiment of the "parlor in the wilderness", but these places were not to everyone’s tastes and, even if they were, one still needed to display one’s wealth and status through one’s own home and grounds. Creating one’s own "parlor in the wilderness" not only provided a family with a comfortable home but became a mark of one’s social standing and the grander the estate, the higher one was understood to sit in the hierarchy. In the high society of Manhattan in the early 19th century, one would have a grand home built in the city, where everyone else would have to pass by and acknowledge it, but in 1853 Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones broke with that tradition and built her home two hours by train to the north, on 80 acres of land overlooking the Hudson River, and forced the rest of society to follow her lead.

Wyndclyffe & High Society

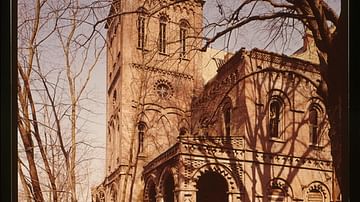

Jones selected a wilderness near the hamlet of Rhinecliff to build the grandest of all summer homes. She purchased the 80 acres (32 ha) of land from a Mr. Jacob Cramer and hired the local architect George Veitch to design the house. Veitch was well known for his work on the nearby Russell Estate whose parameters today define the boundaries of Rhinecliff (though the estate itself is long gone) and whose work may still be seen in such structures as the Rhinecliff Hotel and the Episcopal Church of the Messiah in nearby Rhinebeck.

Veitch designed a three-story Hudson River Gothic mansion in the Norman style, which consisted of 24 rooms, a carriage house, boathouse, and dock, all set grandly on a hill of terraced lawns overlooking the river. Miss Jones had her house so opulently furnished, her grounds so well sculpted, that other wealthy families in the area added adornments and extravagances to their own summer homes to keep pace with her; this practice gave birth to the famous idiom regarding trying to match the lifestyle of one's neighbors: "keeping up with the Joneses". The house dominated the landscape and every innovation and ornamentation to the building and grounds was utilized to impress and were intended specifically for those of Jones’ social circle who attended gatherings there.

Parties held at Wyndclyffe, as at other estates, were as much political maneuvers and matchmaking between families as social events. Young women were expected to "come out" at such events, meaning they were presented to society as eligible for marriage, after which they would take their place in the hierarchy. Flad describes how an estate gathering worked:

The buildings and the carefully landscaped grounds became a parlor in the wilderness. Women dominated the veranda as social space. Though a symbol of middle-class domesticity in the wilderness, it was public rather than private space, where competition for class status acted out. Rituals of courtship were performed under the watchful eyes of family members. (359)

There are no accounts of how the parties at Wyndclyffe were conducted specifically, but it is assumed they followed the custom as described in detail at other estates and, possibly, as recounted by Edith Wharton in works such as The House of Mirth and The Age of Innocence. Wharton describes her own experience of "coming out" in her autobiography, A Backward Glance:

When I was seventeen, my parents decided that I spent too much time in reading, and that I was to come out a year before the accepted age. The New York mothers of that day usually gave a series of "coming out" entertainments for debutante daughters, leading off with a huge tea and an expensive ball. My mother thought this absurd [and that it would be] easy enough to launch me in [an] informal way [through just a ball]. I was therefore put into a low-necked bodice of pale green brocade, above a white muslin skirt ruffled with rows and rows of Valenciennes, my hair was piled up on top of my head, some friend of the family sent me a large bouquet of lilies-of-the-valley, and thus adorned, I was taken by my parents to a ball…To me, the evening was a long, cold agony of shyness. (77-78)

Estates like Wyndclyffe were not just playgrounds for the wealthy, however. Jones was a cousin of the immensely rich Astor family, who built an estate of their own nearby in the Village of Rhinebeck (known as Ferncliff), and others soon followed their examples. Wyndclyffe, like many of the homes of the wealthy in the Hudson Valley, was built as a weekend and summer home for Miss Jones as an escape from the urban environment of New York City. The other palatial estates that grew up in its shadow were likewise second homes, but all of these required caretakers, grooms for the horses, gardeners, cooks, servants, farmhands, and a host of others to care for them whether the family was in residence or at one of their other homes. Estates like Wyndclyffe provided the people of the community with jobs, fueled the economy, encouraged building projects, and boosted local industries.

Wharton on Wyndclyffe

The Gilded Age estates of Staatsburg, New York, south of Wyndclyffe, belonging to the Mills, the Huntingtons, and Hoyts all sustained the community there as well as the surrounding towns and villages. Edith Wharton was frequently a guest at the Mills Mansion (known as Staatsburgh), which is thought to be the model for Bellomont in her novel The House of Mirth. Bellomont is described as a pretty house but the author had nothing good to say about Wyndclyffe.

Wharton often visited her aunt’s house when she was young and describes it unflatteringly as the most repulsive place of her childhood. She refers to the house as 'Rhinecliff' the one time she mentions it in her memoirs:

The effect of terror produced by the house at Rhinecliff was no doubt due to what seemed to me its intolerable ugliness. My visual sensibility must always have been too keen for middling pleasures; my photographic memory of rooms and houses – even those seen but briefly, or at long intervals – was from my earliest years a source of inarticulate misery, for I was always vaguely frightened by ugliness. I can still remember hating everything at Rhinecliff, which, as I saw, on rediscovering it some years later, was an expensive but dour specimen of the Hudson River Gothic; and from the first I was obscurely conscious of a queer resemblance between the granitic exterior of Aunt Elizabeth and her grimly comfortable home, between her battlemented caps and the turrets of Rhinecliff. (28)

Wharton’s use of 'Rhinecliff' in referencing the house seems to have given rise to the belief that the hamlet of Rhinecliff came to be named for Jones’ home. Actually, the Jones' estate was known as Wyndclyffe as early as 1859, and there is no evidence to suggest the house was ever formally known as 'Rhinecliff' and so had nothing to do with the name of the town. Most likely, Wharton referred to her aunt's home as 'Rhinecliff' in the same way the Mills family referred to their country home as 'Staatsburgh' simply by using the locale as the name of the estate informally.

Death & Decline

Elizabeth Schermerhorn Jones died in 1876 and left the estate to her nephew Edward Jones, Jr. who continued to care for the property until he sold it to Mr. Andrew Finck in 1886 for $25,000.00. Mr. Finck renamed the estate Linden Grove, and it remained in the Finck family, with one member selling it to another over the years for the token sum of one dollar until it was sold in 1934 to one Anna Rice for $1,800.00.

It is alleged that, under the Rice ownership, the house and grounds became a nudist colony in the mid-'30s. Anna Rice kept the house only two years before she sold it, possibly owing to the expense of upkeep or perhaps owing to the unpopularity of the nudist colony, to a family named Lesavoy for $100.00 (the Lesavoy's have also been cited as proprietors of a nudist colony on the grounds). After that, ownership becomes less clear as do the reasons for sale and purchase price. It was again sold in 1961 for $12,500.00 and then in 1971 for $85,000.00.

By this time, the once-grand 80 acres by the Hudson River had been subdivided and sold off so the house now sat upon a meager 2.5-acre (1 ha) lot. None of the owners, after the Finck family, appear to have actually lived in the house or cared for it very much, and gradually, it fell into ruin.

Conclusion

Although the house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, no preservation efforts have been made to restore it, and even though it was purchased again in 2003, allegedly with an eye toward restoration, nothing has been done to stop time from pressing the former jewel of Hudson Valley Estates into the earth.

Many once-grand homes of The Gilded Age have been preserved and are still flourishing today. One famous example of this is Oheka Castle, built between 1914-1919 by financier Otto Hermann Khan in Huntington, NY, now a hotel, and another, previously mentioned, is the Mills Estate, built in 1895, which is today a State Historic Site and park. Wyndclyffe, unfortunately, did not weather the years well enough to follow these examples.

Today the house is a precarious wreck, plastered with 'No Trespassing' signs and regularly monitored by the local police who chase would-be ghost hunters, relic collectors, and the occasional history enthusiast off the grounds. Still beautiful in ruin, Wyndclyffe's fate seems sealed as it has passed beyond the point of restoration. Even so, in its day, it was the envy of the very rich of the Gilded Age, a home visited by political, financial, and literary luminaries, and its weathered brick and empty windows still have much to say to the attentive visitor.